A consortium of 25 universities unveiled a new platform last month that will pull in information from systems across campus to bring richer analytics to college classrooms.

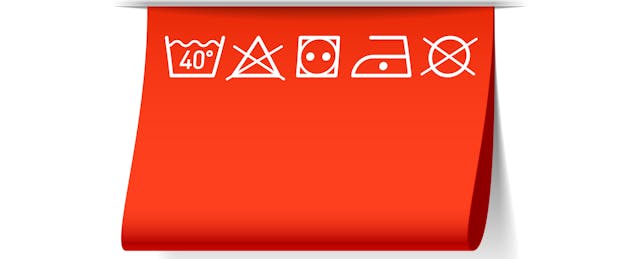

But its leaders have found that getting all the data into a form that professors can actually use presents a messy challenge, requiring what one project leader is calling “data laundry.”

To be clear, this is not data laundering, which would suggest that information is being whitewashed to make it seem more positive. Instead, the group says it is working to do the boring but important work of standardizing and organizing information so that it can be analyzed to help with things like student-retention efforts.

The consortium running the data platform is called Unizin, and so far five campuses in the group are working on this data scrubbing: Indiana University, Ohio State University, the University of Iowa, the University of Michigan and the University of Wisconsin at Madison. But they hope to create a process that others can use, and to push edtech companies to more closely follow standards so that there’s less cleaning work needed.

That way, colleges can one day have a dashboard that includes information from learning-management systems (LMS), student records, online-textbook platforms run by publishers and from the many tools that professors use, such as clickers.

“If you want to be data-driven in any meaningful way, your ability to do that is going to depend largely on the quality of the data you’re working with,” says Etienne Pelaprat, chief technology officer at Unizin.

Handing Over Datasets

The first hurdle has been convincing tech companies to share the data at all.

“There are a lot of third-party tools that people use with an LMS—some of which essentially act like an LMS—and we don’t have any insight into what’s happening inside that third-party app other than the grades that come back,” says Drew LaChapelle, a system analyst in academic technology at the University of Minnesota, which is a member of Unizin. “All of those are captured by the vendor, and they don’t usually share them with us.”

Unizin has worked to leverage the collective buying power of its members, all of which are large universities. The group has negotiated joint licensing deals with several software companies in the past few years, and in all of those deals it has required the companies to give college customers access to data created by their users. And Unizin requires companies to follow technical data standards called Caliper Analytics, developed by a nonprofit group called IMS Global.

“We’re gaining influence with vendors and making them understand that they have a critical place in higher ed,” argues Annette Beck, director of enterprise instructional technology at the University of Iowa. “Doing it as a consortium makes us really influential. Numbers speak. But are we going to always get everything we want? No.”

Locking Down Data

Some Unizin members have held back on trying the new data platform for now, in part over security concerns.

The group recently hired an “assurance officer” who is working with campus security officials to develop policies that govern how data in the system is handled and protected from potential hacking attacks.

“We’re ingesting a lot of sensitive data,” says Pelaprat, of Unizin. “Some institutions are still waiting for those policies to be developed.”

And even after the data is gathered and cleaned, colleges are still in the early stages of developing tools and strategies to make use of the information in classrooms.

Not everyone in higher education believes that all the work of amassing this data will be worth it, and some worry that too much focus on bean-counting will actually reduce the quality and vitality of college teaching.

Pelaprat argues that colleges are simply in the early stages of learning what can be done with learning analytics, and that one goal of the data platform is to enable research and experimentation. If the system works, it could allow colleges to do experiments that span campuses that were not possible before.

“A lot of the skeptical views of learning analytics point to the massive volumes of data that can be generated and the relative poverty of successful interventions that are data-driven,” says Pelaprat. “The capture and use of data is going to co-evolve with practical teaching and learning practices.”

In other words, teaching may look very different as professors learn to incorporate real-time data. “One is going to shape the other,” he argues.

Unizin has faced criticism since it was founded in 2014 for high fees charged to member universities and questions about its focus. But at a meeting at the University of Minnesota last month, several college leaders who work with the group said the data platform is an example of the consortium’s maturation.