“What state is south of Washington?” I asked the fifth grader beside me. His class was playing an online puzzle game and attempting to fit the U.S. states together. The student just shrugged. Another selected the piece for Maine without knowing where to place it on the map. When I hinted that Maine was in the Northeast, she moved the piece to the Midwest.

These observations at a school in southeastern Washington reminded me of my own experience teaching fourth and fifth graders in Arizona. My students memorized state names and capitals, but could not locate them on a map. Many were unaware of the differences between a state, a country, and a continent. And it's not only kids who lack geoliteracy—adults often have limited knowledge as well. Too many of the pre-service teachers who I teach today also found this puzzle to be a challenge.

With GPS in our cars and Google Map on our phones, we no longer navigate for ourselves. While these tools often (but not always) save us from getting lost, they do little to encourage us to learn our way around the city, the country or the world. What happens when our citizens, or worse, our leaders, lack this fundamental understanding? During the 2016 presidential debates, Libertarian candidate Gary Johnson asked, “What is Aleppo?” Addressing African leaders at the U.N. last fall, President Trump referred to the non-existent country of “Nambia” twice. If that's acceptable, why should 5th graders care?

Connecting the Dots

Geoliteracy is more than pinpointing locations on a globe. It is the ability to connect them with wider issues. How can we gauge global climate change without a mental map of normal temperatures? Or assess human encroachment on animal habitats without knowing their environmental range? How can we understand the plight of immigrants or refugees without understanding the places from which they came? In a politicized era of “alternative facts,” children (and adults) need spatial reasoning skills more than ever to critically analyze the news and their personal world.

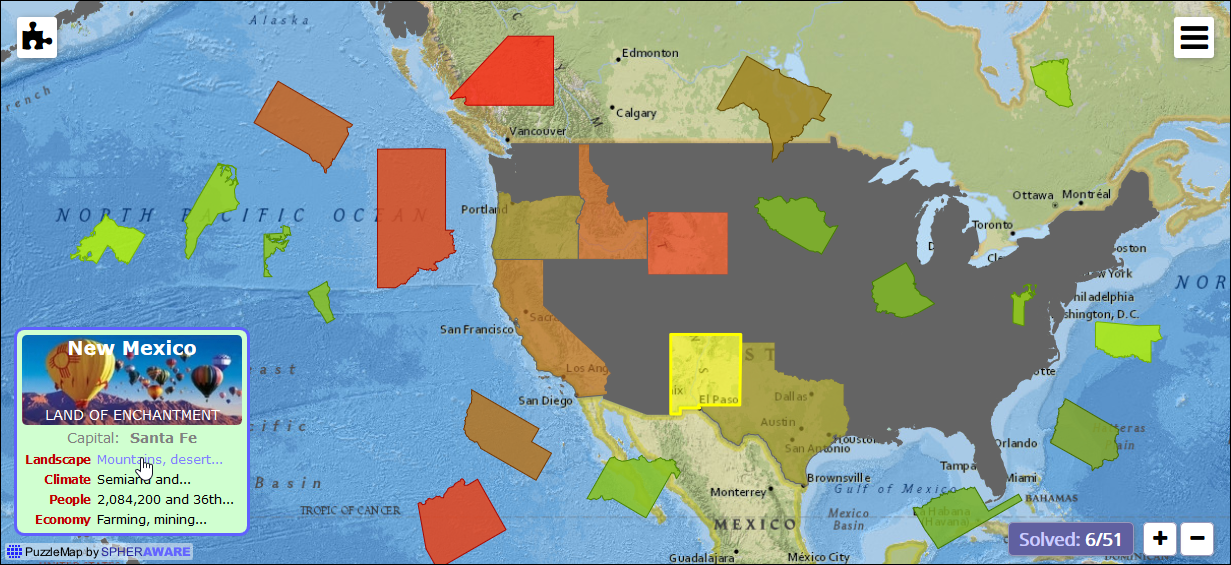

A growing concern for these issues inspired Fred Newcomer, CEO of SpherAware, to develop a program that turns online web maps into interactive puzzles. It's called PuzzleMap. This software engineer is also my father. As a kid, my dad’s passion for geography and the earth’s beauty led to memorable camping trips, star-gazing sessions and important learning opportunities like reading a road map during car trips. Now, as a teacher-educator and researcher, I’ve had the amazing opportunity to partner with him to take his passion into the K-12 classroom.

This past fall, my father and I put PuzzleMap to the test in three different classrooms in the Tri-Cities area in southeastern Washington. Together with my Washington State University colleague, Jonah Firestone, we created a special puzzle of the U.S. states tailored to a fifth-grade social studies curriculum. We used 3 regional variations as well as the entire puzzle to encourage and support students during their regular social studies unit on the geography of America.

We hoped the tool would put students in charge of their learning. When a puzzle is first loaded, the subject area is completely obscured so that no identifiers or internal details are visible. The pieces are scattered randomly across the screen and must be moved and rotated into their correct location. An interactive clue window, appearing each time a piece is selected, provides a rich informational context.

These text and image clues can also link to external resources, zoom to a specific location or even play sounds. As each piece is successfully placed, the background map is magically revealed. In addition, each state in our USA puzzle remains color-coded according to its average annual precipitation, resulting in an interactive choropleth and another teaching opportunity.

To measure PuzzleMap's effectiveness, we created a pre- and post-multiple-choice assessment of our clues about the climate, landscape, economy and people of America. The questions reflected three categories: Conceptual (state-specific attributes), topological (states’ location and relationship to each other) and spatial (involving visual recognition of state shapes). The assessment also encouraged deductive reasoning. For example, "A Southwestern tribe called The Hopi live in which of the following states?" is easy to answer once a student determines that only one answer choice is in the Southwest.

We found that PuzzleMap has great potential for improving geoliteracy. Students who used it in conjunction with their social studies curriculum, or as a stand-alone resource, showed statistically significant growth, with test averages increasing by 12 and 8.4 percent, respectively. There was also significant correlation between puzzle completion proficiency and post-assessment scores. The more proficient students became at manipulating the pieces, the better they did on the post-assessment.

As tomorrow’s decision-makers, our children must be able to think critically about our interconnected world and see how actions in one place have profound consequences elsewhere. These skills are important for being successful in school and for becoming responsible global citizens. Our planet’s future rests in our children’s hands. They need the knowledge, opportunity and best tools we can provide to prepare them for the task at hand.