When she was in the classroom, Jenny Herrera remembers feeling resentful whenever the school principal would email teachers telling them they needed to stay after school to give feedback to edtech companies. What they got in return? Muffins.

“I don’t think that is ethical,” Herrera, now the Senior Director of Strategy and Operations at ProjectEd, told the audience at a recent panel session at the SXSW EDU conference in Austin. “You’re not going to say ‘no’ to your boss. Teachers are naturally people pleasing, and you care, but it does not seem fair when we all know that teachers’ time is so precious, to voluntold them for things.”

The ethics of teachers advising and working with edtech companies received a lot of attention when the New York Times published a piece on the subject last fall. Unsurprisingly, the panelists brought up the article—and their thoughts on the controversy.

Pilot Programs

Nadia Williams, a digital coach for Georgia’s Cobb County School District, said that when it comes to pilot programs, the ethics depend on who is initiating the product testing. In general, top-down mandates to test products are taxing on teachers’ time and provide few rewards, making them somewhat burdenous.

She mentioned a school district in Maryland, where a friend of hers works. When that district was evaluating learning management systems, it contracted with the companies it had “whittled it down to” and had pilot schools go through the long process of testing different platforms.

There have been several pilot programs with technologies for use throughout her own school district, Williams said. But, it’s a “pretty big district,” and implementing a tool system-wide requires making sure it works. The better option is to give teachers more control over which products they try out in the classroom.

“I think it’s great when teachers are driving that conversation and district personnel are helping drive that conversation as well,” Williams said. “However, we do get into some gray area when you have an admin putting teachers on the spot like that.”

Asking teachers for their input at the pilot stage is helpful, Herrera said, but the process should really start earlier. As someone who advises edtech companies, she thinks by the time a company gets to the pilot stage, they’ve spent a lot of time and money developing a product that schools “might not want.”

“It’s just not a good use of your resources,” Herrera said, adding that involving teachers from the start can actually save companies money in the long run as they figure out the problems their tool does (and does not) solve for schools. “So from a company side, pilots can work, but I think it needs to happen much earlier.”

Overall, the consensus from panelists and the audience, when polled by show of hands, was that vendor-educator relationships are above-board, given appropriate transparency measures. “We are all pretty much in agreement that teachers, when they’re being used for their time, deserve to be paid,” Williams said.

Are Teachers Too Tech Isolated from What’s Happening in Tech?

Mark Phillips is the founder of HireEducation, an edtech recruiting firm, and GigEd, a platform where teachers can find short-term “gigs” at edtech companies, and get paid by those companies. He said he’s “all in favor” of exchanging money between teachers and companies in order to avoid companies developing products in a vacuum and selling them to administrators, forcing classroom teachers to use a product that has “no relevance” to them.

But he believes transactions between edtech companies and teachers need to be both transparent and regulated.

Phillips, however, doesn’t think the question of ethics pertains only to getting teacher input on a product. He referenced the New York Times article, which discussed teachers working as company ambassadors, a relationship he described as “effectively selling” the company to other teachers, district staff and sometimes to parents and students—a relationship he thought could be mutually beneficial to classrooms and vendors, but must be mandatory for teachers to disclose, he later clarified to EdSurge. He added that, even then, abuses could happen.

Phillips also told the audience that some teachers—even talented ones—are “pretty isolated” in regard to what’s happening with technology. He said there are tools that his wife, who is a teacher, has never encountered because “she’s in the classroom not using tools all the time.”

“So I believe there is also a little bit of that Steve Jobs thing going on, where people need to be told what they need,” Phillips said. “I think there has to be a balance.”

Williams, however, said Phillips’s statement suggests that educators aren’t as savvy as they can be. She said it’s likely for professionals in any field to stick to what they already do and know, but there are teachers like herself who go out and find tools and resources for their classroom. But while she agreed that there are many teachers who don’t do that, she pointed out that they weren’t going to be “in this room” or seeking opportunities like ambassador programs.

Teachers Versus Sports Figures

An audience member submitted a question asking why teacher’s ethics would be different from anyone else’s ethics, such as sports figures and movie stars.

Williams said she sees some huge differences there, although she doesn’t agree that they should exist. Celebrities have managers, and operate “as a business of one in many entities.” The government doesn’t regulate what LeBron James can say regarding his shoes, nor does anyone question the ethics involved with him signing a sneaker deal.

However, she continued, educators face ethical questions based on what might be in their contracts, districts and certification status.

Herrera said she thinks teachers at private and charter schools have more “leeway to do things” around piloting products and connecting with companies, adding that there are “amazing examples just from lack of red tape.”

Phillips, however, said even in cases with private schools and charters, there’s still the question of influence, and educators are adults with responsibility over kids. But again, he’s not against vendor-educator relationships so long as they’re regulated.

“I would argue that there is a market force, and there always should be a place for that, it just needs to be really transparent,” Phillips said.

Williams brought up perception issues that come along with managing government funds.

“Sometimes perception becomes a new reality, and it’s not actually what went down.”

The Future

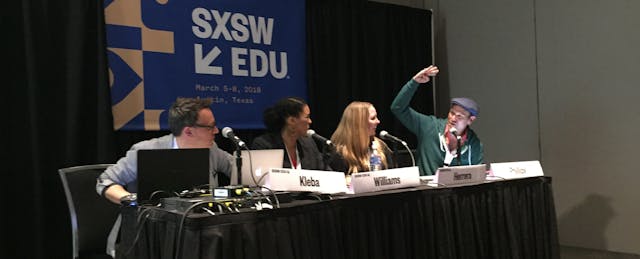

The moderator, Michael Kleba, an English and theater teacher currently on sabbatical to run DegreeCast, a college search engine tool, asked the panelists for their “most daring prediction” for what teacher-industry partnerships could accomplish in the next five years.

While his financial future depends on his wife’s teacher pension, Phillips said it also restricts where they can live, where she can work and her ability to choose to leave the classroom for a couple of years to work on a book and then return.

Herrera cited her friend, who won teacher of the year in North Carolina, as an example of systems and protocols already in place for educators. Her friend was “on loan” to the state’s Department of Public Instruction for a year. Herrera thinks something similar should be in place for teachers who are passionate about digital or non-digital products and want to take a year of sabbatical to help train other educators, research or work for an edtech company, she later clarified to EdSurge.

She also wants to see a level system for teachers, like some other professions have. “You don’t go in our first day as the chief surgeon, except in teaching you do.” Having levels would improve the profession, and additionally, as teachers climb up in rank, they can get flexibility in their schedule, such as having two periods free that they can use to help make a product better.

Williams, on the other hand, wants to see “more teacherpreneurship,” meaning educators shouldn’t just be consulting companies about products; they should be creating those products, whether they’re “offline” or “online.”

“I want to see more teachers out there feeling comfortable with representing themselves as industry leaders,” Williams said. “Because we are subject area experts, and we should be the ones who are starting a conversation, not adding to it— and making a lot of money off of it too.”