Rebecca Stout remembers the time she got a call from Saudi Arabia at midnight from one of her online students looking for help on an assignment.

It was just one example of how she—and many online instructors—feel like they must be always on call when they teach an online course. At the 2017 OLC Accelerate conference in Orlando on Wednesday, Stout, the lead faculty for sociology within the general education program at Colorado Technical University, talked about burnout among online, adjunct instructors, and how to recognize it and prevent it.

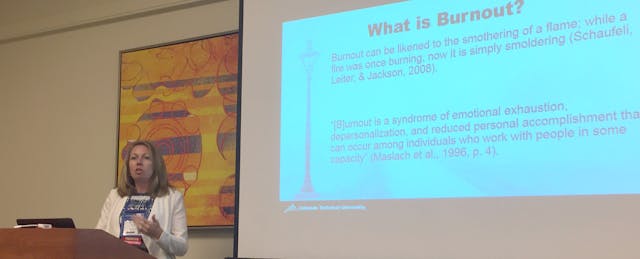

Stout researches burnout and oversees around twenty adjuncts who teach online. She said she’s cognizant of how easily the online teaching environment can cause burnout, which the Mayo Clinic describes as a “special type of job stress—a state of physical, emotional or mental exhaustion combined with doubts about your competence and the value of your work.” Stout said because online education has “grown exponentially,” so have the number of adjuncts charged with such classes.

“These online positions work remotely, it’s very appealing,” Stout said. “People think, ‘Oh, I can work in my pajamas any time of day, with my kid at my feet watching cartoons.’ Well, we know the reality: it’s very difficult to do that, and that’s not really what online teaching is.”

Teaching online means being away from a work site and away from the physical and moral support that instructors get teaching face-to-face courses, Stout said. Online teachers often begin with a more difficult hurdle to overcome.

“A lot of us went to a traditional university… where we were taught in a classroom situation,” Stout explained. “And then all the sudden we’re teaching online. But we are not given the same training that people who are taught face-to-face do. If you’re in graduate school, you often work as a teaching assistant, you’re under a mentoring program, you’re taught to be a teacher. Online teaching is not necessarily the same.”

However, a lot of postsecondary institutions have not implemented a specific strategy to help prepare faculty to teach online.

“Online teachers often feel like they’re on an island,” Stout said. “They’re in their pajamas—sure, that’s appealing—but they’re also alone.”

She also pointed out that online teachers need to overcome negative perceptions about what they do, such as the notion that teaching online isn’t real teaching.

There’s a correlation between burnout and health-care costs, Stout said. But burnout also leads to low employee morale, a reduced likelihood that an instructor will stick with an institution and a lesser likelihood that an instructor will be engaged. Disengaged instructors are less likely to care about their students. And what’s more, a burnout might result in an instructor objectifying students.

“That person is no longer a person, it’s just a name on a screen,” Stout said.

Stout told the audience about the Maslach Burnout Inventory test, which quantifies burnout into three subscales: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and (reduced) personal achievement. It’s the most-commonly used instrument to measure burnout, she said, and there’s even one that’s tailored to measure burnout among educators.

The research on burnout in online higher education professionals is “very conflicting.” Although it’s known that online educators experience burnout, there hasn’t been a firm conclusion on exactly how and to what extent burnout exists among online instructors.

Stout did her own study to explore burnout and its prevalence among a group of online higher education instructors. It was not done at Colorado Technical University, but at a different proprietary, post secondary institution that she declined to name for privacy reasons. She thinks it could be generalized to similar institutions where there are high levels of adjuncts who are given “turn-key” courses where they don’t create the content, but are taught to deliver it. She found that those in her study did experience moderate levels of burnout.

“And if they’re experiencing burnout, that’s going to be a problem,” Stout said. “We have to be aware of what’s causing it and why.”

There are several signs of burnout. Stout pointed to having a short fuse, physical problems, a negative attitude, apathy, self-neglect, lack of interest in social activities, exhaustion and escapist behavior.

“Teaching is daunting,” she said. “Online teaching in particular is very hard. It happens 24 hours a day, seven days a week, and you never get a day off.”

To prevent burnout, Stout said supervisors have to encourage faculty members to take care of themselves, and let them know that it’s ok to unplug and spend time with family and to unplug their phone at night—so they don’t get a call from Saudi Arabia.

Stout said supervisors should also encourage faculty to nurture relationships with students.

Stout told the audience that the opposite of burnout is engagement.

“So really as an institution, as administrators, as lead faculty, or whichever position you take, you have to help create that engagement.”