At Inkster Preparatory Academy outside Detroit, students track their scores on the high-stakes NWEA Map test on the walls of their classrooms. Their names aren’t on the board—instead they have their own code—but at a glance they can see how well their peers are doing. The practice is known as “data walls,” and is designed to serve as a motivational tool. Students are told that “everyone is working to move their number” even higher, says Demetria Tumpkin, a second grade teacher at the school.

At South Newton Elementary School In Newton, N.C., educator Rebecca Vass, who teaches informational technology with science and social studies integration to fourth graders, uses a data wall so her students can track their progress on a quarterly benchmark assessment the district uses. Scores are color-coded by class, and students’ names aren’t attached to the data (nor do they have a unique code). That allows her to see data trends from one class to another. Vass says typically, her data walls aren’t tied to individual students.

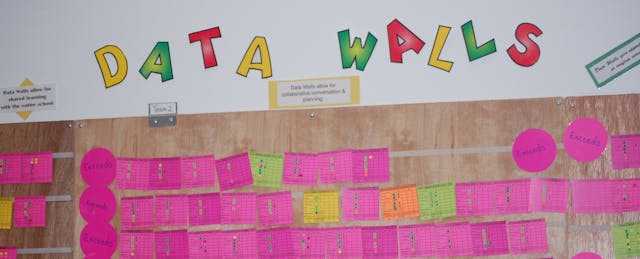

Perform a Google image search for “classroom data walls,” and you’ll see many examples of how teachers are displaying kids’ scores and results in the classroom. As the school year gets back into swing, teachers might be already planning their own student-facing data walls, perhaps with student names attached. However, the practice has its share of critics, who believe publicly displaying results does more harm than good.

Are They Effective?

One such critic is Launa Hall. Back when she was a third grade teacher at a school in Virginia, Hall put up a data wall in her classroom. But the data wall, which tracked students’ scores on state standards, didn’t stay up for long.

Hall, who chronicled her experience for the Washington Post back in 2016, wrote that the first morning after she put up the data wall, one of her students had a negative reaction. She “lowered her gaze to the floor and shuffled to her chair” after she saw where she was placed on the math achievement chart, she wrote. Since then, Hall has come to believe that the “public marking of where people are” is ineffective.

“It doesn’t give them the actual tools to fix the problem,” she says.

And what’s more, she doesn’t think public displays of their data tells students anything they don’t already know about their performance. Instead, she says data walls emphasize the wrong thing.

“We need to be emphasizing what the child is doing right, and what the child is doing great, so that we can build on those strengths and help that child make progress, versus spending time with the comparisons,” Hall says.

Motivation

Julie Marsh is a researcher at the University of Southern California’s Rossier School of Education. She has studied the use of data in schools, including data walls. Based on the interviews she’s conducted with educators in her research, she thinks many proponents really believe data walls are a positive thing that motivate kids. In particular, she has studied their use at the middle school level.

“We heard a lot that kids at this age like competition, and so knowing how you do relative to another person or another classroom might motivate you to kind of try harder and take more seriously the assessment,” Marsh says.

Marsh explains that some literature does suggest that data walls can motivate certain kids, in particular, those who are high performers. However, she notes that there is not a lot of research that suggests that data walls can be positive for kids who are low performers.

Marsh looks at the effectiveness of data walls through lens of previously-conducted research on motivation and goal orientation. There is a difference, she says, between performance orientation (your achievement relative to others) and mastery orientation (achievement relative to where you started).

“I think the public display of data allows for students to compare themselves to others—in some ways, [it] promotes that performance orientation,” Marsh says. “And some of that research actually suggests that a performance oriented goal could be really associated with negative outcomes for kids.” While some kids might be motivated by seeing how they compare with peers, she says, others might simply concede it’s difficult and give up.

By contrast, research has shown that a mastery orientation is often more associated with positive outcomes for kids.

“If you give the kids the data individually, privately, relative to either where their baseline was or where the standards want them to be, that would foster more of a mastery orientation,” Marsh says.

But what about the route Inkster Preparatory has taken, where student names aren’t attached to the data? Marsh says while that might alleviate public embarrassment a bit, individual students can still see their score relative to others, and compare themselves.

Hall, the educator who briefly flirted with data walls in her classroom, is skeptical of the practice of using numbers or other codes in place of names. “The kids get that figured out in a hot minute,” she says.

Tumpkin, the teacher whose school uses data walls in every classroom, says her students do talk about their scores. However, she notes that even if students identify who’s who on the data wall, the class has conversations about how their minds work in different ways—a concept related to growth mindset.

“Just because your number is in this color red, doesn’t mean that you can’t move to the next color,” Tumpkin says. “Your goal is to move on your own to the next color by working hard, asking questions and following through with the homework and different activities that we’re doing in school.”

Vass, the teacher in North Carolina, says students typically know where their dot—or score—is placed on the chart, and if they don’t remember, they can typically refer back to their student data notebooks, which keep information on things including personal goals and test scores. She says whether or not students talk about their scores is up to them.

Potential Trouble with FERPA

Some privacy experts say that data walls can violate FERPA because they publicly display certain student data. Nicole Snyder, a lawyer whose areas of practice include special education and general education law, writes to EdSurge in an email that data walls could potentially violate the federal privacy law, depending on the “information detailed on the wall itself,” such as student names, as well as “whether the parent has requested an opt out of directory information,” which limits what a school can share about a student.

“Particularly if it highlights a student’s exceptionality or if codes can be traced to specific students, a school district may face claims that the district violated applicable federal or state regulations, including but not limited to FERPA,” Snyder adds.

The walls may also run afoul of state laws. Kim Nesmith, the data governance and privacy director for the Louisiana Department of Education, has first-hand experience working with data at the state level. She tells EdSurge that data walls could potentially violate Louisiana’s Student Data Privacy law “in the same way that they could violate FERPA. The data could be linked to an individual student.”

However, even if a particular data wall does violate FERPA, Cameron Clark, a legal fellow at the Southern Poverty Law Center, notes that parents can’t sue the school district or an individual educator. “A scorned student or parent can’t sue for a FERPA violation.”