Here’s a popular movie plot: Great teacher goes into a troubled neighborhood and turns around a low-performing school. Educators love the messages from these films, and even children are inspired. Unfortunately, many school districts never find the Coach Carters or Erin Gruwells who bring such happy endings. In fact, in a broken district such as Detroit’s, schools in hard-bitten neighborhoods sometimes go from “turnarounds” to closure.

Fisher Magnet Upper Academy is a middle school located within one of the toughest neighborhoods in the city, stricken with poverty and crime. In 2013, local news reports named the area the third most violent zip code in America. In 2016, Fisher was named one of the 38 campuses at risk of closure after the Michigan legislature passed a bill saying any school ranked at the bottom 5 percent of state campuses for three years in a row would be subject to consequences.

Despite a relatively new building, constructed in 2003 as part of a former superintendent’s turnaround project, Fisher has suffered from consistent low performance—falling far below state standards on exams and adjusted growth targets designed specifically for the school. During the 2015-16 school year, only 0.7 percent (3 out of 451) of students met state standards in math, and only 4.5 percent met English Language Arts standards.

Carl Brownlee, a former United States Marine officer, is a middle school social studies teacher at Fisher Magnet Upper Academy. He has been teaching at Fisher for over 10 years. He believes changes in academic performance can happen in a struggling school like Fisher but says he has only seen it happen in the movies.

“The only person I have seen that had the ability change this type of climate and culture was Joe Clark, or Morgan Freeman in that movie, ‘Lean On Me,’” says Brownlee. That doesn’t mean he thinks improvements are implausible, though. He says: “I think there were some good ideas that movie that you could translate into schools.”

Brownlee believes that he is a good teacher, in spite of what test scores may reflect. And he feels as though his students have been slighted by ineffective teachers in the past. So he plans to stay at Fisher, where he hopes to bring advanced teaching skills to students that other educators may ignore.

“My children are being cheated because they are not given the same experiences as their counterparts in other schools, and that’s not fair,” says Brownlee. “That’s one of the reasons I stay where I am at.”

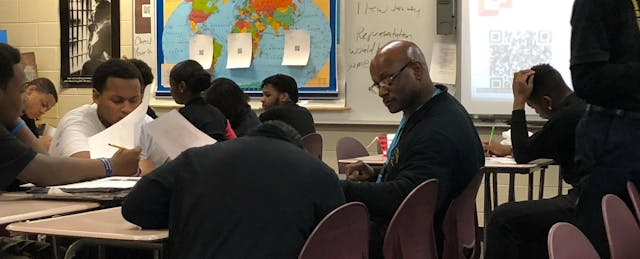

As students trickle in Brownlee’s classroom on a Friday morning, he stands by the door to greet each of them. He instructs them to grab their work folders and get into groups. The 6th, 7th and 8th graders entering Brownlee’s class in their uniforms are respectful, quiet and—though naturally distracted from time to time with whispers and giggles—appear to be on task. They ask questions and support one another as they move around in groups through learning stations Brownlee has set up in class.

Technology has a role to play in Brownlee’s effort as well. Using the free version of tools such as Edmodo, Kahoot, and Google Forms, Docs and sometimes Slides, Brownlee varies his lessons on topics such as Chinese history and the Missouri Compromise. He opens up classes with hip-hop education from Flocabulary, then goes into worksheets, videos, group assignments, and desktop assignments—incorporating cell phone apps and music in the activities. He constantly walks around the room, refocusing off-task students and offering feedback on their work. His classroom does not fit the “before” image in most romanticized school turnaround stories.

“The skill sets that I have, I like to use them with these young people instead of going to another school where you might get the test scores that people are asking for,” Brownlee continues, noting that he is not looking to teach the “ideal student” in an exemplary school. “My kids don’t come from that, so I try to hang in there and do my best. They need it. They deserve it.”'

By “doing his best” Brownlee means constantly learning, often looking for resources outside of the district for support. He is also trying to incorporate more personalization into his classroom, noting that the State Department of Education has embraced the implementation of such instructional models.

Since Fisher does not have enough Chromebooks for every student, teachers share a cart of laptops that travel from class to class. Teachers also combine technical and non-technical ways of personalizing instruction. For Brownlee, part of personalization means gauging the social and emotional well-being of students each morning, so he knows how to approach them throughout the lesson.

“Are they ready for school work? You might have [a student] come in who just had a loved one die the night before. We have had that on many occasions. They still come to school,” explains Brownlee. “You can’t just go into teaching when they come into the classroom if you don’t know where they are at.”

To meet students where they are, Brownlee has a couple of go-to tools. He uses apps such as Quizlet to encourage students to learn independently. In addition, he uses Edpuzzle when students are having a hard time with particular topics in class. The app allows them to rewatch annotated video lessons.

“I have done it with several of our resource students,” Brownlee explains, noting how one struggling 7th-grader has been showing improvement since using apps like Edmodo and Edpuzzle. “He comes to class every day, and you can see that he is trying. He wants to understand what is going on. He likes to look at the videos, and his effort is starting to show in his work. You get a little joy when you see them getting it.”

Brownlee also has digital portfolios that he uses to track student mastery and growth, something all teachers in his school incorporate. Yet, he notes that this method has yielded mixed results, particularly since many teachers serve a large number of students--and struggle to keep records up to date.

Brownlee works with 198 students daily and admits its difficult for him and other teachers to add student work to the portfolios consistently. “It’s just very difficult when you have so many students to try to personalize for each one,” he says. “You can tailor for each student, but only to a certain extent.”

Despite the difficulties, Brownlee has not given up trying to tailor instruction for his students. He makes time to celebrate the small gains he sees students making, like the lessons he teaches that students remember long after they graduate. But he admits that there are days that he gets tired, particularly noting the difficulties keeping up with changes in the district.

His district has flipped between state and local control over the years and has had a number of different superintendents and principals; most of them bring new initiatives with them. This school year Brownlee has a new superintendent and a new school principal, but real-world challenges facing students in and out of his school continues. He is cautiously hopeful that things can in improve, but the familiarity of changes that don’t yield academic results is haunting— causing him to work overtime with his happy-ending out of sight.

“No matter what you do you are still going to be accountable for the test score. It does not matter if the students just came from another school or district. It does not matter if they came to you four grades behind, if that child’s family is impoverished, or if the child has any type of learning disability that may be undiagnosed,” says Brownlee. “It is more like a professional football team. If the team does not win, it is the coach’s fault, and the coach is fired.”