As we walk towards the new Career Launch Center, Anabel Garza, principal at Reagan Early College High School in Austin, Texas, greets two young men in the hallway. They look up to see who is addressing them then look back down, walking past her without a response.

Garza’s story is well-chronicled, the age-old tale of a principal trying to turn around an impoverished school with failing tests scores. In 2012, a book titled, “Saving the School: The True Story of a Principal, a Teacher, a Coach, a Bunch of Kids and a Year in the Crosshairs of Education Reform,” was written about her efforts. Yet Garza’s career didn’t end in 2012, and six years later, the school is still working towards its happy-ending.

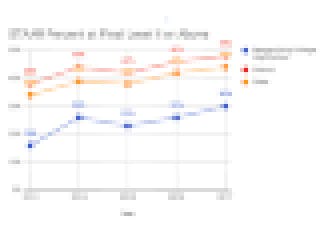

After realizing modest improvements on tests scores over the past few years, going from 16 percent showing grade-level academic achievement on state exams in 2013 to 30 percent in 2017, the teaching staff has deepened their mission. Now their goal is to tackle life after high school—getting their students into college or other viable career pathways. However, with 84 percent of the 1,248 large student body categorized as economically disadvantaged, and with 34 percent of students being English Language Learners, Garza knows the odds are stacked against them.

“How can you take a one-legged man and run him in the Olympics? There are no exceptions because you have more English language learners or more kids of poverty,” says Garza. “It gets tighter and tighter every year. The miracles we pull off here, nobody will recognize them because we are not National Merit Scholars. We took kids who don’t even speak this language, and we get them across the line.”

To get these students “across the line” or to a level of satisfactory academic performance in an under-resourced school, Garza and her assistant principal, Kevin Garcia, have sought out various partnerships with businesses and nonprofits in the community.

These partnerships have helped them start a daycare center in the school, so young women who get pregnant don’t have to drop out. Sharing space with the daycare, two community nonprofits, project Advanced and Breakthrough, support the school by providing volunteers for a modest college and career center. In the center, students preparing for college seek help filling out FAFSA student aid applications and studying for college entrance exams.

Working with Austin Community College, the school has been able to advance their college and career readiness program. Now students take dual credit courses on the community college campus working with the professors. And another nonprofit group known as AVID (Advancement Via Individual Determination) has helped the school create study skills programs to support student retention once they are in college.

But college is not for every student, and after recognizing that some of their students may not attend four-year institutions, the school launched a new endeavor last September. Together with Austin Community College, Austin ISD and Dell, the school began an associate’s degree program in computer science with a cybersecurity pathway.

The subject area was an intentional choice. Last January campus officials decided to teach cohorts of students cybersecurity because the Texas Workforce Commission identified it as an in-demand career pathway. Then, after the school received an innovation grant in February, they reached out to feeder schools to identify 8th-grade students who performed well in logic, critical thinking and showed interest in information technology. This school year 39 students began the program, which they hope to expand to 50 in future cohorts.

Speed Bumps On a New Pathway

As we enter the colorful, open Career Launch Center (a space designed for students in the new program), we see various seating options, virtual reality headsets, whiteboards, television screens and tables of different shapes and sizes.

“In order to prepare our students for success in postsecondary careers in information technology and cybersecurity we had to create an environment that mimicked the workplace,” says Garcia, explaining how the school received an Innovative Academies Models grant to redesign the space.

To design this program, Garcia has looked to other public high schools with similar demographics, such as Pathways in Technology Early College High School (P-TECH) in Brooklyn. P-TECH partnered with IBM back in 2011 to design a six-year high school where students receive associate's degrees in STEM majors and sometimes job offers from IBM by the time they graduate.

But early college programs like the P-TECH model have struggled with completion rates. In an interview with EdSurge last year, P-TECH principal Rashid Davis noted anxieties students experienced when watching their peers in four-year schools graduate while they remained in the six-year program. “They are too close to completing their degree to give up now,” Davis told EdSurge. “Completion is the goal.”

Though Reagan Early College High School is not yet a six-year program (Garcia, however, did note that he is thinking to turn it into one), completion has been a pain point at the campus. According to data from the Texas Education Agency, the graduating class of 2016 started with 326 ninth-graders, but only graduated 243 students or 74.5 percent—lower than the national average of 83 percent, calculated by the National Center For Education Statistics.

However, problems with completion do not primarily stem from dropouts, which were recorded at 2 percent in 2016. Garza explains that the problem with completion at her campus comes from student mobility or the number of students who have to move out of the school during the year. At Reagan a whopping 25.8 percent of students had to move during the 2015-16 school year, much higher than the state average at 16.2 percent.

Garza tells EdSurge that gentrification in her area has caused many students to lose their homes. “We found out our kids come with heavy loads. When something is wrong with your own family, and you come to school, that is all you can think about. It’s the same with kids,” she continues. “They think, ‘my mom said we are going to be evicted tonight and out on the street, so what are we going to do?’”

Survey data from 2013 estimates a 12 percent increase in housing costs around Reagan Early College High School's neighborhood over a four-year period. Last January a report from realtor.com identified Austin, Texas as the 10th-fastest gentrifying city in the nation.

Yet in spite of the rapid gentrification, and the other strains related to poverty and proficiency, Garza is hopeful about her campus’ new efforts to prepare students for life after high school. She says she will continue to add partnerships and programs in hopes that each new thing pushes the needle on achievement forward. The school leader recently opened a family resource center to support students who are being evicted from their homes. Next year, she hopes to partner with the military to expand the cybersecurity program.

“I don’t have secrets. All these people around me believe in kids, and we are going to push them,” says Garza. “They get tired and are overworked, but they are trying to close huge gaps.”