As America’s classrooms become increasingly connected, the nation inches ever closer to reaching a major milestone: 100 percent of schools with high-speed internet access, defined as at least 100 kbps (or 100 thousand bits per second) per student.

But what was once the gold standard for high speed is now barely enough to keep pace with modern learning environments, according to Evan Marwell, CEO of the nonprofit EducationSuperHighway, which released its annual State of the States report Tuesday.

While EducationSuperHighway works to connect the remaining 2.3 million students who lack internet access, the nonprofit is also looking ahead to the future, when 1 Mbps per student becomes the new broadband benchmark.

At that speed, Marwell said, “digital learning” takes on a whole new meaning.

“It’s really about the pervasiveness and frequency of use,” he said. “At 100 kbps, you can have a few teachers here and a few there at any given time using digital learning in the classroom.

"The big difference 1 Mbps makes," he added, "is you can really use digital learning in every classroom every day—without going back to the days of the spinning wheel.”

About 28 percent of school districts have already achieved 1 Mbps per student, including 15 percent of the 1,000 largest districts in the country—leaving 72 percent of districts without sufficient internet speeds to make digital learning a central part of the curriculum.

Nearly half of rural, single-school districts, which average about 200 students apiece, have already reached the 1 Mbps goal. So while those schools may not be able to offer the vast array of classes that their urban and suburban counterparts can, “they’re embracing digital learning as a way to level the playing field,” Marwell said.

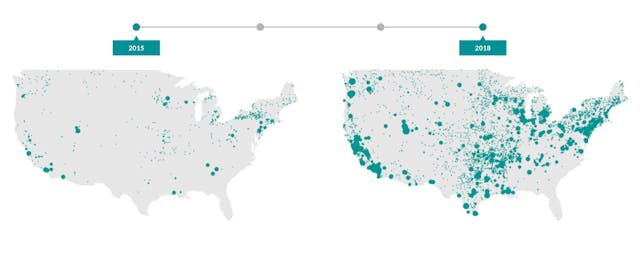

Since 2013, the number of U.S. students with access to at least 100 kbps of broadband has increased from 4 million to 44.7 million. Put another way, 98 percent of school districts have internet access, according to the 2018 State of the States report.

This widespread, existing broadband access in schools has led many to turn their attention toward the 1 Mbps connectivity standard. But the fact remains that 2.3 million students still can’t get online at school, which puts those students at a serious disadvantage.

The good news, Marwell said, is that 1.9 million of them are concentrated in 62 school districts—the vast majority of which can upgrade their broadband at no additional cost through “peer deals.” In other words, those districts can tap into an existing deal for internet service that other districts in the state are using, without having to fork over more money for broadband. That alone would enable U.S. school districts to reach the 99 percent connectivity goal.

For the other 400,000 students, however, it’s a bit trickier. “We do need these districts to say, ‘This is important, and we need to spend a little bit more money on internet access,’” Marwell said. But even then, the difference amounts to an average of less than $1 per student per year.

The broadband progress districts achieved in the last year is greater than EducationSuperHighway had projected. Last year, when 94 percent of districts had access to high-speed broadband and 6.5 million students remained without internet, the group hoped to get the latter measure down to 3.5 million by today.

The major gains recorded in the last five years can be attributed to three major factors, Marwell said.

First, state leaders supported the mission and helped drive it forward. Forty-nine of 50 governors made school broadband access a priority in their state (Kentucky, which has independently reached 100 percent school connectivity in the state, is the only state that abstained). “If they hadn’t stepped up, we might still be trying to convince people 100 kbps is important,” Marwell said.

Second, schools had to get the “right infrastructure … for highly scalable connections,” Marwell said, referring to fiber networks. E-rate modernization in 2015 made it possible for about 83 percent of districts to upgrade their Wi-Fi; prior to modernization, only about 14 percent of districts could do so.

Finally, and perhaps most significantly, broadband prices have dropped dramatically. Since 2013, they’ve gone down 85 percent, allowing schools to afford better broadband without actually having to spend any more money on it.