In 2015, the city of Albuquerque declared that instead of celebrating Columbus Day on the second Monday of October, it would commemorate Indigenous Peoples’ Day. Last year, Santa Fe followed suit, and just recently, Los Angeles announced that it would add Indigenous Peoples’ Day to its municipal calendar as well.

These changes provide educators, especially those in areas with large Native populations, both a challenge and an opportunity. As teachers at South Valley Preparatory School, an Albuquerque middle school, we’re accustomed to teaching students history from multiple perspectives.

Then and Now

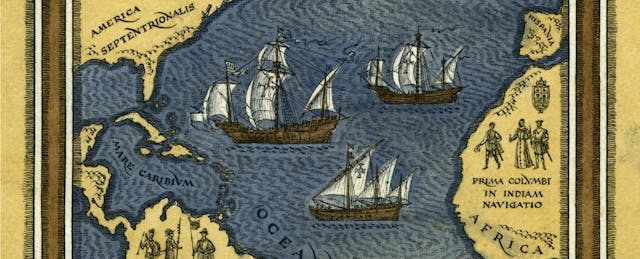

For me—Robyn—there’s a big difference between how I learned about Columbus, growing up in the 1970s and ‘80s in Southern California, and how I teach about Columbus and other early Spanish explorers. The narrative I was taught told us that Columbus “discovered the Americas,” and that the Spanish “civilized” an uncivilized world.

New Mexico has a vibrant, thriving Native population composed of many tribes who have a strong cultural presence. Talk of “Columbus Day” has not been a part of my experience in this state since I arrived in 1996. My first job in New Mexico was on the Navajo reservation, so I am sure you can imagine that our focus wasn’t on celebrating Columbus or other colonizers.

Today, in my seventh-grade humanities class, we look at the perspectives of the Taino of Hispaniola and the children aboard Columbus’ ships. We learn about the rich cultures that existed in the areas the Spanish first encountered, and imagine we are in their shoes. We discuss the notion of a hero versus a villain and how those labels vary according to whose perspective one is taking. As our school has made the Aztecs our mascot, we are sure to learn about the strength, architectural prowess and dignity of this early American civilization.

Columbus gets a couple of lessons of discussion and writing and we continue on to Cortez, Pizarro and others. At the same time, we consistently recognize that there is an alternative narrative to Columbus Day. How could we not?

We try to introduce the idea of critical thinking in all of our classrooms. We discuss fake news just as we discuss historical biases that have always been at play. For example, when learning about Jamestown and the British colony's contact with Pocahontas and her tribe, we read a primary source document from Powhatan Chief Crazy Horse, who debunks Disney's portrayal of Pocahontas and her relationship with John Smith.

Thanks in part to my three years of teaching on the Navajo reservation, I feel a heightened awareness and interest in “getting it right” when it comes to teaching about the history of our country. Also, I usually have one or two Native students who end up at our little South Valley school, and it is such a pleasure to have someone who can share insights and pride in their culture and traditions with the non-Native kids at our school.

There are two resources that I find invaluable when teaching history. One is a book called We Were There, Too! Young People in American History.This book is loaded with gems (mostly primary source documents). Another is the poetry template for an “I Am” poem. I use this to facilitate assessing whether my students truly “got it” when it comes to the perspective of peoples of the past. Through their poetry, it is easy to see if they have learned much more than dates and names.

Sparking Real Discussions

Indigenous Peoples’ Day has never been formally taught at our school, but maybe this year in Jamie’s enrichment classes it will turn into a great Socratic seminar discussion. In our Socratic seminars, we give the students different articles and ask them whose point of view they are written from, and have them look for hints of bias.

To spark these discussions, our teachers use various resources that they research on their own, including videos and primary sources from our literacy platform ThinkCERCA.

For example, I still teach about Columbus, but from the perspectives of the oppressor and the oppressed. I present the question, “How can this be the same events, but different stories?”

For so long, history has been taught from point of view of the oppressors, not the oppressed. In our school, we are always trying to give the past a voice that has a 360-degree perspective, not just a 90-degree view. That’s something that can resonate with every student.