Buying edtech products in the K-12 market is a bit like Chatroulette: most have a vague understanding of what they want, few know what to expect, and almost no one is satisfied.

That’s the impression reinforced by a study, “Fostering Market Efficiency in K-12 Ed-tech Procurement” (PDF) conducted by John Hopkins University for Digital Promise and the Education Industry Association.

Collecting responses from a broad swath of decision-makers (including nearly 300 superintendents, curriculum directors, tech directors and principals along with 47 edtech providers), the report explores what’s working well--and the major pain points--in what can sometimes be a “dysfunctional procurement process.” It examines their frustrations for each of the following five steps:

- budgeting

- needs assessment

- finding what products to use

- evaluating product efficacy

- purchasing process

The 170-page report is dense but well-worth a read; Digital Promise summarizes the main findings in a colorful report (PDF). Here are some of our takeaways.

To Each Its Own

For vendors, few things are as frustrating as learning how to navigate the procurement process, which typically involves a decision-by-consensus approach involving several committees composed of different administration representatives. Tight budgets, strict accountability rules and the need to get input from multiple perspectives contribute to what may appear to be an unwieldy decision-making machine.

With many district and school administrators involved in the decision-making process, challenges and misunderstandings can arise due to communication breakdowns between stakeholders. Still, most of the decision-making power come from the district’s chief academic officer and technology director. Teachers and students--often the end users of the products in question--remain, ironically, only moderately involved in the process.

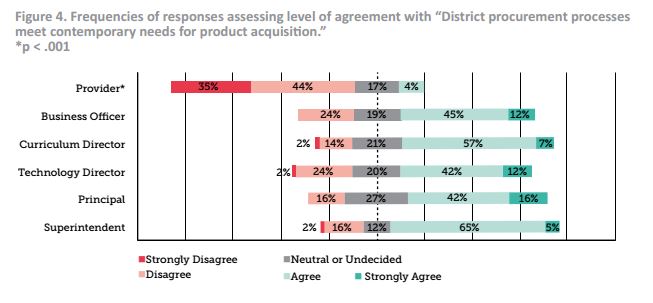

Despite the complexity, over 60% of school officials and educators reported being satisfied or highly satisfied with the decision-making process, with a similar percentage saying that the process meets today’s needs for how products should be purchased.

Unsurprisingly, the sentiment is vice-versa when one asks edtech providers, 66% of whom report being very unsatisfied or satisfied. Only 4% say the current process fits the needs of a modern procurement process. From their perspective, the experience often varies from school to school and involve different education stakeholders and rules depending on the type of product being sold (i.e., textbooks or hardware). Many vendors indicated being “mostly unsatisfied with their ability to gain acceptance or visibility within a district and with their access to district decision makers regarding the procurement process.”

Finding the Right One

Even though most district officials believe the current decision-making process is working, they have plenty to gripe about when it comes to finding the right tools that address their needs. In a nutshell, the edtech marketplace has become crowded with products using the same buzzwords and efficacy claims. One anonymous superintendent quoted in the Hopkins report said the “quantity of vendors is both a blessing and a curse.”

Big companies, with their extensive marketing resources and connections, continue to dominate, leaving startups and small companies at a disadvantage. “To the extent that discovery is restricted to a few products that districts happen to identify through searches, peer recommendations, or marketing efforts that reach them, the chances of acquiring the most effective ed-tech solutions can only be diminished.”

Compounding educators’ frustration is that even after potential tools are identified, it can be difficult to evaluate claims of effectiveness and learning outcomes. The report delivers this scathing assessment: “rigorous research evidence can be very important, where it exists and where it can be found. The reality is that the vast majority of ed-tech products don’t have any.”

Many districts refer to running pilots, ranging from 30 days to six months, along with peer recommendations when it comes to evaluating a product. But the costs of conducting pilots--including costs and staffing--and the questionable reliability of conclusions can pose a barrier.

Looking Ahead

Mired by an oversaturated marketplace and the lack of efficacy evidence, risk-averse decision-makers may lean toward working with brands they know. “Start-ups and less well-known providers have more to prove in the discovery and evaluation phase than their better-known counterparts.”

In the past years, a growing number of educators have been taking to social media--particularly via Twitter chats--to share useful tools. But these educators are part of the pioneering minority. The report recommends “creating a national website to provide information about available products and where they are being used.” (Hint hint.)

This detailed report expands on some of the ideas raised by Digital Promise and IDEO in an earlier report that also explored the procurement challenge. In addition to creating a centralized website of market and review information about edtech products, the John Hopkins researchers offer other recommendations to simplify the process for all parties involved:

- getting schools and districts to publicize their instructional needs;

- creating guidelines to evaluate product efficacy;

- involving end users--students and teachers--more in the process;

- increasing transparency in state and local purchasing policies.

These insights and lessons offer valuable guidance in bringing bringing states, districts and industries together on the same page when it comes to procurement. After all, marketplaces tend to operate best when there are no alarms and no surprises.