Across the country, schools want students to focus more on learning concrete skills than abstract concepts. This approach often goes by the name of “competency-based learning,” which emphasizes skill proficiency over grades. (That C+ in Algebra, for instance, doesn’t say much about a student’s grasp of math.)

Educators believe competency-based instruction works best when students have the freedom to drive their own learning. But tracking their progress in a flexible learning environment, where every kid may be on a different learning path, is extremely challenging. Traditional learning management tools and gradebooks are not set up to support these structures.

One school in Philadelphia decided to build its own software to support its student-driven, competency-based pedagogy. Fed up with existing learning platforms, administrators at Science Leadership Academy (SLA) developed Slate, an open-source platform that can be customized depending on what a school needs. (Here's the code repository on GitHub.) The tool is now used in U School, the Philadelphia School, Matchbook Learning schools, and more—and it’s a testament to how homegrown tools can sometimes serve schools better than existing options in the market.

The History of Slate

Science Leadership Academy (SLA), a public magnet school in Philadelphia, was founded in 2006 around the idea that high-quality project-based learning (PBL) best prepares students for the real-world. Its mission statement champions the use of PBL to instill “core values of inquiry, research, collaboration, presentation and reflection are emphasized in all classes.” Every student is equipped with a laptop. But in early 2010, principal Chris Lehmann grew frustrated from looking for digital tools that can support his school’s project-based approach. “We wanted an SIS (Student Information System) that would match and enhance our vision for school," he recalls.

Later that year, Lehmann asked the school’s technology department head, Chris Alfano, to build a multi-faceted learning management system-student information system combo that supports communications between teachers, students and parents, and store school records and assignments. Thus, Alfano put together a general open-source platform—Slate—that schools could customize and adapt based on their needs. For SLA, Slate incorporated existing tools teachers were using, including Google apps, and allowed them to organize those resources on a student platform.

Slate was tested in SLA throughout 2012. Word got out, and by 2013 three dozen schools across the country were clamoring to try it out. To support demand and continue to grow, Alfano and a friend, John Fazio, decided to migrate the Slate product to an independent web software engineering firm they’d been operating, called Jarvus Innovations. "We were running Jarvus full-time before Chris [Alfano] joined SLA. Chris joined SLA as a part time position after he heard Lehman talk at Ignite Philly and fell in love with his vision for the future of edtech," Christian Kunkel, Jarvus's Director of Educational Technology, reports.

Alfano left SLA to work on Slate and Jarvus full-time. "Alfano, Lehman, and Fazio decided that the best opportunity to support its growth and sustainability was to let the Jarvus’ team of engineers take it to the next level," Kunkel reports.

How B-21 Integrates Slate to Support Competency-Based Instruction

One of the first places to integrate Slate is Building 21 (B21), a cluster of two high schools within the “Innovative Schools Network” in the Philadelphia Public School District. Founded in 2012, B21 serves 450 students in Philadelphia and nearby Allentown, all of whom are entrusted with a high degree of autonomy over their learning. “B-21 is a competency-based school, done through project-based learning with the help of technology," explains Thomas Gaffey, B21’s Chief Instructional Technology and a former teacher. “We want the work that students do now to have impact.”

At B21, workshops and studio projects take the place of traditional classes and grades, which makes having the right learning management tool critical to keeping track of students’ progress. In the early months of the 2013-2014 school year, Gaffey searched for a tool that can be customized for his school’s needs. He heard from friends that “Slate is very good at building custom tools very quickly, with great aesthetics. After meeting them, we found our values aligned very closely.”

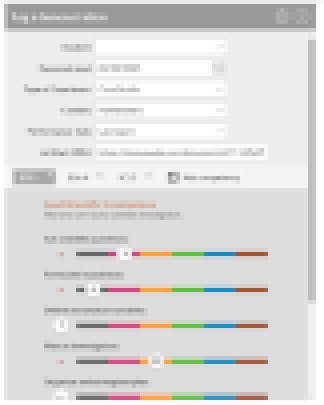

Gaffey worked with Jarvus to create a version of Slate that allows students to complete “studio” projects and track the competencies that those projects hit upon. Teachers have access to their own dashboard that acts as a progress monitoring tool and a competency-based gradebook. For example, let's say that a science teacher is leading a "Mythbusters" project, where students have to lead a scientific investigation. A teacher can "log a demonstration" (see picture below), and define a task that has multiple competencies in the same content area as well as different content areas.

The colors you see represent the different levels of competencies, and the student gets assessed on those competencies. For example, "8" is the equivalent of 8th grade and "13" is first year of college. So, in retrospect, a student could be performing at a 9th grade level in one competency, and lower or higher in another.

As demonstrations get logged, the main teacher dashboard gets updated (see below). Competencies are listed on the left and students (names blurred out) are listed across the top. Each progress bar represents a completion percentage of tasks completed on grade level. When you see a red boxed number, that means that the current performance level falls below the threshold for credit.

See "Writing Evidence-based arguments," for example, down below? The first student shown has currently completed 69% of yearly tasks, and appears to be performing at a 9th grade level or above. But the student over to the right? Sure, he/she has completed 100% of tasks, but at an 8.31 level--significantly below grade level, but without the pesky A through F grade system.

Even more helpful, the teacher can expand individual competencies to see where a student is performing well, and where tasks are missing or not yet complete (see below). And if a student isn't performing well, those low-scoring tasks can be redone and then re-updated.

Are you wondering about the student side? Below is screenshot of the student dashboard. Here's where the student autonomy piece comes into play: students are alerted as to their progress on a daily basis. As they turn in parts of projects over Google docs, which is integrated into Slate, they see how their progress tracks on their competencies. Below is a student's performance on a competency that was delivered through a recent "Narrative Writing" task. This student is performing at level 9--well done! But if they aren't, there's opportunity to redeem oneself.

What Other Schools and Districts Can Learn From This

As school leaders rethink concepts of space, time and instructional approaches, it is often the educators who have the keenest sense of the types of tools needed to support new—and sometimes unproven—school models.

There’s a growing precedence for schools creating their own tools and spinning them off into independent businesses. Data visualization platform Schoolzilla came out of Aspire Public Schools. Classroom feedback system ExitTicket came out of Leadership Public Schools. And Summit Public Schools, a California-based charter network, built its own Personalized Learning Plan (PLP) software with the help of engineers from Facebook, and is already sharing the tool through its Basecamp program.

Slate is open source, meaning that it can be freely used, changed, and shared. According to Christian Kunkel, the software is "free to use on your own hardware... We help pioneering schools and networks build tools that facilitate their innovative learning models, similar to the agreement with Building21 and the Competency Tracker."

Matchbook Learning, which works to turn around schools in Michigan and New Jersey, white labels the tool under the name “Spark,” for example. The price varies per school and district, but when asked how much B21 is paying, Gaffey is more excited to share an extra bit of information: “We paid $30k. But when that money ran out, [Jarvus] kept working on the project,” Gaffey explains, adding “They are dedicated to the project because of our vision.”

"Slate supports itself financially by selling hosting and management services of those tools on our own hand-built infrastructure," Kunkel adds.

“When I asked one of Slate's founders whether he was concerned about competitors stealing, replicating and potentially re-selling aspects of Slate's platform for profit, I loved his response. He said that if it helps kids learn, then we're ok with that,” shares Sajan George, founder and CEO of Matchbook Learning.

Educators like Gaffey see Slate as more than just another tool that organizes and keeps track of students’ work. “Our end game isn’t just integration—it’s to give kids control through the platform.”