Blaine is a student in a suburban town. He wakes up at 7 am and brushes his teeth before wolfing down a bowl of cereal. After putting on his high-top sneakers, he races out the door to the street corner, where he waits for the school bus.

As he steps on the yellow ride, Blaine panics. Did he forget his school-issued RFID badge that he has to tap so that the district can have a record of him getting picked up? Whew, it’s at the bottom of his backpack.

While Blaine is a fictional student, the technology that’s tracking him is real, and actually in use in some school systems, part of a growing set of tools that leave data trails about students throughout the day. These days, fingerprint scanners and cameras are regular parts of school life—on the ceilings watching students walk, and on their laptops analyzing their facial expressions. The tools could yield benefits for safety, performance development and security, but they also raise thorny security and privacy issues.

“Imagine a breach like the Equifax one we just had, but occurring with students’ browsing history, the search strings of the school counselor or geolocation of all students in the school,” says privacy blogger Bill Fitzgerald, noting the risks companies are taking while gathering sensitive information on students.

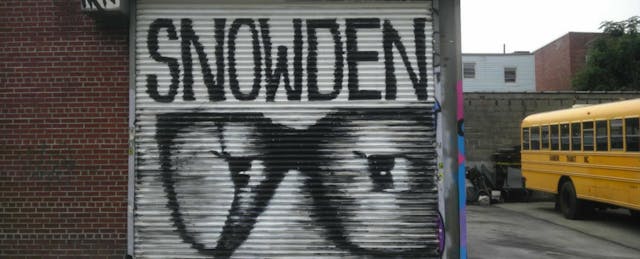

The darker side of today’s Big Data world was exposed a few years ago by Edward Snowden, the former Central Intelligence Agency subcontractor turned leaker and whistleblower, who raised concerns about US government surveillance and shaped the national conversation on privacy and security. In some ways the tools that parents, teachers and administrators have opted for include surveillance capabilities that turn into schools into Snowden’s worst nightmare.

Let’s follow Blaine throughout the rest of the day—and learn how his experiences mirror what happens in real life.

The bus drops Blaine and his classmates off at 8:30 am. But before he can enter the school building, he has to pass through a metal detector.

In 2016 ProPublica reported that 236 schools in New York City required students to go through some sort of scanner to enter schools. In Los Angeles, all public high school students have grown up with metal detectors and random searches when entering school buildings. Scanners consist of metal detectors, X-ray machines and hand wands. The use of these tools have been criticized for disproportionate use in environments with large Hispanic and Black populations.

Blaine is almost late for class, so he jogs—but not too fast since he knows there are cameras in the hallway, watching him.

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, in 2013-14 school year, an average of 75 percent of public schools reported using security cameras to monitor their buildings.

Here is a little-known-fact, FERPA laws regarding a parent's right to access video footage is unclear. There have been a few court cases where judges ruled that video footage obtained by school officials or other district contractors were not considered education records and were, therefore, not the right of students or parents to access.

Blaine scans his ID and enters the classroom. He is two minutes late. An automated detention slip is printed out for him. The teacher, who has already begun to brief the class on the day’s assignment, doesn’t notice.

In 2013, HeroK12 began offering educators an opportunity to collect and analyze student behavior data. Through its software, every tardy and dress code violation is recorded, stored and analyzed on individual, class and school levels. The violations and consequences are easily tallied with automated responses, and teachers, administrators and students can view the data. HeroK12 is currently used in more than 650 schools around the United States. Other similar technologies include Kickboard and LiveSchool.

And cameras have moved from hallways to classrooms, with technology and security companies actively marketing them to schools. Extreme Networks’ Camera AP 3916i solution, a tech company that actively markets cameras to schools, recently released a survey on video surveillance in classrooms, noting benefits such as preventing theft, vandalism of classroom materials and reducing cheating.

Blaine’s district provides every student with a computer, so he opens his laptop to start his work.

As soon as a school-provided laptop is opened, there are multiple ways students can be surveilled. In 2000 federal legislation required schools to filter content students accessed online. Since that time, monitoring online behaviors has become even more extensive.

GoGuardian, a web-filtering tool, just announced an upgrade to its technology that relies on artificial intelligence to scan every page a student accesses on school networks or devices. The company promotes this as an opportunity teachers to detect potential cases of pornographic content and language that could indicate possible desire to harm oneself. The product is currently in use by 2,400 school districts serving more than 4 million students.

Other filtering tools include companies such as BASE Education in Colorado with features that capture all student text—even after it is deleted. Impero, another filtering software company, boasts capabilities to detect radicalized children and prevent threats of terrorism by looking for keywords such as ”YODO” (you only die once).

There are few restrictions on the way schools or law enforcement officials can access the camera on a student’s computer. In a recent report by ACLU Rhode Island, the organization noted several incidents of school staff taking photos of students in and out of school without their knowledge through webcams on school-provided laptops. The opening of the report featured an image of a student sleeping in his bed at home, taken through his device by school officials without his knowledge. In the report, ACLU notes that 22 districts in Rhode Island require parents to acknowledge that there is no expectation of privacy when using computers that are part of their one-to-one program.

Other camera functions such as SensorStar’s EngageSense claim the ability to use facial-recognition technologies to track student engagement online; the product is still in the research-and-development phase. Companies have also shown interest in developing eye-tracking technologies to improve online reading habits.

During lunch, Blaine pays for his food using a fingerprint scanner, which recognizes him and deducts the amount from his account.

Apple’s new iPhone might have replaced fingerprint scanners with facial recognition, but that doesn’t mean schools have to follow suit. Companies such as PushCoin offer cafeteria workers speedy lunch delivery and data as the software records everything a student eats when they pay by fingerprint.

At the lunch table, Blaine scrolls through his smartphone, liking and commenting on a few videos and photos posted by his friends.

Back in June, PBS and Education Week released a report about social media monitoring in schools. The profiled school district, Dysart Unified in Arizona, employs school resource officers to monitor social-media activity. One such officer explained to reporter Lisa Stark that she has “busted” everything from marijuana brownies on campus to possible student protest by monitoring social-media accounts. Districts have also been known to monitor student activity online through firms such as Geo Listening, and by closely watching any mention of the school or district online.

Blaine is only halfway through the day and has been monitored in over 10 different ways. The data collected through these services have information on everything from Blaine’s eating habits to how fast he is reading through an assignment online. His story begs the question, can schools surveille students into safety or improved academic performance?

Many educators and software designers—touting adaptable technologies—say, yes. They have put their money on algorithms and artificial intelligence that depend on large amounts of student data to be effective. They hope that technology can offer the classroom insights and data that humans cannot capture.

However, privacy experts fear the cyber-security risks associated with adaptable technology’s rise to the top is akin to the popular meme of a dog sitting with a cup of coffee saying, “This is Fine,” in a room that is on fire.

Doug Levin, an industry expert who has been carefully tracking data breaches in the K-12 school districts, echoes Fitzgerald’s concern, saying, “It is incredibly hard for even the most tech-savvy companies to secure potentially valuable information. It’s not a question of if a breach will happen, it is sort of like when and how do I respond.” Since 2016 he has identified more than 200 cybersecurity related incidents in schools.

Levin also takes issue with the algorithmic method in which technology tracks and responds to student behavior. “I understand why these tracking technologies might be appealing to some administrators. There are ways it can save students. But it is a very slippery slope down to Minority Report,” Levin explains. “You are making predictions like, ‘Johnny has a 95 percent chance that he is going to commit plagiarism. He hasn’t done it yet, but we will go in there and intervene now.’ That’s a great startup idea. We can help kids before they even know they need help.”

For Fitzgerald, the question goes beyond the seemingly dystopian realities to a philosophical debate about the roles of humans and machines.

“For me, the question is, what does it mean for a student to get help, not because someone actually cares about them—but because they fit into an algorithm?”