See if this problem-solving technique sounds familiar: form a hypothesis, design an experiment, measure the results, and use the findings to inform the follow-up experiment.

Science teachers might recognize that as the “Scientific Method.” Entrepreneurs have their own name for it, too: the “Lean Startup,” popularized by Eric Ries’ book of the same name, which has been canonized in the lore of entrepreneurship.

The core tenets in these two approaches are not all that different: Like any startup, a classroom must deliver services under unpredictable conditions. Like entrepreneurs, teachers continuously improvise new approaches, measure if they work, and learn from their successes (or failures) immediately. Are the students learning? What’s working? For all students, or for some?

No solution is perfect, but the Lean process can help both entrepreneurs and educators avoid costly stumbles by laying out a series of steps to test and measure in a consistent—and efficient—manner. Few emotions are as draining as finding out that a product or teaching method ultimately doesn’t work—and not knowing it until it’s too late (or at the end of the school year).

Already, the process is being used for new instructional approaches in places like Summit Public Schools. In fact, CEO Diane Tavenner gave a talk in 2012 on how she and her team used the method to test and refine Summit’s instructional practice (see video below). And the result? Since launching in 2003, Summit has graduated more than 1,700 students, 100% of whom meet or exceed 4-year college entrance requirements.

When it comes to teaching, being able to quickly understand whether or not your students are learning—and then adjusting your practice accordingly—is crucial to the profession. So how can educators co-opt Lean Startup methods—a series of rapid testing processes designed to test and scale businesses—to design the best possible classroom?

Part 1: Construct and Build Your Experiment

Define Your Problem and Decide What You Want to Measure

Before any experiment, one must ask: What do I want to know, and what are the meaningful metrics that inform whether or not the experiment is working?

When teachers writes lesson plans, they ask themselves, “What do I want my students to know, and how will I measure it?” There are always go-to, multiple-choice tests. (Big surprise.) But finding the right metrics isn’t always that obvious—especially because no one agrees on how student learning should be measured.

Perhaps you’d like to see how well students grasp content, which you can measure with exit tickets at the end of the lesson. Maybe you’d like to know how many students are engaged by tracking how many times your students ask questions or complete various components of a lesson. Or, maybe you’d like to gauge if students enjoy the lesson by surveying them to see what they did or did not like about a lesson or activity.

A word to the wise: be careful that you’re measuring actionable metrics, as opposed to vanity metrics. The latter are numbers that look good on paper and, in some cases, can be gamed, but don’t really mean anything important about a student’s learning process. For example, a math teacher may be delighted to see students aceing a multiple choice test. But that isn’t necessarily helpful, as he or she doesn’t know how the student arrived at that answer. Actionable metrics, on the other hand, give the teacher information that they can use to directly affect their practice—that tells them where learning might have gotten interrupted.

- Mary Jo’s Example: I’ve decided that in my hypothetical middle school science classroom, I want to measure how many of my students can successfully diagram a food chain, including herbivores and carnivores.

Create a Hypothesis and Develop Your ‘Lean’ Product

Now that you know what you want to use to measure, you can start designing your experiment. What’s your hypothesis, and what kind of instructional approach or product do you want to test?

Any solid hypothesis begin with an exploration into what the “end user”—in this case, students—wants and will respond to. Empathy is a key component to any design-centered approach to problem solving, so reach out to students and understand their needs. If you’re able to answer these questions below, you lessen the risk of being overly-influenced by your own biases, or that of your school, district, or state.

- Do students recognize that they have a need or dearth that you are trying to fill or address?

- If there is a way to address that need, will students buy into it?

- Knowing what you know, can you fill that need?

These answers should help you decide on a hypothesis—which is eerily similar to a lesson objective, or a SWBAT (Students Will Be Able To) statement. Except, in this case, you’re adding an action (A) before the objective (B), in the form of “If I do A, then the student will be able to B.”

And once you’ve got your hypothesis, it’s time to bring in the MVP. Entrepreneurs abiding by the Lean Startup methodology often talk about a “ minimum viable product”—defined as the most basic version of a product. Your MVP is what you test, so it could be an instructional strategy or a tool. But the MVP doesn’t have to be perfect by any stretch of the imagination prior to testing, and chances are, it won’t be. You want it to be basic, yet effective. I’ll include a non-technical example below

- Mary Jo’s Example: My hypothesis will be that if I deliver my “introduction to new material” through a hands-on activity rather than through a lecture, students will be able to more successfully diagram a food chain. My MVP is the hands-on activity.

Part 2: Test, Test, Test and Measure

Track Progress Through Feedback Loops

Now that you’ve got your experiment designed, let’s see how the students do!

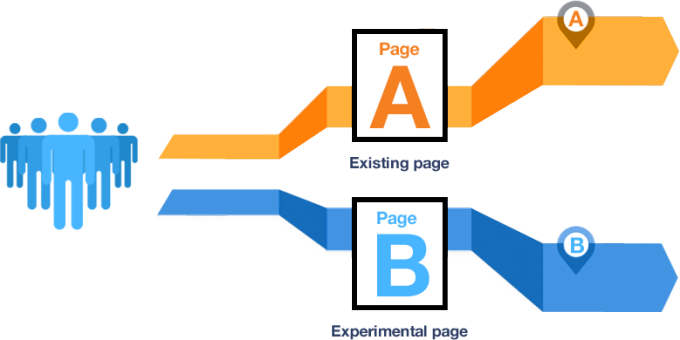

Quickly testing and finding out the results of your experiment is easier if you can test one group of students with the variable and one without. This is what entrepreneurs call A-B testing. This type of testing (shown below) is perfect for a teacher with multiple classes. You can run each version with different classes, and then compare the outcomes.

How long should each test take? Tavenner and her Summit Public Schools team ran experiments that only lasted a week, using their learnings to shape their school model. Tavenner reports in her video keynote above that her and her team learned more in 14 weeks than they did in the previous 8 years of the charter’s existence.

- Mary Jo’s Example: Time to test. My periods 1 and 2 received the hands-on activity, while periods 3 and 4 got the lecture. Looks like periods 3 and 4 performed better in diagramming a food chain. Periods 1 and 2 still seemed to miss the fact that the food chain is a cycle. I think it’s time to try this again, but instead of the hands-on approach, let’s try using a Khan Academy video to deliver the instruction.

Part 3: Learn and Adapt

Accept that Your Role Might Change

Once you have run your experiment and data about whether or not your students learned, it’s time to redesign the experiment and test again. And again. And again.

As you continue to learn, you may find that your role in the classroom changes. You may find yourself falling towards one side of the “sage on a stage” vs. “guide on the side” debate, for example. You may find that a hands-on science activity that puts students in the driver’s seat delivers the best results. Or, your class may still respond best to an awesome lecture that you’ve diligently prepared.

But as with all lean things, being adaptable is key. As Stanford professor Robert Sutton says:

“The best people and organizations have the attitude of wisdom: The courage to act on what they know right now and the humility to change course when they find better evidence.”

Constantly Ask, ‘What Defines “Success” in the Classroom?’

As your continue to iterate (or change up your experiments), you might find that other stakeholders around you—parents, other teachers, administrators—influence what metrics define student success. Whether they lightly or forcibly influence them… well, that’s unpredictable. But if you, your parents, your students, and your administrators can agree on those common goals, then well.. shoot for them.

Becoming lean is a learning experience, and it isn’t for the faint of heart. But if you carry it out effectively, long gone will be those late days in May when teachers say to themselves, “I wonder why my students understand X and not Y.” And for the record, you might already leaner than you think—you just didn’t know it until right now.

And by the way, there’s one final step… SHARE. Are you using lean in your classroom? Drop us a note, and we may want to profile your classroom on EdSurge.