Lately I’ve seen quite a few edtech companies that hope to graduate from offering a free product to actually monetizing it. Perhaps that’s a sign of their business’ growing maturity, or maybe it’s because in today’s tighter investment climate, their investors are urgently demanding to know how they will make money. Either way, it is important for all edtech entrepreneurs, especially those who develop instructional technology for use by teachers and students in the K-12 grades, to understand how to position their products for maximum sales success.

Based on my experience in the enterprise software world and now in education technology, I’d like to offer some of my thoughts on how to go about doing this.

How do your customers see you?

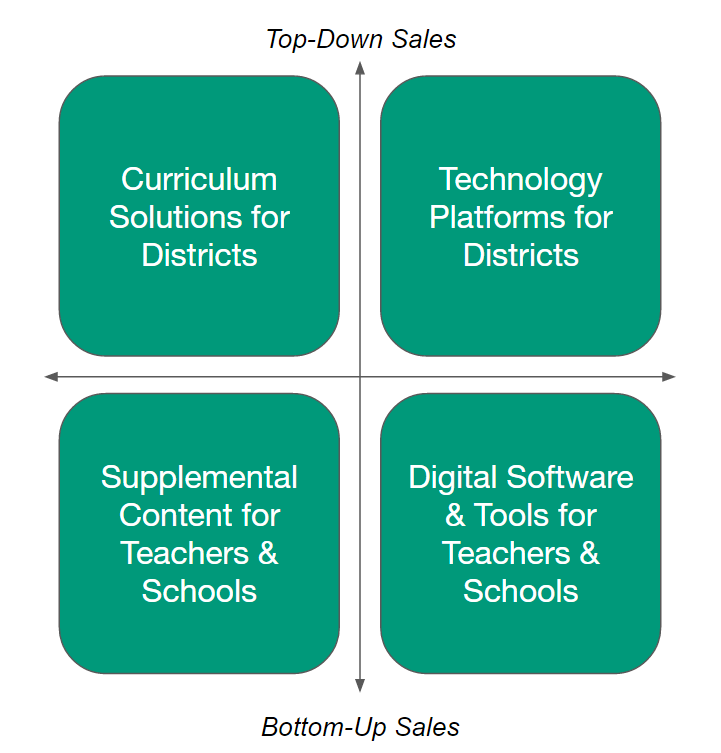

It is helpful to first try to accurately categorize your product in a way that is consistent with how your buyers view it. If you’ve built an instructional technology product, does it solve an entire curriculum need in a school or district, or is it a supplemental educational resource? Is it mainly a digital software tool for a specific instructional or administrative task, or a broad-based technology platform that an entire school or district must adopt?

I realize that many venture capitalists prefer to see business plans bejeweled with words such as “curriculum” and “platform” since these are generally perceived as having greater value than more narrowly focused descriptions such as “content” or “tools.” But I ask you to be honest with yourself in this matter. An accurate answer will help you best position your product for eventual sales success.

Here are four statements you can make about your product. See which category you belong to—and choose only the one that best fits you.

1. My product offering consists of a comprehensive solution of educational content, tools and professional development that can fulfill the standardized curriculum needs for a particular subject and/or grade level for an entire school district/state/region.

2. My product offering consists of proprietary content and tools designed to teach a particular topic or skill, but is not comprehensive enough in scope to be unambiguously included in Category 1 above.

3. My product offering consists mainly of digital software and tools that solve a specific instructional, administrative or infrastructure need for teachers and/or schools.

4. My product offering consists mainly of digital software and tools that solve a broad-based instructional, administrative or infrastructure need in schools and/or districts and is designed to operate seamlessly as a platform for third party tools and content.

If you picked statement #1, you are in the Curriculum Solutions category. If you picked #2, you are in the Supplemental Content and Resources category. If you settled on #3, then you are in the Digital Tools category, and if your work is best described by #4, then you are in the Technology Platform category. Figure 1 summarizes this in a simple quadrant.

Why your position in the Edtech Products Quadrant matters

Knowing where you fit is crucial because it defines the scope of your market. It helps you recognize where the dollars are in a typical K-12 school district that could be spent on your product. It can also help you narrow down how you should price your product and who is likely to make a decision about buying your product. These factors, in turn, will dictate both the financial model for your company and the type of sales and marketing organization you’ll need to efficiently win customers.

Just about every educational technology product I’ve seen best fits in one section of this quadrant.

You can build a successful business regardless of which section of the quadrant you are in! But it’s important to get your positioning right the first time to avoid a painful reset in later years.

Supplemental Educational Content and Digital Tools are best sold “bottoms up”

Say your product is mainly focused on delivering subject-specific content that will be used by individual teachers at their discretion, or even digital tools for a narrow instructional or administrative task. For these offerings, you’ll need a supplemental tool marketing model. In this case, I would generally advise you to take a “bottoms-up” sales approach. Be prepared to offer a generous trial-use policy or a limited-use free product for teachers so they can recommend it to their peers and build up greater demand from within their school before you approach their principal with the prospect of a premium product purchase.

The typical district budget for supplemental educational products is smaller than that designated for core curriculum educational material. On the other hand, the authority to spend money on such products can often be widely dispersed or rest in the hands of school principals, especially for single-school sales below $5000 a year.

This kind of sale is frequently managed by a centralized telesales staff and (in some cases) could even take place via a self-service, credit-card-based website, especially if the product feature set is simple and the pricing is low enough that schools will not feel compelled to negotiate for discounts.

The administrator of a small district who wants to buy the same product for the entire district can be handled quite easily via a centralized telesales model (possibly with some price negotiating involved). If a bigger sales opportunity emerges (for instance, exceeding $50K), your company can always fly in a senior executive to close the deal. But in general the low price point of each sale dictates that it should be done with minimal sales touch.

Alternatively, if your customers are students or parents directly (e.g. early reading software for very young children, supplemental online math tutoring at home, etc.) then your product lends itself best to a consumer marketing model. Be warned: this is an expensive route to take and your product will need to achieve massive volume to succeed.

To drive massive scale, your product will likely be priced less than $100 per year and the software will be web-based or delivered as an app. Your products need to be truly simple to use by children (and in some cases their parents!) to generate enough viral buzz. Word-of-mouth advertising is crucial.

Often these products feature a free trial period for consumers, or a classroom-use freemium product for teachers, so that they can recommend the full version of the product to parents.

Supplemental educational content companies that are in the direct-to-schools category include Newsela (ELA), NoRedInk (ELA/Grammar) and Front Row Education (Math/ELA). An interesting example of a digital tool company for supplemental learning in K-12 schools is EdPuzzle (which teachers can use to create customized lessons using free video resources on the Internet). A great example of a widely used for-profit company that offers early education software for very young children direct to parents is ABCMouse. And examples of district-wide technology platforms include Learning Management Systems (LMS) like Blackboard and Scholastic. (Full Disclosure: I am an investor in Newsela, Front Row Education and EdPuzzle.)

Curriculum Solutions, Tech Platforms: Taking it from the top

In the US, and in most western nations, K-12 education is a public good. As such it is highly standardized and regulated. Public schools will remain—despite the protestations of many who decry their deficiencies and would like to do away with them altogether in favor of charter or private schools of choice.

As a for-profit entrepreneur, you can’t afford to target just private and charter schools because there simply aren’t enough to generate adequate revenue to build a viable company (though many of them can be very enthusiastic early adopters).

States and education districts have bureaucracies responsible for delivering primary and secondary education to all kids in their region and have long put a high value on standardization and central control. In a world of paper-based textbooks, this usually meant that a single vendor would get a contract for textbooks in one or more subjects, and the textbooks would be accompanied by standardized lesson plans that each teacher is supposed to follow as the school year goes by. To avoid charges of favoritism, such contracts typically go through a competitive bidding process.

In the evolving world of digital education, textbooks are being replaced with infinitely customizable and searchable digital content, packed with interactive resources such as videos, animations and games. But old habits die hard: public education systems still lean heavily on standardized curriculum and competitive bidding. Hence an education technology startup that aims to sell digital curriculum to a school district needs to recognize that in order to be even considered for a deal, it must bring credibility as a vendor among district officials. (“Nobody ever got fired for buying IBM.”)

In an all-digital world, and especially with newer skills-based standards such as Common Core, there is greater leeway for teachers to deviate from what is prescribed in textbooks and lesson plans. Schools can also supplement the curriculum with online digital resources. But standardized curriculum hasn’t gone away. Those choices are typically made by administrators and education experts on a district curriculum committee. Standards compliance and monitoring become paramount and you need to help districts achieve these goals. At the same time, your product must get good reviews from teachers and school principals down the line, otherwise you may succeed in selling—but not getting your product implemented or renewed.

Therefore, if your company has developed an educational curriculum solution that is best implemented across an entire school district, or your product is a district-wide technology platform that automates certain tasks across the district (such as a learning management system), you must be prepared to sell top-down to the districts. This will also require supporting extensive pilots that bring together educators and administrators in making a final choice. In order to be successful at this game, you need a district sales force that can handle long sales cycles and expensive, competitive bidding processes against well-financed vendors.

District sales organizations are more expensive so your product needs to be, too. My general rule of thumb is that you should not be undertaking district sales via a field sales organization if your minimum sales order from a district is less than $50K and your average order across all districts is less than $100K. Here is how the calculation works.

A high-performing edtech field salesperson typically can make $150K to 200K salary, plus commission, in a year. You can often spend an equal amount or more in overhead sales costs (such as sales support people, sales management, and travel expenses). Add them up, and you may be looking at spending $300K to 400K annually simply to field a single regional sales office. If—and this is a big if—this salesperson can achieve revenue (or bookings) of $1 million in a year, then you’re spending 30 to 40 percent of your revenues in direct sales expenses, leaving you a healthy margin to pay for building and supporting your technology.

But if the salesperson only wins $500K in revenues in a given year, you are barely covering your selling costs and there is nothing left over to pay for other operating costs including R&D, IT operations, marketing, customer support, and general administration. So you need to be targeting a minimum of $1 million in revenues per year per salesperson.

If a minimum sales order per district customer is for $50K, a salesperson will need to win 20 new sales orders of that magnitude to make their annual target revenue. Even if some individual district sales orders are larger and the average is $100K per sales order, the salesperson would need to win an average of 10 new sales orders in their first year—or almost one new order each month.

In an early adopter market environment, each sale can take as long as 12 months, so it may be difficult to achieve that many orders within the first year. This threshold may be especially difficult to achieve if the product and decision-making is complex, extending the sales cycle. So if you cannot average around $100K per order, or justify a purchase of at least $50K per order for your product, it is extraordinarily difficult to build a profitable field sales organization, at least not one for a high-growth startup without an entire portfolio of legacy products.

To field an effective district sales force, you’ll need to make a significant investment upfront in experienced field salespeople to cover all the major regional territories in the US, without much hope that the team will pay for itself in its first year. Usually a startup has to go through a few product iterations before getting its product right. In the meantime, management will have to contend with salespeople who quit or are not right for the job.

Here’s my bottom line: If you have an educational technology product that requires a top-down district sales organization, make sure to raise a lot of investment capital and be prepared to spend at least a couple of years refining your product and your sales organization before you can count on making profits.

Does offering a SaaS product vs. a software license sale make a difference?

The above analysis was done without considering whether the product was sold as a Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) subscription, or a one-time software license sale. Deciding between a bottom-up or top-down sales approach still depends mainly on the complexity and price of the initial sale and the type of buyer, which in turn is dictated by whether the product is supplemental content or a full curriculum solution.

Renewal sales are key to making a SaaS model work, especially after the first couple of years of operation.

Since the entire idea behind a SaaS business is to offer a tool for a recurring subscription fee, it stands to reason that after the product has been baked into a district’s processes and budgets, the subscription renewal effort should not require as much effort as finding new customers (as long as you’re keeping your customers happy!).

That means it makes sense to separate the annual renewal activity from the customer acquisition activity by having two different types of salespeople: a “farmer” type that can work from headquarters within a lower-cost telesales group, and a “hunter” type that is regionally based (and more expensive). This type of sales specialization can lead to greater sales efficiencies and help achieve faster growth and profitability. But it does require you to build a more complex sales organization and compensation structure. Luckily, this is not rocket science since these types of organizations have been perfected many times over by Enterprise SaaS sales organizations.

Evolving? Bottoms-up to top down?

Half steps are always hard: Plenty of companies may be part way to implementing a product vision. For instance, a company may have enough supplemental content or an intriguing tool—but it’s not quite comprehensive enough to be a full curriculum solution. Then what? Can you start with a bottoms-up sales strategy, and evolve to the more expensive, top-down strategy later?

Answer: it’s complicated!

There are organizational and cultural impacts of how you position a product or build a sales model. In a future article I hope to share how those choices shape your company, how they impact your company’s long-term financial and profitability, and, yes, the potential risks involved in moving from one model to the other.

For now, I hope I’ve convinced you that accurately positioning your education tech offering is critical to your success. It will dictate who will buy your product, what you can charge for it and how you can best sell it.