Last fall I started my first day on the job as an embedded faculty member with a corporation—as a scholar-in-residence at Steelcase Education. But don’t be too impressed by the title; according to the employee system, I was just an intern.

Actually intern is probably the best lens through which to look at what I’ve been doing at Steelcase for the last eight months. I was nobody special: Just a guy, at the bottom of the org chart, working with and around a lot of people smarter and more talented than I am in any number of ways, and tasked with making their work and the collective work of the organization better. It’s kept me a little bit humbler than I would have been otherwise.

I’ve always felt like I was conducting two sabbaticals at the same time. The public sabbatical, the one that I proposed to my university and to Steelcase, centers around being on-site at Steelcase headquarters in Grand Rapids, conducting research on active learning and active learning classrooms and communicating that research to Steelcase audiences and customers. In this public sabbatical, I have learned a ton of new things, mostly about education research methods and what we know from those methods about how learning spaces interact with pedagogy and technology to affect student learning.

But I’m not going to report back on those things for now. Instead, I want to write about my secret sabbatical.

The secret sabbatical (so-called because I didn’t really disclose it to Steelcase, also because I want it to sound cooler than it really is) was about using my position as an embedded academic in a corporation to gather all the intel that I can about how private companies work and to see if there’s anything that’s particularly good that could be adapted and brought back into higher education, to make higher education better.

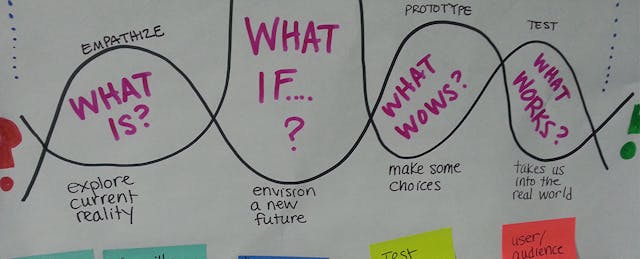

So for the last eight months, I’ve asked a lot of questions of the managers and business types that are around me. I’ve taken part in marathon business strategy planning sessions. I’ve done design sprints with people high up the org chart. I’ve read books like The Innovator’s Dilemma and others that you’d not typically find in the math section of the bookstore. I’ve tried to train myself in the lingo and include terms like “design sprint,” “customer,” “ROI” and so on in my vocabulary. I’ve kept my eyes open, taken a notebook full of notes, and spent time every day processing what I was seeing and speculating about how the best things I saw might function in higher education. Occasionally I even wrote a blog post about it. While I was an embedded academic with the company, I played amateur anthropologist to learn all I could about corporate practices.

Some of the specific questions I was thinking about while doing this have been:

- What do creativity and innovation look like on a day-to-day basis inside a large organization whose existence depends on staying creative and innovative?

- How do leaders operate within such an organization, where there are a lot of smart people and in which innovation and creativity are of the highest importance?

- What practices of really effective companies, in which creativity and innovation are important, seem to have the biggest impact?

- Is there any chance that higher education can appropriate and modify any of those high-impact practices, that would make higher education better at serving student and helping them succeed?

Let me be clear that this is not about “running higher education like a business.” I’ve made it clear before that I think this is a non-starter, because the basic assumptions and models for businesses are different than those for universities. But this doesn’t mean that we can’t learn something useful from our friends in the corporate world.

And let me say: If you’re an academic and the phrase “friends in the corporate world” is offensive, maybe this is a place to start. There are absolutely some corporations that seem to care nothing for people, that embrace unethical practices as normative and focus only on profit. But there are also plenty of colleges and universities that are the same. And, as I have learned, there are also corporations who, while still focusing on being profitable, manage to have their hearts in the right place, care about their workers and customers, and do really amazing things. The first order of business is to think more critically about businesses.

I’ve been thinking for the last couple of weeks about the big takeaways from my sabbatical on this issue. It’s been hard, because I’ve learned and experienced so much that it’s nearly impossible to distill it all down into a short list, and any short list I could generate will oversimplify things. But insofar as I can manage it, as a preview of what’s to come, here’s a list of what I think were the biggest lessons I learned:

- Business and higher education have more in common than we academics think.

- Higher education can, and should, study and adapt the practices of highly effective businesses.

- The most important characteristic of great companies, that higher education lacks the most, is agility.

- Innovation is hard work, needs to be scalable, and needs to be everybody’s job.

- Workplace culture trumps everything.

- In a great company, everybody assumes responsibility for everything.

- There is great power in a diverse team working with a single purpose.

- College faculty are smart creatives.

- The future of work is a whole lot of both-ands, not either-ors.

- Higher education is at a turning point, and it can either adapt and thrive, or stay put and be irrelevant.

When I was first hatching this scholar-in-residence idea almost 2.5 years ago, I knew I wanted to do something radically different—a moon shot that I’d never be able to do while in my regular professor duties or even in a single semester of a sabbatical, and something that would set my professional course for the next 20 to 30 years. I just want to say that it’s been all that and more, and I’ll miss the work I’m doing and the people I’ve worked with when my time’s up in a few more weeks.

Agility and Adaptability

Here I’d like to dig in a bit more about how higher education can, and should, study and adapt the practices of highly effective businesses. And I’d like to argue that the most important characteristic of great companies, that higher education lacks the most, is agility.Higher education is in a state of flux unlike anything I’ve seen in 20 years of being a professor, and perhaps unlike anything for many years prior to that.

Higher education is struggling externally, with funding running out and public support dwindling. It has tremendous PR problems that are not helped by the actions of certain professors. The world around higher education is changing rapidly, and colleges and universities are struggling to stay relevant while making their offerings affordable.

Internally, higher education is beset by cultural and organizational issues that are familiar to anyone who’s worked in higher ed: siloed departments that don’t talk to each other, political fiefdoms that arise over squabbles for resources, faculty who engage in unethical behavior and cutthroat competition, a refocusing away from students and teaching and on to winning research grant dollars—to name just a few.

Not all universities are like this, and not all struggle with the same things. But the internal politics of higher education are real, and whereas in the past the prevailing landscape around higher education could support a certain amount of organizational dysfunction and still produce a world-class education, the world today is different, and those dysfunctions are now revealed for what they are. And if we in higher education don’t change this, we can’t expect higher education to continue on the way that it has for so many centuries past.

It’s a different world, and we have to adapt to it, and learn to live with it.

And to do that, we have to eat our own dog food—we have to learn things. How ironic would it be, if an institution built on learning and discovery finally collapsed because it couldn’t bring itself to look over its own walls and learn from others? We need all the help we can get, and this means getting over whatever squeamishness we may have about the private sector and industry and beginning to look at what companies do, to learn their language and adapt and adopt anything that looks like it could be useful.

One such practice I saw at Steelcase was remote work. When I first started at Steelcase, I wasn’t sure how the whole “showing up to work” thing was supposed to work. When did they want me on the premises? Did I have to clock in, like when I worked part-time jobs in college? Am I in trouble if I come in late? What if one of my kids gets sick—do I take a vacation day, or something? This was all new to me. It turns out I didn’t need to worry about it, because the general philosophy was: We need you to get your work done, but it doesn’t so much matter where you get your work done. It wasn’t uncommon during the week for as much as 1/3 of the education team to be gone—working, but not on the premises. Given that Steelcase is a global corporation, it couldn’t be any other way. And that level of remote work had zero effect on our productivity, or the sense of camaraderie you get from working together.

Universities, on the other hand, don’t seem to like remote work. I recently spoke with a faculty member whose college required he hold ten office hours per week—and they had to be in his physical office. I had a similar rule at a previous institution, and it was not acceptable to hold some (a reasonable, sane amount—like 5 hours a week) in the office and the rest online.

There was a default—a bias—toward physicality. As far as I can tell there are no data involved in making up rules like this. Certainly we need to be physically present for a lot of our work. But why can’t we also work remotely when it makes sense? Wouldn’t a generous remote work policy help out faculty such as parents with young kids who are struggling to find and pay for child care? Or students, for that matter, who have busy schedules too and who will struggle to have the time for physical co-location with a professor no matter how many office hours we hold?

Another interesting practice I saw was that of having organizations within the organization designed to innovate. In The Innovator’s Dilemma, the “dilemma” itself is that of a successful company being trapped in the very habits that caused it to be successful in the first place, only to have smaller companies come along, introduce a disruptive technology that isn’t high-quality at first, but which eventually finds a niche, moves up-market, and unseats the incumbent company which is not prepared to deal with the disruption.

The solution to this dilemma was for incumbents to create small, semi-autonomous companies within the larger companies whose mission was to act as a sort of skunkworks, trying new technologies and acting as an in-house compartmentalized startup. If the new products failed, then the parent company wasn’t harmed as much as if it had itself invested in it; the skunkworks could be closed down without much lasting effect. But if they succeeded, then the successes could be carried over to the parent company, which could then literally own the disruption and reap the rewards.

At Steelcase there are two such companies-within-a-company: turnstone and Coalesse. These two organizations focus, respectively, on architectural products for startups and products promoting collaborative work. Their facilities are located in parts of the Steelcase campus that are a little out of the way, and it feels like a different organization when you walk in. turnstone in particular has done exactly what Innovator’s Dilemma said such an organization would do. For example, the Buoy chair was a product that was introduced and (if I have the story right) took a while to catch on; Steelcase didn’t make anything else like it. But when it finally caught, everybody wanted one, and now it’s a standard part of the package when many schools order active learning space furniture from the main company. Likewise, I’ve seen prototypes lying around the turnstone area that clearly never made it out of the alpha stage and will probably never see the light of day, and it’s no big deal that they won’t because there are enough successful ideas from turnstone that it’s a net win for the company.

It’s rare to see something like this in higher education—institutions within a university, whose mission is to try to enact off-the-wall innovative educational “products,” and who live within the university but essentially function as their own separate organization. Such a sub-university would be tasked with innovating, and if an idea took off, the university could broaden its adoption, otherwise the idea ends up like the failed turnstone furniture. Looking around at the various “disruptive” forces in higher education—digital badging, MOOCs, competency-based education, online education, and so on—what if universities stopped fretting about or dismissing these, and instead developed their own skunkworks to get out in front of those ideas and do them right and avoid being disrupted?

That gets me to the power and necessity of agility.

Agility means the ability to move quickly and easily. Agility requires awareness of one’s surroundings, knowledge about one’s context and the ability to learn and respond quickly to changing situations. It has the same essential meaning whether we are talking about a soccer player making a break toward goal through a stout defense, or whether we are talking about an organization trying to conduct its business in a rapidly-changing environment.

The best companies seem to be defined by their agility. Steelcase certainly had agility in great quantities. Sean Corcorran, who for most of the time I was on sabbatical was the general manager of Steelcase Education, said something in a meeting that really stuck with me: The only real competitive advantage we have over anybody else is that we learn faster than anybody else.

It’s true. The sales leaders had the results of dozens of local bond issue elections memorized, because the outcomes of those elections determine where to focus on furniture sales to schools. The education division employs an anthropologist, a former ed tech startup leader, and a quantitative market analyst to research and scout emerging trends. An enormous amount of thought and strategizing goes into to the daily operations of the division—ask me about the handful of 6-hour business strategy sessions I was involved in—for the sole purpose of making quick decisions about ideas and directions when the time is right. When there’s a good new idea in play, the company runs with it.

Higher education… well, let’s just say we’re not well known for our agility. You can choose any number of examples: The glacial pace of academic publishing. The endless committee hashing and rehashing of simple curricular proposals. Our eight-month long hiring processes. Getting IRB approval.

Certainly, there are items in higher ed that require due process. And we value collaboration and shared governance, and that necessarily requires more eyes on, and discussion of, whatever it is we are governing.

But how much is enough, and can we do better on certain things? I will end this by humbly suggesting that there are ways we can be more agile in higher education, by looking to the best practices of the best companies, without sacrificing who we are. For example:

- We’re really big on strategic planning in higher education and having long-term vision, but how much do we emphasize peripheral vision—looking around and not just forward to research, dialogue with, and learn from other kinds of industries other than higher education, and to scout out the potential disruptions to higher ed and get ahead of them? Shouldn’t there be a person or part of a university tasked with this?

- Could universities skunkworks groups within themselves and give them the ability to follow their ideas with less red tape? Yes, this means less faculty governance, but for a small sub-organization—could that be OK?

- In what ways within our existing structures can we make more streamlined paths for good ideas that need to see the light of day sooner rather than later?

As I finish this year with Steelcase, I'll have the summer to transition back into being a faculty member. Come August, I'll have students, grading, course preps, committee meetings and all the rest, just like before.

Except, it won't be just like before.

For one thing, I cannot look at classroom spaces anymore without analyzing their design. But also, I've been immersed in a workplace culture that, frankly, is sorely missing from much of higher education, where intellectual energy permeates the environment and there is a deep mutual investment between the company and the people who work for it—and I won't be satisfied with anything less in my own department and university.

I've seen how some of the great companies deal with thorny problems that are not all that different from some of the ones we deal with in higher education—and I'll be wanting to adapt the processes that work in business to the problems we face in education.

Finally, I've decided that, at least in my own mind, I am going to hang on to my official title at Steelcase: "Intern, Exempt." Although I'm now a tenured full professor, there's something appealing about being an intern: working under the radar, getting things done, helping others do excellent work and contributing to the success of my department and university without seeking glory or prestige.

We have a difficult job in higher education, and we need all the help and all the humility we can get.