In October 2013, Udemy, the online marketplace where independent instructors create and sell courses to students, announced changes in its commission structure.

At first, the changes seemed fair enough. Most of the sale price of a course would go to instructors when they recruited students through their own marketing--100%, up from 85% (minus a 3% processing fee). And on the students the company recruited, Udemy would keep 50%, up from 30%.

Soon, though, exceptions, complications and misunderstandings began to emerge. That in turn inspired a lot of conversation among veteran instructors in the virtual teachers’ lounges moderated by Udemy on Facebook groups. Some instructors left Udemy and walked into the arms of its competitors.

Six months later, I asked a variety of teachers--and some of the companies benefiting from the fallout--what they thought about the changes to the commission structure. I heard responses ranging from outrage to bemusement to sympathy with Udemy. Most of these teachers and competitors said the platform has a value that teachers should keep in mind.

But almost nobody I talked to, except Udemy, argued that the changes have worked in the favor of instructors. In fact, some say online teaching tools are changing in ways that make online course marketplaces less necessary every day, no matter what the terms.

The Initial Romance

Udemy makes it easy for solo instructors to create a course, set a price and start selling it very quickly to over 3 million potential students on the platform. Students find the courses via Udemy’s promotional channels, as well as the instructors' own efforts.

Most teachers have only one or two sparsely attended classes. Some use multiple classes to build modest businesses. And a few hit the jackpot, earning up to six figures.

What’s not so clear is which of these groups is impacted most by the changes to the commission structure. Mark Lassoff, founder of LearnToProgram Media, and one who defends Udemy’s changes, says, “a lot of the pushback has been from people who went from making $1,200 a month to $600 a month and found that enormously unfair. I see the complaining, but I don’t think people understand the bigger picture. Udemy has done the lion’s share of the marketing to procure all these students.”

That scenario may resemble what happened with Michael Williams. He has a niche business of speech therapy courses and one-on-one coaching. He publishes a few of those classes on Udemy retailing at $400, and he was earning over $2,500 per month before last November.

“One of the reasons I joined them,” Williams says, “is because I don’t have the marketing power to touch millions of people, but they do. Most of the clients who come and view my courses are from Udemy. So now essentially they’ve cut my income in half, just by that one decision.”

Others say the negative impact isn’t only on solo operations. Dheeraj Vaidya, CEO of edu CBA, which provides investment banking courses, says it was among the top instructors in the field and saw a 40 to 60% decline. “We initially felt that this would be a temporary blip,” he says. “However, we realized that the drop in revenue was more or less a fact of life.”

How 50% can turn into 25%

Perhaps more frustrating for some instructors than the actual income changes was the way this announcement was handled. It came out with little notice before it went into effect, and the original announcement didn’t highlight fine print that some feel was crucial.

Todd Charron is a business consultant and coach who was insistent enough about clarifying the fine print that he was eventually banned from discussion boards moderated by Udemy. He was increasingly annoyed by learning about catches that made a simple-sounding deal “insanely complicated.”

To illustrate, Charron outlines a scenario where his marketing drives a customer to his course. In the past he would earn 85%. The headline suggests he would now earn 100%. But, he says, “if they’ve previously signed up with Udemy, it doesn’t matter if they got the coupon code through me, it’s still 50-50.”

And in some cases, the cut is even deeper. If potential students ever signed up on the platform through certain ads that Udemy put out, “they’re saying, ‘No, they originally signed up through a Facebook ad two years ago. Sorry, you only get 25%.’”

It also turns out that Udemy claims credit for that student for life, while a teacher only gets credit for a potential new student if they sign up for the course within 24 hours of clicking the instructor’s coupon.

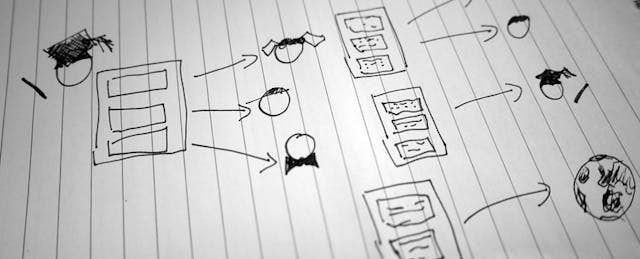

Much of the discussion after the announcement, inside the Udemy discussion groups and outside, was about trying to get these details straight. One blog post from a frustrated teacher featured an annotated payment report and a mazelike flowchart of his attempt to track when he was credited with a sale.

“There used to be a clear incentive,” Charron says. “If I want to get more, I try to market my course. But now I can do the exact same amount of marketing and not earn more. If I convince you and a friend, one of you might earn me 25%, and one of you might earn me 97%, and there’s nothing I can do to influence that outcome.”

Udemy’s Response

Udemy CEO Dennis Yang responded to my questions on these matters in writing through a spokesperson.

The new revenue share, he says, “was designed to reward instructors for being active marketers toward their own success and give Udemy the opportunity to make longer-term investments in sustainable growth. That means taking the community from the 2.5 million students we have today to 10 or 100 million students learning from tens of thousands of instructors in the future.”

To do that, they’re doubling the marketing team from 10 to 20, developing analytics that help instructors understand the audience better, expanding into mobile platforms (which now account for 30% of course consumption), growing internationally, increasing the number of organization-level customers, and making the course discovery tools for visitors more personalized.

According to Yang, “The revenue share change was not a response to changing market trends nor did it have anything to do with the health of Udemy's business (which has been and continues to be very healthy). The change was a reflection of Udemy's ambitious goal to help more students learn, to help more instructors teach and be successful, and to fundamentally democratize education.”

Yang emphasizes that fewer than a dozen instructors have “completely left” Udemy. Most of the instructors I talked to have left their old courses published, but they aren’t promoting them or adding new courses. Instead, some are taking their future business elsewhere.

A 'Walled Garden'

The tension between Udemy and instructors over revenue share will presumably be resolved by market forces, with the most valuable content going to where it can get the best price. But some instructors say the fundamental aspects of a marketplace arrangement would still be an issue even if they earned 97% of every sale.

One issue is the relationship with students. Some see Udemy as a “walled garden” where it can be difficult for teachers to carry on a connection with students outside those walls. Udemy owns the contact information on students enrolled in their classes. Sandi Lin, founder of Skilljar (an online course builder and host) says what she’s hearing from her customers is that Udemy has “become much more strict about the ability of instructors to link off to their website or promote any of their other products.”

Inherent in the marketplace model, she says, is a natural limit that most sellers can reach. “It’s a little bit like Ebay,” she explains. “It’s a way to get started and to experiment,” which leads to more buyers and sellers and the market becoming successful. “But for one particular instructor--especially people with great content --it’s becoming much harder to stand out from the noise.”

Whither the Marketplace?

Meanwhile, alternatives to Udemy are springing up that, instead of working on a marketplace model, offer white label and hosted solutions. Companies like SchoolKeep, Fedora and Skilljar aim to make it easy for individuals to build and operate courses at their own web domain. Even Wistia, which was originally only a video hosting tool, is finding that its customers are using it to hack together courses on their websites.

Think of the shift as similar to the difference between a home-based retailer selling through eBay versus one using an e-commerce software provider like Shopify to integrate search, checkout and payment tools into his own website. In the realm of online education, the latter model is becoming easier.

Some of the newest customers at these services have been big sellers on Udemy. Fedora’s founder Ankur Nagpal says his eight-month old company hosts 8 of the top 20 instructors on Udemy, “and we’re working on the other 12.”

Lin, along with SchoolKeep founder Steve Cornwell, see a trend toward teachers wanting to control pricing, marketing and student engagements. Nagpal is even more emphatic. “Education and ecommerce are converging. From the instructor’s perspective, you’re still in an ecommerce business. We want to empower to build not just great quizzes and great lectures, but also tools to build out a sales funnel for the product.”

But instead of giving up entirely on the marketplace model, these alternative solution providers advise using it in a limited way. Cornwell says, “I don’t think there’s a point where it makes sense to be completely exclusive one way or another. There is a point where you need to sit back and look at the overall distribution. The more niche of an audience you have, for example if you teach Cisco certification courses, that is where we see the diminishing value of the marketplace model and the increasing value in your own branded school.”

Likewise, Lin says she encourages people to experiment with Udemy along with their own website but to think about how to keep building relationships through channels you control.

“What is the strategy around building a following?” she says. “We have one instructor who is a self-published author and he has an online course that goes along with his book. He’s out promoting that book and giving workshops. He’s not out promoting his course specifically. He’s out promoting himself, and people are buying the course, because they like what they’re seeing otherwise.”