The University of Texas at San Antonio has more than 2 million titles in its library system, and lately it’s been building a collection that most students—and future teachers—might not even know exists yet.

A small but growing library of augmented reality books, consisting of 25 children’s titles, is part of a research partnership between UTSA Libraries and the College of Education and Human Development (COEHD). They range in subject from astronomy, to dinosaurs, and even cardboard bedtime stories for infants.

The purpose of the collection is threefold: to allow teachers in their preparation program experiment with AR books, to study the effectiveness of the texts in an educational setting, and to offer the country's first augmented reality library.

Ilna Colemere, an instructional technology coordinator for COEHD, is heading up the project. She says she grew interested in augmented reality books after conducting research on affordable virtual reality materials for teachers.

“I looked for education technology trends and tools, and I saw teachers referencing AR books but there was no depth of context on how they work,” says Colemere.

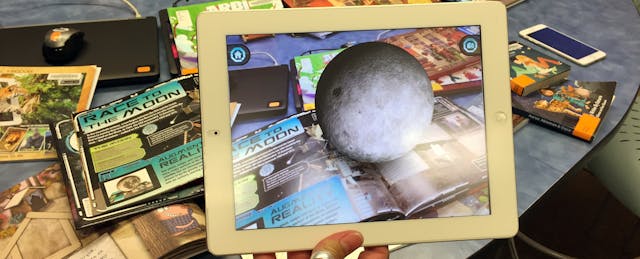

The best way to envision these titles is picture a digital take on an old classic: pop-up books. Using an app on an iPad or other tablets, readers hover over a book to see and interact with images that appear in 3D. For instance, students can crank the heat up on a virtual bunsen burner in a chemistry book, or feed a lion in a story about animal kingdoms.

Colemere and Rachel Cannady, an education librarian for COEHD, began collecting AR books this spring and say they have purchased a large portion of AR children’s books available to purchase in the U.S. The books are now part of COEHD’s “edtech library,” a collection of tools that future teachers can use during their in-classroom training, including STEM kits, clickers, Google Glass and Apple TVs.

For each of the tools available, the teachers must do a workshop with Colemere on how to use the devices. “When teachers in our program go to their practicum, they become change agents. This is where they should test out technology—at the university,” says Cannady, a former English teacher.

On July 12, Colemere will introduce the AR books to COEHD’s current class of clinical teachers—those completing an in-classroom portion of the teacher preparation program—who can borrow the books from the UTSA John Peace Library to use with students this fall. Colemere and Cannady hope to analyze teacher feedback about the uses and effectiveness of augmented reality books alongside Dr. Mary Elizabeth Green, a faculty member at Texas A&M Kingsville who has published some of the only existing research on augmented reality books.

“I think the teachers will be excited, and they will come up with so many ways to use these books,” says Colemere. “That might push publishers to make more content-driven and less entertainment-driven books that support specific standards.”

Some of the augmented books in UTSA’s collection also have capabilities to be read aloud. Colemere says this could be useful for some students with learning disabilities. “It makes the books come alive in a different way,” she says. “People think these are toys, but if used the right way they can be quite powerful.”

For all their curiosity, Cannady and Colemere both have plenty of concerns about augmented reality books, and aren’t convinced that what exists today will improve education any time soon. In addition to the sheer lack of options available, the books do not have reading levels and vary widely in terms of their usefulness. (One book, for example, had an AR scene which covers up the text, making it impossible to read the book from the device.)

Another problem they have heard from teachers is that AR is distracting for some students who won’t read the text but instead skim the book with a device looking for pages where the AR is activated. And for some books created outside the U.S., Colemere says there aren’t even apps available to use in the country.

Librarians and researchers at COEHD hope to expand the AR library, but for now the options remain limited. AR books have yet to expand into literature or higher grade level materials (you won’t yet find an AR version of “Of Mice and Men”) but perhaps textbooks are what’s next to come. Colemere says a high school biology e-book with AR capabilities already exists, and with apps like Aurasma, which allows users to create their own augmented reality simulations, she believes students might be the ones to create more AR books before big publishers do.