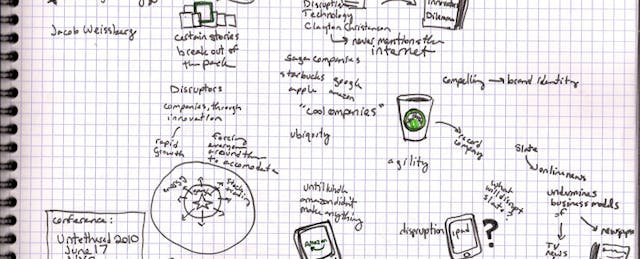

It was nearly two years ago that Clayton Christensen, the Harvard Business School Professor and authority on disruptive innovation, announced that higher education would be the next industry disrupted by technology and the Internet. Since then, we have seen the rise of the MOOC, which has presented an alternative model of higher education that could very well represent the future of how we educate our workforce.

Given the massive disruption of the publishing world over the last decade, the evolution of journalism can give us some real hints about the robustness of MOOCs and where higher education may be headed in the next decade.

“Those Who Cannot Remember the Past…”

For those that have followed journalism and publishing, it's easy to see the parallels.

An industry is transformed with technology that eliminates the primary barriers to entry: the costs of creating and distributing content. Millions of competitors, many willing to work for free or unlivable wages, enter the fray. The incumbent companies and institutions try every option, but end up contracting to a fraction of their size, leaving just a few survivors to split a much, much smaller pie.

Of course, the creative destruction of journalism and publishing was not without its gains. In the place of hundreds of shuttered newspapers, magazines and other publications were the rise of new types of content providers. Curators, celebrity bloggers, aggregators and new tools such as Twitter and Tumblr were created, and it's difficult to make the argument that as a society, we aren't better off with today's content options than we were two decades ago, even if journalism is no longer as lucrative an industry as it once was.

Higher Ed’s Musical Chairs (With Less Chairs)

Another consequence of the changes in publishing brought by the Internet was a rebalancing of where we get our content. In the pre-Internet days, large publishers like the NY Times, Wall Street Journal and others enjoyed substantial advantages--printing press, delivery and subscriber base, advertiser and press relationships--that allowed them to cement their audience and reach, creating an oligopoly of sorts. Sure, a new newspaper or magazine could get started and make meaningful headway, but it would take a long time or a lot of money (or both) to close the gap with an established player.

As these advantages have evaporated, we have seen new and innovative content creators grow to rival or even exceed the reach of the incumbents. New publishers like the HuffingtonPost, CNET, BuzzFeed, the DailyBeast, iVillage and TMZ, as well as individual mega-bloggers like Perez Hilton, Matt Drudge and Michael Arrington now rival the largest magazines or newspapers in audience and influence.

A key lesson gained by the demise of hundreds of publishers was that when access to content is free, few are willing to pay (money or attention) for duplicate or unoriginal content. Publishers had to either innovate, or simply be the best. And much like there is little need for 40 national newspapers writing near-identical stories, there is also little need for 200 professors all delivering the same Biology 101 lectures.

Although it’s early, we can already see where MOOCs are beginning to act as gatekeepers to determine which professors offer the combination of entertaining and engaging lectures and have the solid credentials and experience to be the authority. According to David Stavens, a co-founder of Udacity, "We reject about 98% of faculty who want to teach with us. Just because a person is the world’s most famous economist doesn’t mean they are the best person to teach the subject.” Stavens sees a day when MOOCs will disrupt how faculty are attracted, trained and paid, with the most popular “compensated like a TV actor or a movie actor.” He adds that “students will want to learn from whoever is the best teacher.”

This process will only get more competitive as MOOCs begin to supplant lectures at more brick and mortar universities across the country. No less than Thomas Friedman has called on professors to raise their game, saying, "the world of MOOCs is creating a competition that will force every professor to improve his or her pedagogy or face an online competitor."

The (Growing) Long Tail

So in this new world of education, where just a handful--perhaps hundreds--of professors are teaching the vast amount of content to those in higher education in a lecture-style format, what does that mean for the rest?

If we take publishing as the example, we can expect three things to happen:

First, there will emerge a new set of tools that will give rise to new forms of educational content. Although the typical course structure has endured for hundreds of years, the format is still dependent on a largely top-down educational model that is not fit for a more fragmented ecosystem. Adobe InDesign was fine for magazine creators, but it wasn't until Wordpress, Tumblr and Twitter that publishing was truly democratized.

Second, these new tools will enable the rise of the "Alternative Professors" who will come from industry and entertainment and will aim to offer something different--a new way to learn, new skills or a new way to think. We can imagine C-level executives, famous athletes or movie stars, or innovative engineers teaching one-off courses that are attended by millions, as a way to bolster their individual brands, but also to spread educational content that has more depth and meaning than a typical blog post.

And finally, there will be a significant fattening of the "long tail." We will see the rise of millions of amateur teachers, emboldened by these new tools and seeking to help fill the gap between the small set of celebrity professors and the rest of the worlds' learners. These millions of teachers will create new and original educational content on a regular basis, shifting their focus to wherever demand is, and supplementing the content generated by the increasingly small group of celebrity professors. A few of the best of these teachers will also rise up based on their uniqueness to join the elite.

A Good Thing?

Like all changes, this creative destruction has both positive and negative implications. This approach will lead to a more agile and dynamic education system that will be able to adjust better to market forces, train our youth for in-demand jobs and careers, and retrain those that are being made obsolete by the relentless push of technology and globalization. New tools will pop up to help individuals organize and make sense of educational goals, as well as new credentials to capture this fragmented learning. It's also likely that this new world will require less physical (aka costly) infrastructure, and as a result, will offer more equal access to education, both within developed societies, and in a global context--reducing the need for sprawling (and expensive) campuses.

It is not all positive though. Research, broadly, is likely to suffer, as it will be harder to support professors in fields that are not supported by industry, such as the humanities. The quality of labs and research infrastructure will decrease with less available funding, potentially slowing progress on more difficult societal problems. The best universities will continue to prosper, but will also be forced to narrow their scope to only what they do best, as innovation in the long tail will pull the best talent in emerging fields away from them.

And finally, thousands of students will likely forego a traditional brick-and-mortar college for an online education, likely saving money, but also losing out on the invaluable holistic experience that past generations have taken for granted.

We're in the First Inning

Many of these trends are already occurring, and have been for some time. MOOCs are simply an evolution of what began with the Internet and continued with Wikipedia and Open Courseware. It is doubtful that MOOCs represent the last major innovation in how we, as a society, educate ourselves. It is more likely that this is the equivalent of Geocities, and we're still quite far away from the Wordpress and Twitters of the future. However, if history is any guide, the future of education will be cheaper, more fragmented and far more dynamic than what we've had for the last century. And on balance, that sounds like a very good thing.