Editor’s note: This post was first published on Wiley’s blog and has been edited.

For almost three years Lumen Learning has been helping faculty, departments, and entire degree programs adopt open educational resources (OER) in place of expensive commercial textbooks. In 2014 we got a grant from a Gates Foundation competition to create next generation personalized courseware. We’ve spent the last year working with roughly 80 faculty from a dozen colleges across the country co-designing and co-creating three new sets of “courseware”— cohesive, coherent collections of tools and OER that can completely replace traditional textbooks and other commercial digital products.

As part of this work we’ve been pushing very hard on what “personalized” means, and working with faculty and students to find the most humane, ethical, productive, and effective way to implement “personalization.” A typical high-level approach to personalization might include:

- building up an internal model of what a student knows and can do,

- algorithmically interrogating that model, and

- providing the learner with a unique set of learning experiences based on the system’s analysis of the student model

Our thinking about personalization started here. But as we spoke to faculty and students, and pondered what we heard from them and what we have read in the literature, we began to see several problems with this approach. One in particular stood out:

There is no active role for the learner in this “personalized” experience. These systems reduce all the richness and complexity of deciding what a learner should be doing to—sometimes literally—a “Next” button. As these systems painstakingly work to learn how each student learns, the individual students lose out on the opportunity to learn this for themselves.

Continued use of a system like this seems likely to create dependency in learners, as they stop stretching their metacognitive muscles and defer all decisions to The Machine about what, when, and how long to study. This might be good for creating vendor lock-in, but is probably terrible for facilitating lifelong learning. We felt like there had to be a better way. For the last year we’ve been working closely with faculty and students to develop an approach that—if you’ll pardon the play on words—puts the person back in personalization. Or, more correctly, the people.

It’s About People

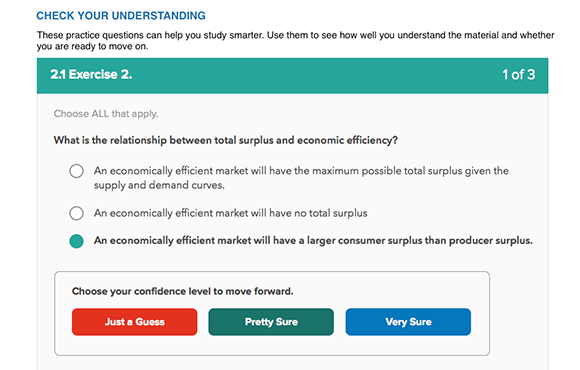

Our approach still involves building up a model of what the student knows, but rather than presenting that model to a system to make decisions on the learner’s behalf, we present a view of the model directly to students and ask them to reflect on where they are and make decisions for themselves using that information. As part of our assessment strategy, which includes a good mix of human-graded and machine-graded assessments, students are asked to rate their level of confidence in each of their answers on machine-graded formative and summative assessments.

This confidence information is aggregated and provided to the learner as an explicit, externalized view of their own model of their learning. The system’s model is updated with a combination of confidence level, right / wrong, and time-to-answer information. Allowing students to compare the system’s model of where they are to their own internal model of where they are creates a powerful opportunity for reflection and introspection.

We believe very strongly in this “machine provides recommendations, people make decisions” paradigm. Chances are you do, too. Have you ever used the “I’m Feeling Lucky” button on the Google homepage?

If you haven’t, here’s how it works. You type in your search query, push the “I’m Feeling Lucky” button, and—instead of showing you any search results—Google sends you directly to the page it thinks best fulfills your search. Super efficient, right? It cuts down on all the extra time of digging through search results, and compensates for your lack of digital literacy and skill at web searching. I mean, this is Google’s search algorithm we’re talking about, created by an army of PhDs. Of course you’ll trust it to know what you’re looking for better than you trust yourself to find it.

Except you don’t. Very few people do— fewer than 1% of Google searches use the button. And that’s terrific. We want people developing the range of digital literacies needed to search the web critically and intelligently. We suspect—and will be validating this soon—that the decisions learners make early on based on their inspection of these model data will be “suboptimal.” However, with the right support and coaching they will get better and better at monitoring and directing their own learning, until the person to whom it matters most can effectively personalize things for themselves.

Speaking of support and coaching, we also provide a view of the student model to faculty and provide them with custom tools (and even a range of editable message templates written from varying personalities) for reaching out to students in order to engage them in good old-fashioned conversations about why they’re struggling with the course. We’ve taken this approach specifically because we believe that the future of education should have much more instructor-student interaction than the typical education experience today. Students and faculty should be engaged in more relationships of care, encouragement, and inspiration in the future, and not be relegated to taking direction from a passionless algorithm.

A Milestone

This week marks a significant milestone for Lumen Learning, as the first groups of students began using the pilot versions of this courseware on Monday. Thousands more will use it for fall semester as classes start around the country. This term we’ll learn more about what’s working and not working by talking to students, talking to faculty, and digging into the data.

This stuff is so fun. There’s nothing quite like working with and learning from dozens of smart people with a wide variety of on the ground, in the trenches experience on the teaching and learning side, and being able to bring the results of educational research and the capabilities of technology into that partnership. You never end up making exactly what you planned, but you always end up making something better.