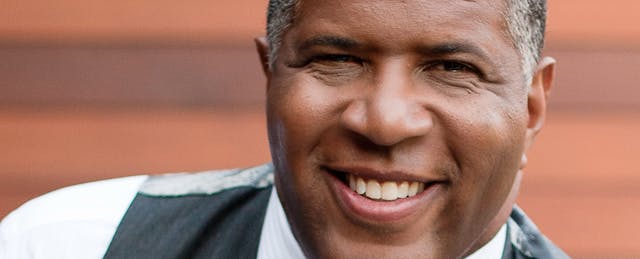

In September 2019, Vista Equity Partners CEO Robert F. Smith followed through on his pledge, paying $34 million to settle the loan debt for the nearly 400 students who graduated that spring from Morehouse College. Morehouse President David A. Thomas praised it as a “liberation gift” for those graduates as they start their careers without debt.

But what about other students?

While generous, Smith’s largesse was just a band-aid on the country’s $1.6-trillion student debt problem, the solution to which shouldn’t hinge on one’s luck of timing, says Keith B. Shoates, vice president of the office of the CEO at Vista Equity Partners. “That was a transformational gift. But it doesn’t scale. It was for one institution, for one class of students.”

Smith, the wealthiest Black person in America according to Forbes, has pledged to reduce student debt, particularly at historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) where students graduate with a median debt of $29,000, or about 32 percent more than their peers from other institutions.

This summer, Smith helped set up the Student Freedom Initiative (SFI), a nonprofit that aims to provide financial and career support for HBCU students. And last week, it announced the first nine colleges that will be part of the program: Claflin University, Clark Atlanta University, Florida A&M University, Hampton University, Morehouse College, Prairie View A&M University, Tougaloo College, Tuskegee University, and Xavier University of Louisiana.

SFI is funded by a pair of $50 million contributions—one from Smith personally, and another from the Fund II Foundation, where Smith also serves as board president. (Smith has also admitted to tax evasion to federal authorities and paid a fine, but has not been criminally charged.)

Starting in fall 2021, the SFI program aims to serve 900 juniors and seniors who are pursuing STEM majors, says Shoates, who is also executive director of SFI. (Here are the approved programs at the nine schools.) The plan is to eventually scale that number to support 5,000 students each year across all participating colleges.

An anchor part of the program is a financing vehicle that SFI officials believe can help alleviate college debt at HBCUs. Called an “income-contingent financing alternative,” it allows rising juniors and seniors to borrow up to $20,000 per year after they’ve exhausted federal subsidized and unsubsidized loans, grants and other scholarships offered by their colleges.

Some of the repayment terms are similar to those found in income-share agreements (ISA). For every $10,000 a student takes out, they agree to pay 2.5 percent of their salary every month for a set time after they get a job, as long as they are earning at least $30,000. (So if they take out the full amount available—$40,000—the monthly payment would be 10 percent of their income.) All repayments go back into the SFI fund to support future students, with the goal of making this a self-sustaining fund.

But unlike ISAs that set the repayment cap as a multiple on the amount borrowed (the University of Utah is set at 2X, for example), SFI pegs its cap to be lower than what a student would repay if he or she borrowed the same amount under a Parent PLUS loan.

For example, a student taking out a $10,000 Parent PLUS loan would end up paying back about $12,904.80 over a 10-year period (or $107.54 a month), at the current 5.3 percent interest rate. Borrowing that same amount under SFI, if the student’s income-based repayments are $107.54 per month, he or she would complete the repayment obligation in a shorter period of time, and end up paying less in total over the same 10-year period.

“Our pricing is such that the terms will be better than taking out a Parent PLUS loan,” says Fred Goldberg, a former IRS commissioner who is now an outside counsel for the Student Freedom Initiative. He says the financial modeling is based on “conservative” assumptions, including a reduction of salary projections to account for the pandemic’s impact on jobs and wages.

That modeling was done in partnership with the Jain Family Institute, a New York-based nonprofit that has helped other programs, including Purdue University and the San Diego Workforce Partnership, research and design their ISA terms.

Beating Parent PLUS

When it comes to student financing options, Parent PLUS loans are generally considered one of the last resorts after students hit their federal loan limit (typically $5,000 to $7,500 each year). As the name implies, this option lets parents borrow money to fund their child’s college education, but on terms that are less favorable than federal loans. Interest rates are higher, and interest accrues as soon as the loan is taken out, not after a student graduates.

Families can borrow more under a Parent PLUS loan, but critics say this has compounded the debt problem. A report from the College Board found that the average Parent PLUS loan was $17,220 for the 2018-19 school year, or 2.6 times the average undergraduate student loan. Roughly 3.6 million families now hold over $100 billion in Parent PLUS debt, according to the National Student Loan Data System—and it is estimated that more than 1 in 8 will default.

Shouldering a disproportionate part of that debt are HBCU families. A report from the United Negro College Fund found that nearly twice as many HBCU undergraduates rely on Parent PLUS than their non-HBCU peers. A 2019 analysis by USA Today found that the percentage of families with Parent PLUS loans at HBCUs is twice that at all colleges combined, despite the fact that over 40 percent of Black families with such loans earn less than $30,000 a year.

“Each year, thousands of black graduates from HBCUs across America enter the workforce with a crushing debt burden that stunts future decisions and prevents opportunities and choices,” Smith said in a statement. “The [Student Freedom] Initiative is purposefully built to redress historic economic and social inequities and to offer a sustainable, scalable platform to invest in the education of future Black leaders.”

Besides promising a lower overall cost versus Parent PLUS loans, SFI’s repayment terms and protections could also make it attractive for students and families, says Kevin James, CEO of Better Future Forward, a nonprofit that partners with college readiness programs to provide ISAs for students attending college.

Under a SFI, monthly payments don’t start unless one starts earning above $30,000, and payment obligations end upon bankruptcy, permanent disability or death, or after 20 years. Students can also defer up to 12 monthly payments for any reason.

“As people look at these options, I think the income-based protections are the most important aspect, not whether one beats the other to a slight degree in terms of cost,” says James.

More Than an ISA?

Today, more than 50 U.S. colleges offer income-share agreements to students. Most recently, Robert Morris University announced its students can take out up to $5,000 per year through its “Colonial Success Fund” ISA program.

Although SFI’s financing terms have similar repayment terms as most ISAs, Shoates prefers not to use that term. That’s because, he says, students who receive the funds are also eligible for other services, including technology and career development opportunities offered by SFI partners. They include companies in The Business Roundtable, an association of corporate executives, that have pledged to provide internship opportunities and discounted laptops and other devices to students. Others have committed to giving technology infrastructure support services to the schools that are part of the network.

The long-term goal, Shoates adds, is to extend the financial terms and other benefits across all colleges in the SFI network—not just HBCUs, but also other minority-serving institutions that could be part of the program in the future.

Providing student support services is critical to making any income-based repayment tool work, says James. Since fall 2017, Better Future Forward has provided ISAs to 162 college students who also participate in regional college-readiness programs, like One Million Degrees and College Possible, that provide mentoring and coaching services. About 90 percent of recipients are still in school or have graduated.

“These programs have to be powered by student outcomes and their ability to successfully transition into jobs,” says James. “Funding is not the only source of challenge, and we have to think about more than just money.”

Editor’s note: This piece has been updated to note Robert Smith’s admission of tax fraud charges to federal authorities.