With headlines like “Virtual Reality Learns How to Get Into Classroom,” which The Wall Street Journal ran this February, the hype cycle around VR’s potential in education has returned.

This time, a medley of new players—especially technology magnates—are jumping in the fray: Facebook has committed to pour money into developing education apps for its $600 Oculus Rift. On the other end of the market, Google is offering its $15 Cardboard alongside Expeditions, which takes viewers on virtual field trips. The search giant is also working with Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, a major education publisher, to create content and lesson plans for classrooms. Meanwhile, startups like Nearpod are introducing virtual reality lessons to prime the market.

Even one charter school, the Washington Leadership Academy in Washington, D.C., is venturing into the reality space. It nabbed one of the $10 million prizes from the XQ: Super School Project in part for its plans to develop the first-ever virtual chemistry lab, among other ideas it has for the technology.

But as the hype and hope build, some temperance is appropriate. This isn’t the first time educators have speculated that virtual reality would sweep through America’s classrooms.

Aaron Walsh, director of the Immersive Education Initiative, founded the immersive education field in the 1990s. Through that decade, a smattering of educators began experimenting with virtual reality. Bryan Carter, a professor at the University of Arizona, built Virtual Harlem, for example, as a way for students to explore and experience the Harlem Renaissance during the 1920s Jazz Age.

With the explosive growth of online learning in the late 1990s and early 2000s, there was widespread speculation that new online courses would soon incorporate immersive environments. But it didn’t happen. Internet bandwidth constraints, limited devices, poor graphics, and struggles to fit virtual reality into the traditional class period consistently held back virtual reality’s march into schools.

Then there was Second Life. At its peak in 2010, 1.1 million people created accounts, adopted avatars, and played out their lives in this online virtual world. Some educators built lessons around the program and invited students to learn in the immersive environment, while others held virtual conferences there.

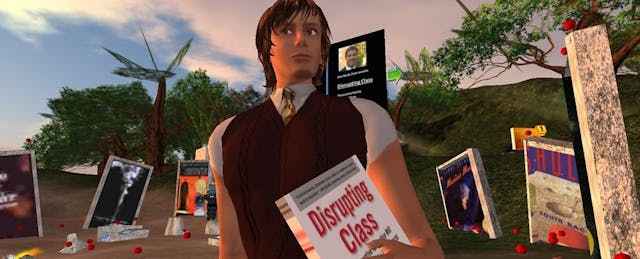

Shortly after Disrupting Class was published in 2008, I spoke at several virtual conferences held in Second Life. As I would settle in front of my computer in my small apartment in San Mateo, Calif., dozens of educators filled the virtual spaces that others had created to host the events. Some listened attentively and asked great questions that sparked great conversations. Others taught me how to use my avatar (and one educator actually created my avatar for me—Innosight Skytower was no joke). But I also remember some educators flying aimlessly around Second Life as I spoke, teleporting in and out, and taking off their virtual clothes in what was either a time for experimentation or a not-so-subtle protest. I could never tell, even as it gave new meaning to the advice to speakers to “picture the audience in their underwear.”

But as Second Life’s users declined over time, it faded from the popular imagination and educators’ lesson plans. What seemed like a transformation turned out to be a fad.

There are also serious questions about the potential effects of virtual-reality experiences on growing bodies and brains, especially in young children. As Wayee Chu, a partner at Reach Capital, told me in an article for Education Next, “No one really knows the impact or effects [of these experiences] on the developing brain.” She advises that hardware headset manufacturers exercise caution as they market to children. “Like any new technology, you don’t want your kid or adult in front of the screen for extended periods.”

Stanford University’s Virtual Human Interaction Lab has been researching this area for more than a decade, but it’s still early in the process. As Jeremy Bailenson, the director of the lab, told CBS News in June 2015, “In general we don’t know what happens when a kid puts on a helmet.” An earlier study from 2009 raises questions about children’s abilities to fully understand what they have encountered; it found that about half of children who had experiences in virtual reality recalled them as if they had occurred in the physical world—a powerful but also troublesome finding.

But while virtual reality devices from just five years ago were available mostly for researchers or hobbyists, today’s consumer headsets will become more affordable and widely available in the years to come, with better performance and expanded apps for their use. Still, their eventual impact on education remains unclear.

Although there are plenty of reasons to believe that this time is different—bandwidth is better in schools, devices are falling in cost, players are investing in content creation and lesson plans that have a higher likelihood of working in schools—there remain few initiatives to train or support teachers to incorporate virtual reality into student lessons in meaningful ways. It is uncertain that implementation could be done at scale.

The potential of virtual reality to engage students is as intriguing as ever, but it’s also not the first time we’ve heard the hype.