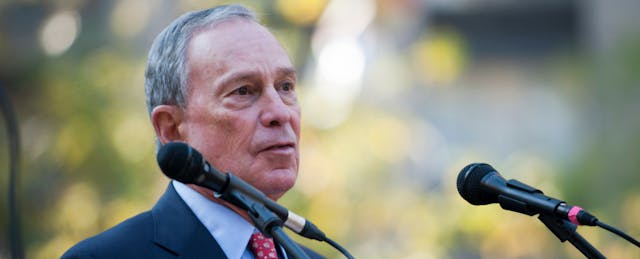

Ten years into his 12-year tenure as mayor of New York City, Michael Bloomberg and his then education chief, Joel Klein, kicked off a program that they hoped would transform education in the city by making schools “centers of innovation,” Bloomberg told the BBC back in 2011. The ambitions for New York City’s Innovation Zone (or iZone) were sweeping: By 2014, city leaders hoped it would be the catalyst for technologically enhanced personalized learning models throughout the district, encompassing 400 schools.

But it never hit that target, and now the vision has taken a U-turn under current Mayor Bill de Blasio. In 2013 the Gotham Gazette reported that the iZone had a budget of $47 million. Today that budget is $3.2 million, according to the New York City Department of Education (NYCDOE), a 93 percent decrease since 2013.

Steven Hodas, who served an iZone Director under Mayor Bloomberg, told EdSurge that in 2014, the center had a staff of 65 personnel working with more than 300 schools. The program is now run by 14 staff members, reports the NYCDOE. (Hodas left in 2014.) Exactly how many schools are actively engaged as 'iZone schools' is unclear: The NYCDOE press office disclosed that 50 schools abandoned the iZone’s iLearn program between 2015 and 2016 to develop their own blended and online learning materials or to use outside resources including Google Classroom, Schoology, or Canvas.

This is how programs end: Not with a bang but a whimper—and a shrinking budget.

Driving organizational change is enormously hard. This piece from Gallup, for instance, argues that 70 percent of the change initiatives undertaken by organizations in Singapore were “doomed to failure.” Given the decline of the iZone, many people in New York are wondering: What does it take to build education policy programs that are designed to last?

When the iZone was in its heyday, the center aimed to make it easier for schools to use new technology while piloting student-centered designs. The iZone360 program aimed to help participating school leaders reorganize everything from budgets to schedules to meet personalized learning needs. Described by some media outlets as a “splashy” program “ripping up the rule books,” the iZone’s unconventional approach was subject to scrutiny and constantly morphing. For example, a competition called the “Gap App Challenge” that invited startup companies to pitch their tools to iZone schools paved the way for a “Short Cycle Evaluation Challenge” that pairs public schools with edtech developers to test technology products.

However, Hodas dreamed of moving the iZone from a “fringe” activity to a district-wide phenomenon. He imagined a large district willing to take risks on new ideas. “We would have deepened the work that we started at the systems level. You only have so much force, so you want to apply it where it will have the greatest amount of change,” says Hodas in an interview with EdSurge. “If you change the way the district, state, federal government or foundations think, you affect a lot more schools.”

However, amidst constant leadership turnover and changes in city administration, the iZone never achieved Hodas’ vision.

Politics plays a huge role in education policy shifts, notes Hodas. “School districts are extremely political places,” he says. “Every administration has its favorite initiatives and people. If you’re not on the ‘good’ list, you become the unpopular kid in the school yard. Principals and administrators got pretty clear messages about whether it was ‘cool’ to work with the iZone or not.”

Frederick Hess, the director of education policy at the American Enterprise Institute, also believes that politics play a significant role in education innovation initiatives and changes.

“If you’re elected mayor and you spend your four years working really hard on the previous person’s initiatives, the media ends up talking about how you are a do-nothing mayor. This encourages [politicians] to shift to something they can say: ‘This is my initiative,’” Hess told EdSurge.

Hess noted that it is important to consider a politician’s inner circle and who has the politician's ear. When political administrations change, “the neighborhoods they are focusing on are different, and the people they trust or get advice from are different. They are getting different information about what good innovation or edtech is,” he explains. According to him, changes to a program’s funding and significance could also come from key influencers like New York City School Chancellor Carmen Fariña—whom de Blasio keeps close during every school initiative announcement.

The Cost of Political Shuffling

When political vehicles change course on education initiatives, there are consequences for everyone involved.

“Frequently if employees started under Bloomberg and they are people that he liked and trusted, by definition those are people who de Blasio is going to be suspicious of,” says Hess. He notes that personnel in charge of the former administration’s programs, and the students and families served by those programs, are often the ones who get lost in the political churns. “One of the things that make for great schools and great learning is the ability to build cultures and pyramid expertise,” says Hess. “The turmoil of the political process, even if politicians are making the right decisions, has a cost in terms of uncertainty and discombobulation."

Does that mean every administration’s big program is bound to wind down? Hess is not optimistic: “There’s no guarantee that a policy will be in place ten years after a politician leaves office,” he warns.

There are, however, three things politicians can do to make their programs more sustainable, Hess observes. First and foremost, families need to feel so deeply invested in the educational innovation that they’re willing to fight for it. Second, the innovation needs bipartisan appeal so that when the next administration comes in, the newly elected leaders won’t see the program as belonging to the “other” side.

Third, the politicians and the employees who run the program must demonstrate that it works. “One of the National Institute of Health’s great advantages is that it can point to a long laundry list of ‘wins’ that have been good for people's lives,” said Hess. “The more you can make a case that your work is good for families and good for kids, the harder it is for a politician to explain to a journalist why they are going to discontinue it,” he added.

Unfortunately for Bloomberg, the Innovation Zone doesn’t appear to have been built in the sustainable manner that Hess described. Nevertheless, city bureaucrats still see value in what the iZone was and what is left of the project. “The iZone continues to be a critical part of supporting innovation across our schools—through the diffusion of its work and ideas across schools and initiatives,” the department communicated to EdSurge in a statement. Several of the ideas championed by the iZone, including blended learning and design thinking, have become regular features of NYC schools. In addition, early iZone work in computer science education and innovative classroom practices have also supported the Computer Science for All goal.

Although support for the iZone has waned, NYCDOE officials insist the program is “supporting the next wave of innovation.” The latest initiative with a catchy acronym is PROSE (short for Progressive Redesign Opportunity for Schools of Excellence), which launched in 2014 after de Blasio took office. It claims to enjoy the support of the city teacher’s union, allowing schools with a “record of success” to bend the city contract rules to experiment with personalized and blended learning ideas. Yet whether these efforts are sustainable, or merely the next pet project whose support depends on political tides, remains to be seen.