Alongside thick textbooks and study guides, biomedical students at Drexel University may find themselves playing video games in preparation for exams in the near future.

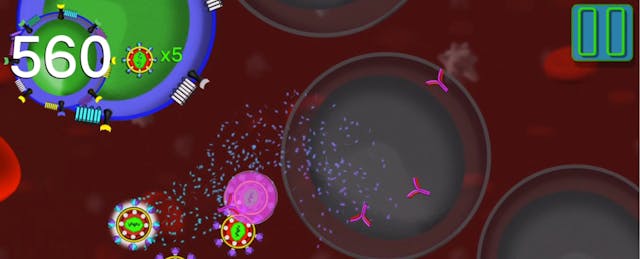

But instead of Super Mario or Zelda, they’ll be playing a game called CD4 Hunter, which launched last June and focuses on teaching students the first step in the HIV replication cycle. In the game, players roleplay as the virus and are charged with moving throughout the bloodstream to identify receptors, get past immune defenses, and target and infect cells.

Sandra Urdaneta-Hartmann, an assistant professor in Drexel’s Department of Microbiology & Immunology, never really considered herself a gamer growing up, but has been driving the development of CD4 Hunter and its introduction into biomedical school courses.

“There was a strong interest from my department head—and myself—to explore using mobile games in our programs,” she says. That’s different than simulations, which are more common in biomedical education and training but lack game-based elements.

Gaming in education, and in particular around biomedical training, has been widely researched—but comes up with mixed results. While one study found scores on a video game correlated with students’ surgical skills. Other reports, however, have shown negligible results from educational games in medicine.

Among the differing opinions and research, what Urdaneta-Hartmann struggled to find were any science education-based games that aligned with her department’s curriculum. So, she decided to build one herself.

Without much of a clue as to how to design or program a game, Urdaneta-Hartmann won a $10,000 grant from Drexel to develop her own skills in educational gaming and create a tool for students in the program.

With the funds Urdaneta-Hartmann traveled to Norway for an educational gaming conference. There, she recruited another microbiologist, Carla Brown, and together the two came up with a plan to build a video game based on the life and replication cycle of HIV—one of Drexel’s areas of research expertise.

“That was the most logical path to go,” Urdaneta-Hartmann says. “Let's start with something we know well enough, so that's not another hurdle we need to jump.”

Even with an idea, the duo was still missing a crucial skill set in the game development: programming. So the team turned to the Drexel’s cooperative-education program, which requires undergraduate students participate in a professional learning experience before graduating. Through the program, Brown and Urdaneta-Hartmann hired Vincent Mills, a senior at Drexel University majoring in Game Art and Production.

With Brown as the developer and designer, Mills in charge of coding, and Urdaneta-Hartmann providing subject matter expertise, the team had a working version of the game ready to show in about nine months.

So far, Urdaneta-Hartmann claims the CD4 Hunter app has nearly 2,900 downloads on the iTunes store today.

“We don't know how the word of mouth is going around,” she says, “but it's cool to see these stats, and it's encouraging us.”

But the assistant professor admits their game is a trimmed-down version of what she initially envisioned.

For example, CD4 Hunter has only one stage that can be played in about 30 minutes and is meant to supplement instruction—originally the team had envisioned seven levels for each stage of the HIV reproduction cycle.

Now, Urdaneta-Hartmann is the in the process of designing curriculum for faculty and instructors to test out the game next fall with students.

Ways of introducing the game to students include discussing the content in class and assigning the game as homework after, or using a flipped model, by assigning the game and asking students to come prepared with questions and discussions topics.

In the meantime, the team has also tested their game with undergraduate students in the Microbiology and Immunology Department at Drexel, as well as at the university’s Entrepreneurial Game Studio.

“We plan on tweaking according to [student] recommendations and then test the game to see if it improves learning over just instruction alone,” says Mary Ann Comunale, a research instructor in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology, who was brought on to evaluate and gather student feedback.

A few initial—albeit informal—findings have already been illuminating. For starters, Comunale says the competitive nature of the game has suited students in the department.

“It was funny, when I was looking at students as they were playing, all I had to say was ‘my last group got a high score of X,’ and all the sudden they were going at it,” Comunale says laughing. “I don't know if it's just med students, but they can be a competitive bunch I'll tell you.”

Comunale and Urdaneta-Hartmann hope to eventually finish out each of the seven levels for the CD4 Hunter. But that will have to wait until after their next project, a video game on malaria. The idea is to eventually have a whole suite of mobile games that students studying microbiology can use to study.

“We are working on malaria, a parasite, and we want to later create one about bacteria and fungi,” says Urdaneta-Hartmann.

For other instructors who want to develop their own educational games for students, the professor says to start by asking what the learning goal is and how competitive gaming can support that.

Mills, the student programmer, has his own advice: make sure it’s fun.

“There is always some amount of learning that a player does no matter what game it is,” he says. “But when someone sits down and actually sees and interacts with the environment in a way that is scientifically accurate and fun, it becomes easier to memorize or understand what happens in the real world.”