PORTLAND, Ore. — Wayfinding Academy doesn’t look like a college. In fact, it’s easy to walk past its building without even noticing, since the yellow clapboard structure blends seamlessly with its surroundings in one of the few affordable neighborhoods left in this quickly-gentrifying city.

The building once housed a YWCA. These days, walking around inside means experiencing a live-action critique of traditional higher education. Classrooms aren’t numbered, or named after rich donors. Instead they bear designations like Fireside Room, Navigation Hall and Gratitude Vault. Meanwhile, the names of small donors (ranging from $100 to $2,500) adorn small brass plates in all kinds of unusual places—above a toilet-roll holder in a unisex bathroom or over electrical sockets and next to light switches.

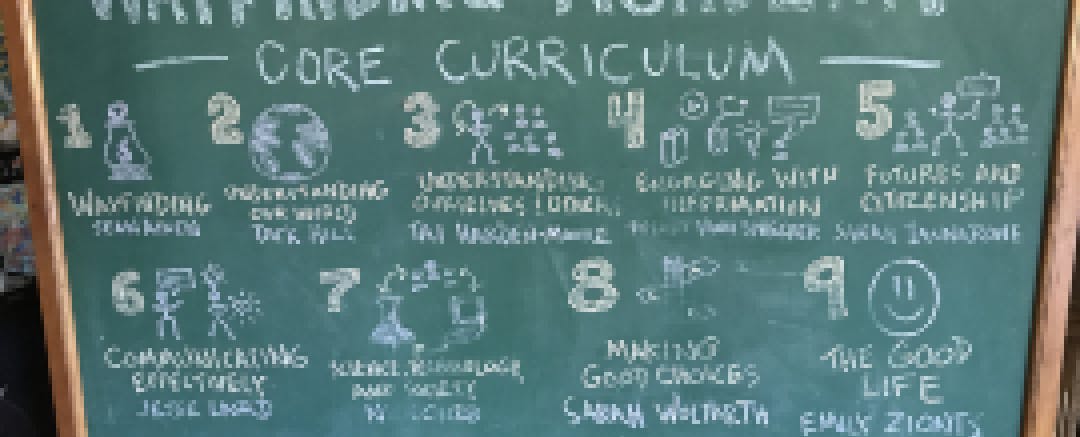

And it’s hard to miss Wayfinding’s unusual curriculum, which is sketched prominently on a chalkboard as you enter its largest common space.

That curriculum is designed to flip the college priority list. Most campuses stress academics, then provide students with activities and guidance to figure out what they want to do with their lives. At Wayfinding Academy, the top priority is self-discovery, with academic content as a background feature. Wayfinding’s leaders say their academics are just as rigorous as any other college—they’ve gained approval from the state of Oregon to grant degrees, and they’ve started applying for accreditation so they might eventually qualify for federal financial aid.

While there are plenty of ways for students to customize their studies here, the two-year college offers only one degree: an associates in Self & Society.

The big idea is to address a pervasive problem in American higher education. Though two-year colleges are enrolling a more diverse mix of students than ever before, about 43 percent end up dropping out before finishing their degree. Most of the students at Wayfinding have tried college before and didn’t fully buy into why they were there, or see how taking required classes would help them. The goal of Wayfinding Academy is to give students greater control and guidance so they’re more driven to reach the finish line.

But the college also attempts a scattering of smaller innovations and unusual practices—so many that it’s easy to imagine a slate of TED talks on the different approaches here. There are no grades, for instance. Everyone on staff, even the president, is paid roughly the same salary (between $30,000 and $35,000) to keep student tuition low, and most everyone has a mix of teaching and administrative roles. And the college raised its initial funding with a crowdfunding campaign on Indiegogo, netting $206,000, which helped buy the building and prove interest in the idea.

Michelle Jones, Wayfinding’s 41-year-old founder and president, might end up giving TED talks on each of those facets someday. After all, she has organized local TEDx events around Portland for several years, which has given her a rich set of connections with local business, government and nonprofit leaders. But she is also a traditional academic, with a PhD and more than 15 years of experience teaching at two and four-year colleges.

Jones’ experimental college is born of her frustration with what she calls “corruption” in the traditional structures of higher education that keeps institutions from actually doing the lofty things they claim to do for students. “My role as a faculty member was more about sorting and grading and checking boxes than it was about helping students find out who they wanted to be,” she argues.

It’s worth noting that the course Jones taught at nearby Concordia University Portland, before quitting to start Wayfinding Academy, was called Principles of Management and Ethical Leadership. Jones has long explored how to make institutions run more effectively. And she says her personal goal is to live a “purpose-based life,” one that isn’t neatly summed up on a resume or business card.

Seven years ago, that passion led her to become a key organizer of an unusual Portland event called the World Domination Summit, a weeklong celebration of “unconventional thinkers.” Summit leaders and participants called her the magician, because she could make big ideas for the event quickly and effortlessly come to life, like finding a way to do a champagne toast for hundreds of people, or handling other logistics intended to delight attendees during the weeklong series of talks and networking mixers.

Jones took the reputation to a new level when she arrived to the conference one year in magician’s robes. And once she had the attention of the conference goers, she used the opportunity to announce the crowdfunding campaign for Wayfinding Academy. She told the audience that she has long been a “real professor,” which means she gets to wear academic regalia every year at commencement. At that point in the talk, she peeled off the magician robes to reveal her academic robes underneath.

“I care very very deeply about the role of higher education in our society, and my own personal calling is to help young people figure out what they want to do with their lives,” she told the crowd. “Our culture of higher education is backwards. We first ask young people to first pick a four-year university to attend, and then to choose a major from some list, and then to figure out what they want to do, and then to go try it. And I feel like we need to flip this frontwards.”

Choking up a bit, Jones announced that she would be leaving her role as the summit’s magician to start her own college to try to address these problems. “I hope that I get to take with me some of the magician skills I’ve learned by serving this community over the past five years, and use it to nudge change in higher education. No tricks, just community, and…” she said with a dramatic pause, turning around and pressing a hidden switch embedded in her robe, causing strings of LED lights sewn into it to illuminate, “a little bit of magic.”

Not everybody thinks this new institution is needed. After all, plenty of traditional community colleges are experimenting with so-called Guided Pathways programs that have similar goals of helping students choose their major and stay on track. Forging a whole new college brings plenty of new challenges, and forces students to take a gamble on an unproven educational entity with no name recognition. And Jones admits that guidance counselors at high schools she’s approached have been reluctant to recommend the unusual college with no accreditation.

Rufus Glasper, president and CEO of the League for Innovation in the Community College, says one test for this and other new two-year colleges is looking at what kinds of jobs the students end up getting when they finish. The price tag is $10,500 per year for the two-year program, and about half of the students have some sort of scholarship to reduce that.

The first students enrolled at the college will in a way be guinea pigs to see if the model will be worth the time and cost. That graduating class is small, just eight students, and a second cohort of 14 students are slated to finish their first year of the program. But Jones is finding out the challenges of putting all those big and small ideas into practice.

Focus on Advising

In the spirit of the name, Wayfinding Academy students spend an unusual amount of their time with their assigned Guide, a college official who plays a role that is part academic advisor, part life coach, part career counselor. While traditional colleges may require students to meet with academic advisors once or twice a year, students at Wayfinding Academy meet with their Guide every week.

Those weekly meetings typically last 45 minutes, structured around four key themes: professional, academic, personal and portfolio. Before each meeting, students fill out a form on Google Docs noting key issues they’d like to discuss, and each meeting ends with a “do-out,” homework for what they want to accomplish before the next week’s meeting.

“In the vast majority of meetings we run out of time,” says Poe Stewart, one of the Guides, who is also the Director of Technology for the college. “I get to know the students really well. The program is really designed to have that depth built in.”

Before coming to Wayfinding, Stewart worked as an instructor at Outward Bound, as well as at a variety of software companies. Despite his dual role as Guide and administrator, the job is only part time, so he can help with childcare for his two young daughters.

Guides also hold group advising meetings each week. Some weeks, that means he meets with all five of the students he advises at once. Other weeks, the entire cohort of students and their Guides meet together. Sometimes those meetings function like classes on life skills—a recent session focused on teaching students how to become better self-directed learners. “One of the main skills students come away with is the confidence and skills to be able to teach themselves once they leave,” says Stewart.

In another group advising meeting, the time was spent celebrating the end of the semester. Students were asked to bring a beverage and stand in a circle, and most grabbed a LaCroix from the kitchen and gathered in Navigation Hall.

“We’re going to go around the circle, and we’re going to name an accomplishment at Wayfinding, and then we’re all going to cheers,” said Tiffany Vann Sprecher, another Guide at the college who led the session.

“I got better at talking in class this term,” said one of the students. “Yeah you did,” replied the Guide, who is also one of the professors. And the students brought their cans of sparkling water together in celebration. Another student offered that she co-hosted two art shows this semester, and one said she signed up for a new lab class. Cheers! They continued twice around the circle sharing and reflecting on what they had done.

Class sessions at Wayfinding Academy look pretty traditional, at least at first glance. During a recent class called Engaging With Information, students broke into small groups to discuss articles they read for homework, then talked as a larger group about key points.

The professor, Vann Sprecher (the Guide who led the cheers earlier) previously taught medieval history at Kingsborough Community College in Manhattan until, as she says, “I had a kid and couldn’t live in New York anymore.” Teaching at what she describes as “a new two-year college that really emphasizes a customizable education” has meant some adjustments. For one thing, students quickly asked her not to lecture. “Most of the students have been in the model already and they don’t love it,” she says. “They don’t like this old model of the sage on the stage.”

She says that she and the students have developed a variety of strategies to keep discussions productive and keep everyone involved. For instance, the do what they call “stacking,” meaning that if multiple people raise their hands, everyone who did gets to to speak in the order they put their hand up. They’ve also developed a class motto to “be ok with non-sequiturs,” meaning that students are encouraged to voice connections they notice between class material, and say, popular culture or something else they see as related.

Perhaps the biggest change for Vann Sprecher is what she teaches. The curriculum at Wayfinding Academy is essentially divided into nine macro-courses organized around broad themes rather than narrow academic disciplines. Among the course titles are “Understanding Our World,” “Understanding Ourselves & Others,” and “Science, Technology & Society.” For more focused explorations, the college offers smaller lab units, such as one in physics, or helps the students to set up independent study projects.

Vann Sprecher says she still “dabbles” in research in her field. For instance, she’s editing a book on Medieval marginal figures, but that’s optional. “I don’t have the pressure to publish—I can do all of it on my own terms,” she says.

‘Hard to Explain’

Meg Lamberger, a 21-year-old student at the college who grew up in Portland, says it is hard to explain Wayfinding Academy to outsiders. In fact she admits she didn’t fully understand what she was getting into when she started. “Wayfinding is an experience,” she says. “It’s not so much a school. You’re joining this community of people who have the same goal and really want to work together.”

Lamberger first heard about the college on social media, when someone shared the link to its crowdfunding campaign on Indiegogo. She put a calendar reminder on her smartphone to ping her in a year, when the college was then projected to open.

“I was really drawn to how individualized the program could be,” she says. “I felt sort of directionless. I know I’m really smart, but I don’t know what to do with that. I had a lot of friends who went off to college and partied and took a lot of yoga classes. But I need to make sure that my time in college is time well spent because I need it to be money well spent.”

In the meantime, she took a few classes at Portland Community College and tried to figure things out on her own. When that calendar reminder pinged on her phone, she had pretty much forgotten about Wayfinding. She started an application to be part of the college’s inaugural class, which involved a conversation with someone from Wayfinding. But she ended up deciding she wasn’t emotionally ready to make the most of the experience and didn’t complete the process. A year later, Jones, the college’s founder, reached out by email to see if anything had changed. Lamberger ended up applying and joining the second cohort.

Like several other students I talked to, she mentioned that she has had to work at “unlearning” education as she knew it, mainly around grades. “I did well in traditional school, but I was very unhappy all throughout high school,” she says. In retrospect, most of what she did was to please a teacher. Since Wayfinding has no grades, students end up as their own toughest judge of whether they are making progress.

That might sound even easier than an easy A in the traditional system. But Lamberger and other students argue that it’s more rigorous. “Pleasing myself is way harder than pleasing any teacher I’ve ever had,” she says. “I miss grades,” she says with a laugh. “I miss grades so much.”

But without the traditional grading scheme, Lamberger admits she can get away with slacking off here and there. “I’ve had a couple of projects where I’ve thought, ‘This is good enough, and I have to prioritize something else,’” she says. The opposite is true, too, and she’s been able to find projects that she’s especially curious or passionate about. She points to other assignments she’s done that she’s particularly proud of and invested in, including one where she analyzed an unusual private museum run out of a collector’s home. She called up the man who ran it and arranged a private tour and interview as part of her research—a move outside of the classroom that is encouraged at Wayfinding.

That’s not to say Lamberger doesn’t raise questions or suggestions on a regular basis—she does. Sometimes she’s the first one to ask the question (say, about the college’s policy on something) and administrators ask for her patience as they come up with an answer. But she says that everything with Jones, the president, feels intentional. “Michelle talks about how there’s always a Why,” the student says.

Making Time for Life’s Passion

Plenty of people love watching TED talks, and Michelle Jones is one of them. Many years ago she attended a TED event in India for a vacation. And she is far more likely than most to going out and acting on an idea presented in those slick 18-minute presentations.

So I wasn’t surprised to learn that Jones lives in a “tiny house.” “It’s 8 ft wide and 14 feet long,” she says, and it’s parked in an acquaintance’s backyard near Wayfinding Academy. “I wanted to simplify my life so I could spend as much of my time and effort doing my life’s work as possible. One way is to live in a small space and have a low cost of living.”

She moved into the house before she started her college, but she says the decision is what made it possible to live for two years without a salary as she got Wayfinding off the ground.

Jones infuses that spirit into the college in ways that some may find gimmicky or over-the-top.

Consider how the college handles notifying students they’ve been accepted. Rather than sending a letter or email, Jones (or another college official or student) shows up at the accepted student’s house in person to tell them the news. They present the student with a wooden box embossed with the college’s lantern logo, and inside is a cap and gown (and a few other things).

“We call it commencement day because they’re starting something new,” explains Tiana Tozer, the college’s director of student recruitment. “Commencement for us is the beginning because we’re trying to turn higher education around frontwards.”

Officials admit that recruitment has been slow-going. Though they had talked about having up to 24 students in their second cohort, only 14 signed on. In some cases, Tozer finds herself talking a student out of the college, such as when an applicant expressed a passion to be a forensic psychologist, a job for which there’s a clear educational path at traditional colleges. “Wayfinding Academy is not for everyone,” she says.

“We put the word out through gap programs, uncollege and homeschooling,” says Tozer. “Those are students who are already nontraditional students and so Wayfinding often has more appeal to them.”

The college also hoped to attract a more diverse group of students, and it is actively working on the issue. When she’s not working at Wayfinding Academy, Tozer is an advocate for people with disabilities—she’s given many high-profile talks about her own experience as a paralympic wheelchair athlete, including the 2013 commencement address at the University of Oregon.

But as Jones explains in a recent essay she posted on LinkedIn, all of Wayfindings initial class were predominantly white. “That was not our intention and not all of the students who applied nor all the students invited were white, but all the students who ended up enrolling were,” she wrote. “Even though we have backgrounds in equity, inclusion, and social justice, you couldn’t necessarily see that or tell that just from looking at us.”

The second cohort is far more diverse. “In our second cohort of students, 29 percent are students of color and 23 percent are students who identify as non-gender, non-binary or transgender,” Jones says.

Jones says the college is on a path to sustainability, and that over time she plans to raise salaries for all employees modestly (though she still plans to pay everyone roughly the same amount). She says so far recruitment hasn’t been a problem, though one person she wanted to hire said he couldn’t afford relocating to Portland for a $35,000 annual salary.

Officials from a handful of colleges have visited the campus to learn from what it’s doing and possibly bring back ideas to their own campuses. They have questions like “If you have no tests and no grades, how do you do this?” says Jones.

Bernard Bull, vice provost for curriculum and academic innovation at Concordia University Wisconsin, says what feels most important to him about Wayfinding was how it got started.

“To my knowledge that’s the first time we’ve ever had a university that’s launched by crowdfunding,” he says. “It’s an example of a startup higher-ed organization, and we don’t get to see too many of those.” He praised how iterative its development seems and the role students appear to be playing in how the college is evolving.

Bull first heard of the college when he saw the Indiegogo campaign, and he says he put in a little of his own money to support it. “How many times do you get to invest in the launch of a new higher-ed institution?” he asks. In his home office he has the lantern they sent him as a thank-you gift.

A big question still remains for students and crowdfund-backers: Are the students finding their way?

Austin Louis, one of the students graduating later this year, has decided to look for jobs within alternative education, and is even talking to Wayfinding about sticking around in a professional role. He dropped out of Babson College in Massachusetts his sophomore year because he “didn’t feel like he was learning anything.”

“A lot of the reasons of why I have done things in the past has been trying to please my parents,” he says. “I ended up digging up all this trauma and grief that was in my family,” he adds. “Sometimes you can get really vulnerable—it’s about who we are and why we do the things we do. What gets me most frustrated is seeing people that I care about, friends back home, that feel trapped in this dull, uninspired life.”

Lamberger, for her part, says she still doesn’t know what she wants to do with her life, “to some extent,” but says that she is glad she jumped in and feels supported to figure it out. She expects to transfer to a four-year college after Wayfinding, perhaps another nontraditional college.

And it’s still early—she just started at the college this fall, and she has more to learn, and unlearn, on her educational journey.