Students and teachers were not the only ones to return to class this week.

Nearly a thousand of the education industry’s C-level executives, private equity fund managers and investors gathered at BMO Capital’s “Back to School” conference in New York City. On their syllabus: networking and identifying the latest market trends in the education industry that can drive a company’s growth—and, of course, financial returns.

If ASU+GSV Summit is the edtech industry’s playground for dealmaking, this is the VIP club for its financiers. Few, if any educators were present (ironic, given the back-to-school theme). Instead, bankers and financial analysts showed up in full force. Early-stage education entrepreneurs were also in short supply; word in the halls was that private companies were expected to be making $15 million-plus in revenue to get a formal invite.

The Big Picture

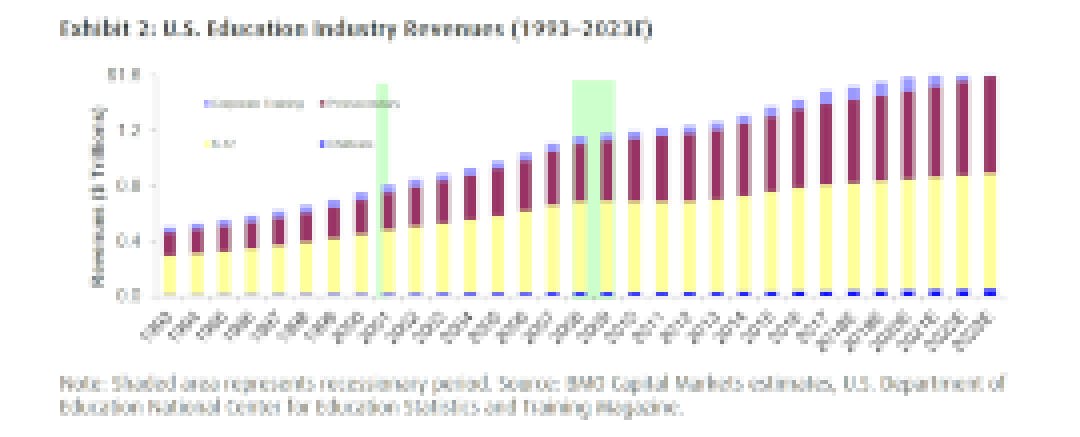

The conversations and company showcases revolved around the market opportunity in the education industry, and geared towards convincing financiers to dip their hands into the pot. In its latest market report, BMO estimates that $1.52 trillion will be spent on U.S. educational services in 2018 across childcare, K-12, postsecondary and corporate training sectors.

Now in its 18th year, the conference’s programming reflects a shift in public markets, says its organizers. At the turn of this century, most publicly-traded companies attending the event were operators of for-profit colleges and universities. But scrutiny and revelations of predatory malpractice have “left public investors with a sour taste about that sector,” says Jeff Silber, managing director and senior research analyst at BMO and an author of the report.

These days, the public companies in attendance tend to be education technology providers, says Silber. He expects more to come. “We’re going to see more IPO,” he adds. “My guess is if we’re here 3 or 4 years from now, some of the companies that I’ve been talking to will be public companies. I think investors’ appetite for a publicly held education company, specifically in the technology space, is present.”

The report also notes a steady climb in the number of mergers and acquisitions across the education industry.

Private equity-backed rollups of education technology companies have become recurring headlines. That’s not a new phenomenon; in earlier decades many private-equity firms also invested in for-profit college businesses. Today, most have switched their focus instead on on education technology products. “There are tons of companies that are small-scale, but you’re getting enough of them that are getting large enough and combining with others that private equity firms are investing in.”

Often, private equity firms say they want to build a “platform” of complementary tools that make it easier for customers to access and deploy multiple services at once. But the question remains whether these assets are integrated at the product and technical level—or whether these firms are simply buying a collection of brands that then get re-packaged and sold to the next buyer.

Should these companies aim to list on the public markets, “public investors are going to be looking for outcomes-based metrics, because today you have to prove that you’re improving outcomes,” says Silver. “If you simply just package a company, that’s more like financial engineering, and it’s going to be tough to sell.”

‘Crazy’ Rich Asians?

Whether it’s through investments (like a $500 million fundraise for VIPKID) or acquisitions (like NetDragon’s acquisition of Edmodo), the Chinese appetite for education technology assets has not gone unnoticed—especially by investment bankers.

Susan Wolford, head of technology and services business at BMO, quips: “On the sell side, we now anticipate in every transaction [the question]: ‘How about those crazy Chinese buyers?”

Many Chinese education companies that go public choose to list on the Hong Kong stock exchange, as it creates a smoother path to transactions, say the investors on her panel. Expect most of that capital to be invested outside of China. (EdSurge has chronicled how Asian dollars fuel U.S. edtech investments.)

American companies have tried going abroad to Asia before, sometimes as partners with on a joint venture. But they’ve enjoyed limited success. “U.S. companies are under-executing” on the opportunity, claims John Rogers, education sector lead at The Rise Fund.

Still, the opportunity is not stopping companies like Imagine Learning and Mathnasium, which have launched operations in Vietnam.

“The single largest megatrend is the rise of the Asian middle class,” claims Kosmo Kalliarekos, managing director of Baring Private Equity Asia. “The massive expansion of hundreds of millions of private payers, not the government, is changing the landscape of education.” Estimates from philanthropist Michael Milken suggest that Asian households spend upwards of 15 percent of their income on supplemental education services (versus 2 percent for U.S. families.)

Is It Core? Is It Supplemental? (Does This Matter?)

To sell into schools, curriculum developers focus on going after one of two pots of district funds: core materials (like textbooks) and supplementary tools (like educational games). Much of their sales strategy revolves around a district’s budget for these materials. In years past, digital providers have pursued funds in the supplemental category, as their tools were considered “point solutions” that focus on addressing a few needs.

There is some flexibility in states like Florida and Texas, says Sari Factor, CEO of Edgenuity, where there is “flex” funding that allows buyers to spend some money earmarked for core materials (like textbooks) on supplemental tools.

But over in the classroom, the lines in how teachers actually use core and supplemental materials have become blurred. “In the classroom, teachers are asking, ‘What is it going to take to deliver to students what they each need?’” says DreamBox CEO Jessie Woolley-Wilson. “What’s happening in the classroom is pragmatic and practical.”

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt’s Chief Learning Officer, Rose Else-Mitchell, acknowledged that “in the past, core companies like us are slow to innovate.” Bethlam Forsa, president of Pearson, added: “In the past, the main publishers used to have a pretty good-sized supplemental division...But we abandoned them. And it opened up white space for a lot of players to come in.”

Publishers aren’t sitting idly, though. Else-Mitchell and Forsa both say their companies are adding assessments and analytics into their digital offerings. They say that data from students using the tools can help drive continuous refinements to their products.

On a different panel, Accelerate Learning CEO Vernon Johnson offered this observation: “More and more teachers are DIY-ing it. When they close the doors, they’re building a collection of the things they like and work for their kids.” He later added: “Atomization and modularization...that’s important to the marketplace because that’s where it’s going.”

Yet too many tools also pose a challenge. “You’re going to walk into a classroom, and a teacher is going to be using a bunch of products, with 50 or 100 logins,” says Jamie Candee, CEO of Edmentum. “If you’re a provider, you have to understand everything else [teachers] are using in the classroom, and how your program is going to intersect.”