Why does personalized learning, ironically, feel so impersonal?

Personalized learning, in its broadest application, suggests tailoring instruction to meet the needs, strengths and interests of each learner. Great teachers already do that everyday—with or without technology. It should be a goal both broad and laudable enough to unite teachers and technologists, parents and policymakers.

Yet there is clearly a gap between how educators and entrepreneurs perceive “personalized learning” and many other technology-infused terms in education. A revealing flashpoint happened earlier this month, when a story about “personalized learning” published by the National Education Association, the biggest teachers’ union in the country, drew more than 70 comments—mostly negative and a few even inflammatory. One of the more measured reactions reads:

There is NOTHING “personal” about personalized learning! It robs students of all individuality, creativity, and sociability. Kids see enough technology in their day without adding to it at school. I've worked with kids in these “personalized” lessons before. They're fancy computerized worksheets—and bad worksheets—focusing on minutiae and no authentic learning.

I will fight “personalized learning” until my dying day. It takes away teachers’ and students’ humanity.

The backlash, in the words of Education Week’s Benjamin Herold, “echoes previous battles among various teachers’ union factions over highly politicized issues such as the Common Core State Standards and standardized testing.”

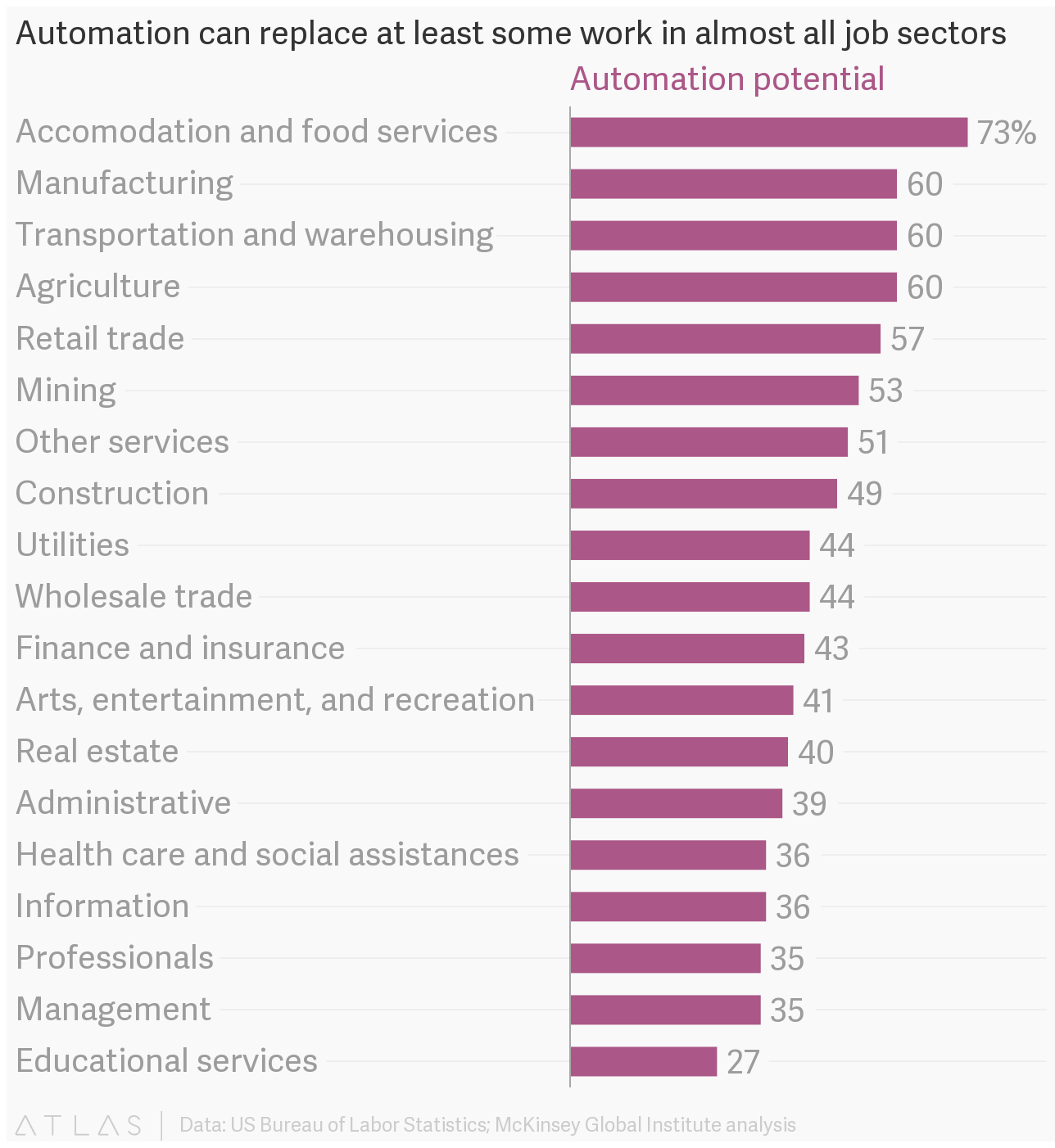

Few education entrepreneurs today would suggest that technology should or will replace the teacher. (In fact, Quartz suggests that education services are the least likely to be automated of 19 job sectors, based on data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and McKinsey Global Institute.) But clearly many doubt the for-profit sector’s intentions.

Technology companies—in all industries—make users anxious when they describe their work with the vagueness of a magician. Public misconceptions linger, in part, due to a deliberate lack of communication and transparency. Those making “personalized,” “adaptive” or other technology tools fuel that nervousness when they fail to answer a basic question that every child is raised and taught to ask in school: How does it work?

Rather than answering the question, lazy entrepreneurs too frequently offer vacuous references to companies like Amazon and Netflix. They assume that parents, educators and yes, reporters will give learning technologies the same benefit of the doubt that we afford to movie or online shopping recommendation engines. This is a mistake. Black-box software, as OER pioneer and Lumen Learning’s Chief Academic Officer, David Wiley writes, “reduce all the richness and complexity of deciding what a learner should be doing to—sometimes literally— a ‘Next’ button.”

Yes, that feels rather heartless and impersonal.

Why should I, or any teacher, trust secret algorithms to suggest what people “like” me, or any student, might need? (To even claim that people are “like” me or you based on browsing patterns can feel more presumptuous than personalized.) If we are asked to use education technology without fully understanding how it works, then it is fair to worry that technology—not the human—is driving the learning experience.

Even more frustrating are those who wantonly brand their company as the “Netflix (or the equivalent) for education.” Many entrepreneurs frequently claim they are adapting tactics from other technology verticals into education. Let’s, for instance, take how companies like Google and Facebook “personalize” a user’s web browsing experience through search results, ads and content—and then apply that to instructional experiences.

These analogies are fraught with risk because big technology companies haven’t earned unconditional public trust. Facebook got slapped for discreetly tinkering with users’ news feeds for a controversial study on emotional manipulation. It took a lawsuit to get Google to stop scanning students’ emails. (Tip: Companies that once touted themselves as the “Uber for learning” would be wise to shed that analogy.)

That discomfort gets amped up when the people who literally invented the technologies, such as Mark Zuckerberg, become enthusiastic proponents of personalized learning. In other words, when the Facebook CEO champions “personalized learning” (as he did in September 2015), the controversies that have dogged Facebook over data mining, privacy and other issues are passed along to the education sector.

Unfortunately such public perception issues, including fixations on affiliations rather than on what matters, too often overshadow the tireless efforts of educators, researchers and, yes, even entrepreneurs who devote everyday to figuring out what works best for students.

By no means are these problems unique to “personalized,” “adaptive,” “blended” or the education trend of the moment. Looming on the horizon are efforts to apply machine learning and artificial intelligence to education—ideas that are even more opaque and obscure. Entrepreneurs should expect more hackles and doubts if they keep these technologies a mystery.

Great education encourages and empowers children to ask and figure out how something works. The adults who build tools to support this goal ought to hold themselves to that standard as well.