In the world we live in, unprecedented opportunities to learn co-exist with enormous inequality. Today there are over 100 million more children enrolled in primary schools than a decade ago, and early childhood education is skyrocketing--a fantastic outcome in such a short period of time. Yet there are also an estimated 250 million children who still cannot adequately read, write and count and 57 million who are still not in school.

The key reason is cost. A recent UNESCO study estimates that the total cost of educating all children at pre-primary, primary and early secondary levels reached $100 billion in 2012, and will continue to rise. The concatenation of more children achieving higher levels of education within dramatically expanding K-12 populations across Asia, Latin America and Africa is unleashing immense pressures between affordability, fiscal budgets and educational supply on one hand, and the attainment of higher learning and employment expectations on the other. In Africa alone, a projected college enrolment rate increase of 7 to 30 per cent over the next twenty years is going to require governments to spend 50 times the current level of $1 billion per year spent across the entire continent.

There are two fundamental ways to tackle these challenges: either lower the cost of education (while hopefully retaining quality and equity) or get someone else to pay for it. For basic education, the primary sources of funding continue to be domestic country budgets, multilateral and country-specific aid programs (like the World Bank, UNESCO’s Capacity Development for for Education for All Programme, and USAID), and overseas remittances. Yet in the face of bulging education demographics and funding costs, this is not enough. The private sector--specifically, the edtech community--must fill the gap. Here are a few ways this is happening.

Seed and Venture Funding for Low-Cost Schools and Services

Venture and seed funding offer a lifeline to education entrepreneurs, who often have no access to traditional forms of bank lending, in an education industry which has little experience with private sector involvement. Not surprisingly, the most ambitious education start-ups in developing countries are now getting funded through venture capital.

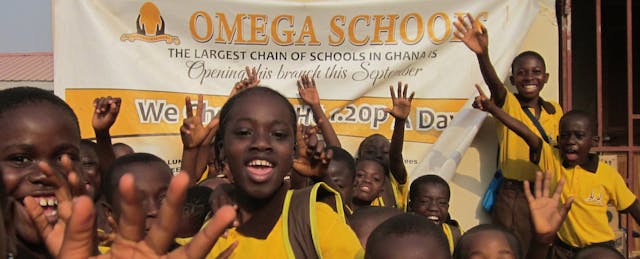

For example, Pearson's Affordable Learning Fund (PALF) and a number of affiliates have sparked investments into low-cost school chains including Sudiska pre-schools in India, APEC middle schools in metro Manila, Omega Schools in Ghana, and Bridge Academies in Kenya. These are for-profit, scalable schools charging as little as $3 a month to families and harnessing technology to deliver curriculum and centralize management costs.

Their level of ambition is wild: Bridge, with a recent investment boost from Mark Zuckerberg, is targeting a 100-fold expansion from its current 100,000+ students, to 10 million by 2025. Still, the capital in play is miniscule compared to the massive unmet demand in parts of Africa and South Asia. PALF has only $50 million to manage, and others such as Unitas Seed Fund in Bangalore are approaching $20 million. Larger, follow-on investments to develop a global network of "academies in a box"--and the edtech innovations to power them--are only beginning to make a difference.

Alternative Loan Finance and Repayment Methods

Global emerging markets are now facing higher borrowing costs on the back of rising interest rates. This is bad news for students in countries that lack an institutional lending capacity for education. The traditional use of tuition discounts, subsidies and financial aid will help only at the margins, bringing the question of how student loans are accessed and structured to the open market.

Consider a recent IFC sponsored study of 70 alternative finance companies and the range of financial innovations on offer. Included are Ideal Invest, which uses asset-backed securities and big data scoring to fund low-cost and low interest loans in Brazil, and Eduloan, which uses innovative screening and risk-management methods to reach middle-income borrowers in South Africa. Still others are more efficiently matching loan profiles to employment prospects, creating job-related payback schemes, and creatively working with education-related microfinance.

Peer-to-Peer Lending and Crowdfunding

The popularity of US-based ”P2PL,” or peer-to-peer lending (in which technology allows the matching of individual lenders with borrowers outside of traditional intermediaries such as banks), and student finance management platforms such as SoFi, Prosper and CommonBond; DonorChoose for teachers’ projects; and peerTransfer for internationally mobile students, has quickly spread around the world. Not surprisingly, Asia is now the second largest region for crowdfunding, growing 320% last year to $3.4 billion raised, at double the estimated rate of the US in 2015. Companies such as microcredit P2P platform CreditEase in China and FairCent in India are offering vast potential for student finance needs and a way around traditional banking systems.

Business Activism and Investment

Multinationals have long complained about talent gaps across emerging economies. Yet a recent survey showed that while $20 billion per year was spent on corporate social responsibility (CSR) by Global Fortune 500 companies, only $2.6 billion, or 13%, was education-related. There are exceptions--IBM spends an estimated 72% of its CSR budget on education--and large-scale initiatives such as CISCO's Networking Academy or Santander Universities (the education division of Banco Santander) are delivering education investment and innovation to hundreds of thousands of students.

But for many companies operating globally, education is still viewed as a "social responsibility" rather than a commercial imperative. Businesses may recognize that the process of educating, securing and retaining talent is the best way to build sustainable profits and shareholder value—but they must do something about it while their future employees are still students.

With the world now in reach of educating every child, pressures related to the funding and cost of education are, paradoxically, going to intensify. In the years ahead, more primary school graduates will create higher demand for secondary and university education and, in turn, a deeper pool of potential workers in search of employable skills. This dynamic calls on private companies to provide the type of innovative technology, funding, and market-driven growth solutions that have already shown so much promise, but which will require even more attention to those populations who need it most.