Here’s what Margery Mayer, president of Scholastic Education, had to say.

You are required to spend the next year of your life in either the past or the future. What year would you travel to and why?

My first thought was to go back to 1968 to join the crowd at Woodstock and spend a year following the Grateful Dead. Certainly one could make a strong case for the educational value of being at the epicenter of societal revolution. But then I realized that maybe I had been there and, a la Timothy Leary, simply didn’t remember it. And what you can’t remember, you haven’t learned. Ergo not very educational.

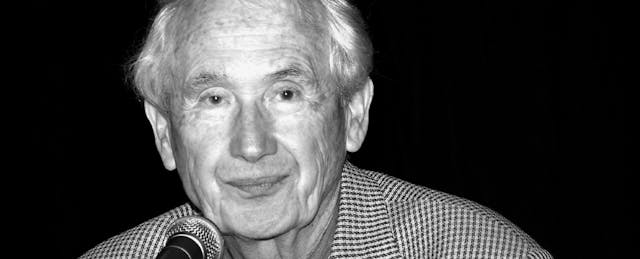

But then I had a much better idea. It’s still 1968, but now I’m the fortunate student of a truly great teacher. I’m a 10th grade student of Frank McCourt, who taught for 30 years in the New York City schools before the world came to know him as the author of Angela’s Ashes.

You can read McCourt’s account of his years teaching in his wise and entertaining memoir Teacher Man. It’s a case study in what makes a great teacher. It’s not about teaching for the test. In fact, McCourt admits to grading essays for state tests with a large dose of generosity to boost pass rates. And it’s not about following the rulebook for classroom management as handed down by the higher ups.

What it is about is telling stories and listening to stories: his stories and the stories of his students.

For example, while teaching at a technical high school, he realizes that everyone needs an excuse note at one time or another and so he asks his class to write a note from Eve to God. One student writing as Eve says that she’s tired of God sticking his nose into her business. She goes on to write that God could go and hide behind a cloud somewhere if he didn’t like what she and Adam were up to. More excuse notes followed: Judas, Attila the Hun, Al Capone. McCourt had to make his students leave long after the bell rang. I want to be in that class.

Here’s a reading lesson. McCourt tells his class that he’s going to recite his favorite poem. The class groans, he tells them to piss off and recites the nursery rhyme “Little Bo Peep.” By now he’s teaching at the highly selective Stuyvesant High School. His college-bound students ask him if he’s joking. That launches a close reading. Based on textual evidence, the class determines that Bo Peep is cool and that she believes in her sheep, which in turn leads to the conclusion that the poem is about trust and giving each other space. I want to be in that class.

McCourt wrote, “Instead of teaching, I told stories.” I had the privilege of sitting next to him at a couple of Scholastic-sponsored events and I remember his stories vividly. He was a storytelling machine of heart and wit. Just think of the education he brought to 4,500 or so incredibly blessed New York City high-schoolers during his teaching career. If only I could go back to be one of them. Now that would be a lot more exciting than Woodstock.