James Paul Gee is living many a teenager’s dream. (Or mine, at least.) The Mary Lou Fulton Presidential Professor of Literacy Studies at Arizona State University has been playing video games for four hours every day since 2003, solving puzzles and battling bosses in games such as Doom, Darksiders 2 and Uncharted 4.

Gee lives on a small farm, and when he’s not busy feeding donkeys or mashing buttons, he’s writing about what he’s learning about learning from video games. Gee has authored and edited many books examining the intersection between gaming and learning (in addition to his prolific writing on literacy and theoretical linguistics). He’s also a frequent speaker at gaming events including Game Developer’s Conference and Games For Change.

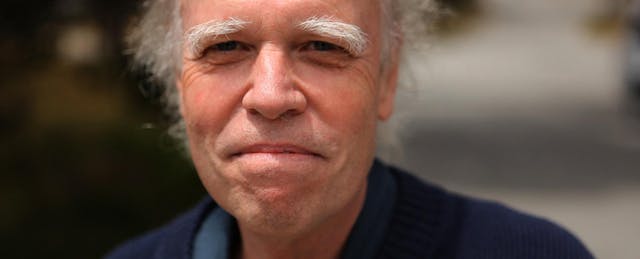

His next speaking gig will be a keynote at the Intentional Play Summit in Mountain View, CA on Oct. 7, 2016. We caught up with Gee to learn about what games he’s currently playing, what he’s learning, why he doesn’t trust people who don’t finish games, and how it feels to be one of the most respected voices in the game-based learning community at the ripe age of 68.

EdSurge: What was the first video game you played?

Gee: The first game I played was Adventures of the New Time Machine, in 2003. You had to fight and solve puzzles. The game was long and hard. It was utterly frustrating.

But as an old person, I realize we don’t often get to learn new things. We rest on our experience and we’re really well-practiced, so we look smart. But when we have to learn something new, we have to confront ourselves as a newbie, as a brand new learner for the first time in a long time. And it’s not a pretty sight. So I realized gaming is really both frustrating but life-enhancing. I’m confronting how bad I am at learning after all these years, and getting a whole new opportunity to do it in a game setting.

As I played more, I realized I’ve got to start writing about this, because that way I can keep my career. One of the great things about being an academic is you can write about what you want.

What did you play afterwards?

The second game I played was the first Deus Ex, which is a revered game. By this time, I realized there’s a whole community of gamers out there. Gaming is not an isolated activity, and games have values and judgment systems that can help you get along. It taught me that the type of intelligence, learning and development gamers engage with is very social.

How do you relate your early gaming experiences to education?

Baby boomers like me inherited from the school system a view of intelligence that says whoever is quickest and most efficient to the goal is smartest. If you learn algebra in six weeks and I learn it in six months, you’re smarter than me. If your proof is 14 lines and mine is 20, you’re smarter than me. That’s a really bad view of intelligence.

Gaming culture incorporate a different view of intelligence that says, “Try lots of things, take risks, fail. If things don’t work, rethink them. Let’s think laterally, not just linearly. Don’t try to rush to your goals in the fastest and most efficient way, because you may miss a bunch of stuff.”

What was the last game you beat?

I’m just about one boss away from finishing Darksiders 2. The last game I beat was Uncharted 4; the new Doom before that. The next game I’ll play is the newest Deus Ex.

I tend to finish the games I play. In addition to not trusting people who don’t play games, I also don’t trust people who never finish them. A lot of good game designers never finish a game, because they think they know so much that they can predict how it is going to end. But that would be like saying, “I know a lot about novels, but I’ve only read the first chapter.”

Have you recently played any game explicitly marketed as an educational game?

I don’t tend to play educational games. The only time I play them is because loads of people send them to me, and the vast majority of them are terrible. Not all of them, however. I really admire Dragonbox. It’s a spectacular game, absolutely entertaining, and absolutely true to algebra in a very deep sense.

One of the reasons so many educational games aren’t very good is because it’s hard to make a good game. The heart of a good game is marrying the content—which is problems to be solved—with the game mechanic. And this marriage usually also requires great art.

But aren’t you also actively involved in helping educational game developers?

I helped start Filament Games, which develops some of the most widely-used educational games, with people who were my students. I’m also on the board of iCivics, which has made many games for former Justice Sandra Day O’Connor to teach civics digitally. The games are used in all 50 states and has millions of players. Fifty percent of all the social studies teachers in the country use it.

I’m not anti-educational games. I just like good ones.

Have your thoughts about the role of video games in schools and classrooms evolved over time?

They’ve evolved less than what people would realize, because I was never claiming we should bring games to school. I’ve always claimed that we should bring the deep ways of teaching and learning that game designers use in order to motivate problem solving to school, whether or not teachers and students use a game.

Game designers are not just designing a piece of software. They’re designing an interest-driven community. They’re creating affinity spaces where people come together to take the game further—mod it, review it, strategize and share. That sort of social interaction among a passion-driven group of people keeps the game alive and creates a tremendous amount of new knowledge.

I would like to see the same in school. I’d like to see curriculum that offers a set of problems with a very good mechanic to solve them, and also connected to social activities and participation spaces in and out of school, so kids can be proactive and take it further, learn collaboratively, and even learn to design.

What are the challenges facing educational game developers today?

If you haven’t got a business model to make it sustainable and credible, it doesn’t matter how good your game is. When the MacArthur Foundation, and then later the Gates Foundation, funded these projects, what none of us realized is the importance of having a sustainable business model. We were coming into this to learn about an interesting problem, do research and make good games. No one really cared about the business.

Creating a sustainable digital media is very difficult. Like everything in America, business is often deeply controlled by monopolies. There are publishers like Pearson, tech companies like Microsoft, Facebook and Google. And for a startup to get past those monopolies is very difficult.

Educational game developers usually try to sell into schools. That’s when they run up against big publishers, along with the connections and other political advantages that those large companies have in schools. Now, it’s not that these hurdles can’t be overcome—iCivics did it—but it’s a really tough problem.

You have become one of the most well-respected thought leaders in the game-based learning community. How has this community evolved over time?

The community has gotten massive. You know, what the heck? Before, there was an older movement around simulations, but it was pretty small. Now it’s become a huge community, partly because there’s a new generation of academics, and the 30-year-olds now coming into the workforce are gamers.

One thing I predicted that happened is that the world of games for impact has split into two camps. In one, you have a group of people who believe that gaming can really introduce a whole new paradigm of how people teach and learn. Learning isn’t restricted to one classroom; rather it’s based on problem solving regardless of space or medium. Gaming actually celebrates failure rather than punishing it. This paradigm could lead to deeper learning, creativity, more equity and more chances for poor kids to get 21st century skills.

The other camp says: “Wow, this is powerful technology, by which we can do better what we’re already doing in our schools.” In other words, we can make games shinier and better, but we’re going to continue the paradigm we have.

Are there voices left out that should be a part of the game-based learning community?

[In the early 2000’s] there were certain voices left out, such as assessment people like psychometricians. The community was not that interested in learning and cognitive scientists, yet those are the people whose research would give it due diligence and validity. But you can’t develop games and say, “‘I’m going to change learning, but I’m not going to bother to assess it to tell you it works.” So I worked heavily with MacArthur [Foundation] on assessments.

Right now, it’s not so much that I think that there are voices left out, it’s that we are going into silos. It’s always a danger when things get big; research suggests that the largest sort of community of interaction that humans can cope with is no bigger than 200 people in a face-to-face way. When that happens, you lose the diversity.

It’s also not clear what all these silos are. For instance, you’ve got augmented reality, the virtual reality. You’ve got people saying, “Look, it’s really about experience design. It’s not really about games, but rather how we could design educational experiences in the real world.”

How has the world of gaming changed?

I think what we’re going to see here is tremendous proliferation of different genres. Keep in mind, the best-selling game in history was Sims. From the day it came out, people have said it isn’t a game. Right? And it’s the best-selling game.

Now there is what I consider a new genre of games, such as Gone Home or Gone to Rapture, where you’re essentially walking around the world to uncover a story. What it really is, is a kind of new form of literature. These games are not “choose-your-own adventure,” they’re about putting the pieces together, and if people put them together in a different order that will change the story.

It’s important to get a diversity of perspectives in these conversations, especially from newer people who might know stuff that us old guys don’t know.

Any teaser about what your will talk about during your keynote at the Intentional Play Summit?

I was in my fifties when I started playing and writing about games. I’ve only been doing it since 2003. In that time, I’ve went from being the new boy on the block to the gaming guru to many people probably wondering whether I’m even still alive.

As an academic field, the history of educational gaming should be at least 100 years. Now there are so many, many more people in it now, that I’m viewed as like a great, great-grandfather.

The talk will be partly a retrospective about my joys and sorrows and regrets, and about where I think we are, what the dangers are, and where I personally hope we can go. But it won’t be me going there. I told Henry Jenkins [Professor of Communication, Journalism, and Cinematic Arts at the University of Southern California], one of the first people I met who was into games: “You know, we can study games and we can sort of point to the Promised Land, but given our age and our positions, we’re not going to the Promised Land.”