By far, one of the most popular topics at the iNACOL conference in San Antonio last week was “competency-based learning"; out of the conference's approximately 200 sessions, 35 had the phrase in their title.

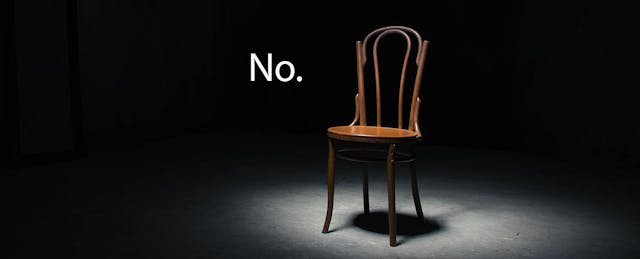

Competency-based learning (CBL) refers to the notion of allowing learners to acquire credits based on goals they hit rather than the amount of time they spend in a chair, affectionately referred to as “seat time.”

Yet while the spread of CBL has gained some momentum and popularity over the last few years, there are a number of roadblocks that schools, districts and states still face when attempting to move away from the “seat time” concept.

To help ease the stress of introducing competency-based learning into a new environment, EdSurge chatted with a few educators and researchers on the iNACOL floor to hear their tips and tricks for making the push for CBL—and likely any blended or personalized learning program, as well—all the more successful.

Tip #1: Let Teachers Lead the Charge

In many successful cases of CBL, teachers have been the ones to evangelize others, especially when they’ve implemented and seen what effective CBL looks like in practice. Kelly Brady, the current Director of Mastery Education for the Idaho State Department of Education who’s written about competency-based learning, is a prime example.

Before she moved up to the state level, Brady spent thirty years in Boise, Idaho teaching K-8 students in the classroom, in both private and public schools. During the last thirteen years of her teaching career when she worked in a gifted/talented program, Brady experimented with curriculum and instructional design that allowed students to progress at a flexible pace, based on their individual development. She recalls her favorite part of those lessons—Flow Day—in which students got to pursue passion projects tailored to their individual interests.

When Idaho Governor Butch Otter put together a task force in 2013 to decide the trajectory for improving the state’s public education system, what came out of those discussions was a decision to move towards mastery-based learning (a phrase describing a more general approach to competency-based learning). And who did he choose to lead it? None other than Brady herself.

“I did this all in my classroom,” she tells EdSurge, “So now, we’re outreaching and educating, and it helps that I understand what this could look like for any teacher, and any group of students.”

Tip #2: Loosen Up Roadblocks and Reconsider How Teacher Evaluations Look

According to Brady, certain policies and district requirements aren’t conducive to allowing CBL to flourish. “It’s a real problem when we fund schools by attendance, especially when that can look different if you aren’t judging students by ‘seat time,” she says. Luckily, in the state of Idaho, Brady and her team have started to create waivers to allow districts and schools to report how many students are hitting particular goals in a certain amount of time—rather than how many days those students have physically attended school.

But this is far from the only structure that hinders CBL from progressing. Take the process of teacher evaluations. Jeni Gotto, Executive Director of Teaching and Learning at Westminster Public Schools in Colorado, reports that in her district, they’ve gone from sporadic teacher evaluations to principal “Zone Walkthroughs” in and out of classrooms every single Thursday. Why? With the constant stream of feedback, teachers know more consistently how they can improve their CBL practices.

Additionally, principals “judge teachers on specific competencies” related to CBL, Gotto reports, and track it all on Westminster’s Empower learning management system—again, making it easier for the teacher to pinpoint what needs to be addressed. “Originally, we made assumptions that [teachers] would know what to do,” Gotto explains. “But we quickly realized they needed a lot of support, and that we needed a set of teacher ‘proficiency scales.’”

Tip #3: Educate Everyone on What Competency-Based Learning Looks Like

At the end of the day, CBL will touch every stakeholder in a district—not just the students and educators. And according to Tom Rooney, superintendent of Lindsay Unified School District, it's up to the school or district to educate parents, board members and the surrounding community on how CBL works. “In order to ensure learners progress, we have to bring along the adults. We have to answer that question of, what is the knowledge that the adults in a personalized system need to have?”

One group that often gets left out is the board members, Rooney says. This can make things particularly complicated when the board votes on allowances or policy changes that could either support or inhibit a CBL initiative. But there’s nothing with taking a little trip to other CBL districts to show them what’s possible, Rooney says. In fact, Idaho’s Kelly Brady agrees, sharing that she’s taken her team and representatives from districts to New Hampshire, where the state is leading a high school redesign project with CBL as the backbone. “It helps to have some inspiration,” Brady says.

Brady is also optimistic that with a little time, more districts and school will make the jump to CBL—if they take the right steps.

"It's just such a wonderful way to ease students along the learning process. They don't feel like they're in a rush—and that's good."