When educators first consider redesigning learning spaces, they might immediately conjure up mental images of free-flowing Starbucks lounges or something out of the Cult of Pedagogy blog’s Classroom Eye Candy series. Yet the impulse to tackle aesthetics first is often premature, according to Rebecca Hare, who teaches art and design in St. Louis and has served as a design consultant for various schools.

“So often I work with schools across the country going through this process, and everybody comes to me with the catalog and says, ‘We love these tables, what do you think?’” says Hare, who, together with tech director Bill Selak, will present a strand of sessions around designing thoughtful spaces for learning at the upcoming CUE Bold conference, May 5-6 in Laguna Beach, Calif. “Nobody comes to me and says, ‘We have this incredible vision for learning, what do you think?’ So you really have to walk people back to the higher vision.”

Before coming to education, Hare spent a decade in Italy designing commercial and retail spaces, where she learned to tailor her work to the end user. She returned to pursue a master’s in education and has since helped schools locally and in Miami rethink their environments, often under tight budgets. Selak, who works at the private pre-K through 8 Hillbrook School in the Bay Area, has worked for years on a similar goal, playing a major role in a continuous series of redesigns and remodels aimed at centering learning on student needs, as opposed to asking them to adapt to the space provided.

For Hillbrook, the “Big Why”—the phrase Hare and Selak assign to an overarching vision—has become, by turns, about student autonomy, making and creation, as well as a seamless fusion of technology and environment in an era where ubiquitous WiFi and mobile devices have untethered kids from the traditional concept of a classroom.

“I’m in a school with 1:1 iPads,” Selak explains. “If we’re not giving students choice around space, and not making the space look different, then we’re doing something wrong. Good lesson design, good technology integration and thoughtfully thinking about space—if you’re doing them well, they can’t live without each other.”

The Design Thinking Approach

The trick to creating an effective learning space is to build in a certain amount of agility when designing it, Hare says. Teachers can start simply, with the overall goals they have for their classrooms, the types of projects they want to do and the mindset they want to instill in students. “Really, you do a lot of work in the beginning and then choosing the furniture is quite simple,” she explains.

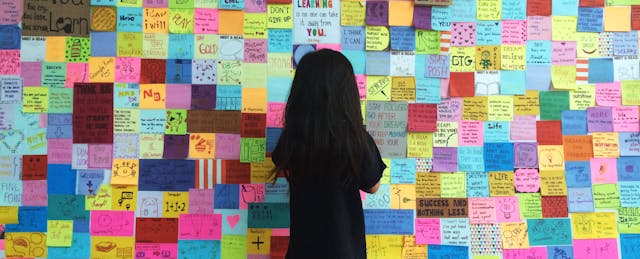

As for building in agility upfront, that comes in handy later, after students have gotten a chance to experience the space and figure out which elements are working and which need tweaking. When she goes into schools as a consultant, she hopes for one thing: “An educator who's going to feel comfortable enough to give power to the kids to say, ‘Hey, is this working? Are you able to learn this way? How can we design this better?’ Because then the kids have control and their voices are heard and the space functions completely differently.”

Rarely, Hare says, are teachers—let alone students—consulted about classroom technology and furniture choices. Instead, high-level administrators and facilities managers make top-down decisions (“and they never set foot in the classroom, except to take measurements,” she adds wryly).

Selak’s school, however, has opted for a different path. During Hillbrook’s perennial transformation, staff committees work through the process of reimagining classroom spaces using methods based on design thinking, a user-centered approach to identifying problems and solving them using empathy, listening skills and quickly spinning up prototypes to try and learn from. Thus, instead of treating the redesign as one big project, the school broke it down into parts that could be completed with more alacrity.

Peeling Back the Onion

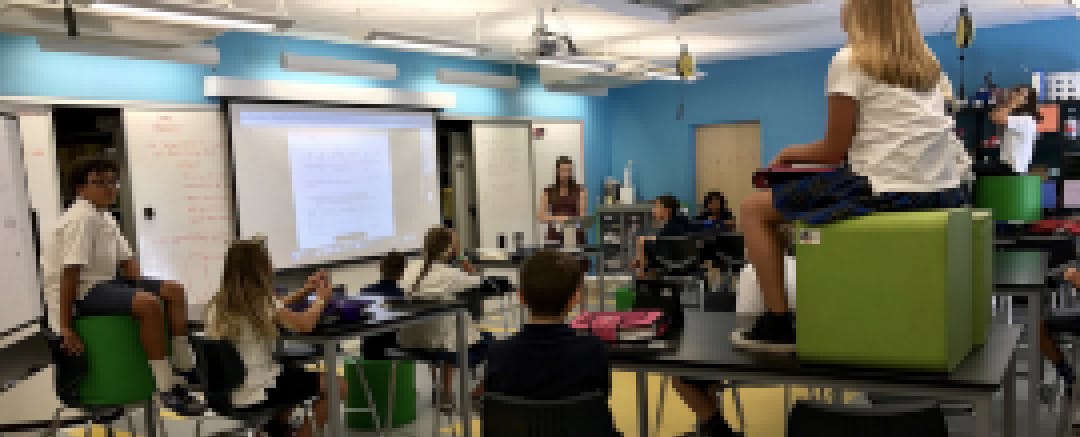

Looking back, Selak likens the process to slowly peeling back layers of an onion. The first step for the school was an early foray into open design called the iLab, where flexible furniture mingled with makerspace elements and power tools. Then a group of 12 teachers worked with a research designer to remodel their classrooms based on the concept of putting student needs at the center.

The following year every classroom went through the redesign process, ending up with a collection of classrooms that share some similar attributes, like tables and seating, but spread differently. Finally, the school is working on building a new art and science space called the Hub, which incorporates best practices from previous redesigns: Tables and chairs are all fitted with casters for easy movement, and special ceiling mounts let students hang pulleys, artwork and even extension cords for power tools, enabling multiple configurations in a single day.

Along with the physical design, the school is also rethinking the scheduling system it’s had in place for the past decade to give students more flexibility in the “when” and “how” of their learning—in addition to the “where.” Again, school leaders teamed with teachers to utilize elements of design thinking to figure out their needs. Selak sat on the scheduling committee over a 2-year period, helping conduct interviews and shadowing students throughout their days.

“When it’s the right tool, design thinking can be so powerful,” he says. “I think the power of design thinking is about the user and taking an iterative approach.”

Getting kids to weigh in has an even bigger benefit, Hare adds, in that it serves as a profound learning experience, teaching them about problem solving and introspective thinking to help them determine what they need from the walls, furniture and technology around them. Ultimately, math classrooms will evolve differently than English classrooms, and every space will look just a little different based on who’s occupying it at the time.

But first things first, she reminds educators: Put away those catalogues.

“When people say, ‘Oh I love the tables in that room,’ I say, ‘That’s awesome, but think about what’s going to happen in your space that's going to be amazing,’” Hare says. “It’s about supporting your kids as learners and creators.”