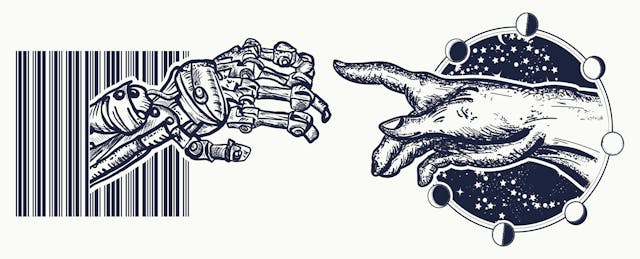

For those keeping count, the world is now entering the Fourth Industrial Revolution. That’s the term coined by Klaus Schwab, founder and executive chairman of the World Economic Forum, to describe a time when new technologies blur the physical, digital and biological boundaries of our lives.

Every generation confronts the challenges of preparing its kids for an uncertain future. Now, for a world that will be shaped by technologies like artificial intelligence, 3D printing and bioengineering, how should society prepare its current students (and tomorrow’s workforce)?

The popular response, among some education pundits, policymakers and professionals, has been to increase access to STEM and computer science skills. (Just consider, for example, the push to teach kids to code.) But at last month’s WISE@NY Learning Revolutions conference, supported by the Qatar Foundation, panelists offered a surprising alternative for the skills that will be in most demand: philosophy, ethics and morality education.

“Moral judgment and ethics could be as revolutionary as artificial intelligence in this next revolution, just as the internet was in the last revolution,” said Allan Goodman, president of the Institute of International Education. His reasoning: those building technologies that can potentially transform societies at scale may be the ones who most need a strong moral grounding.

Take the example of self-driving cars, said Keren Wong, director of development of RoboTerra, a robotics education company. She called attention to the “Moral Machine,” an ethical quandary posed by MIT professor Iyad Rahwan. The dilemma goes as follows: an autonomous vehicle is in a situation where it must make one of two choices: kill its two passengers, or five pedestrians.

Both options are tragic, but speak to a reality where technologists must program machines that make decisions with serious implications. “If we are leaving these choices in the hands of machine intelligence, then who are the people who will be programming these decisions? Who are the ones that are going to be setting up the frameworks for these machines?” asked Wong.

The push to develop and apply artificial intelligence technologies has also naturally raised concerns over automation, and the impact on jobs and employment. (See driverless trucks, for example.) But should tasks that can be automated, be automated simply for the sake of business efficiency?

That’s a question that Patrick Awuah, founder and president of Ashesi University College in Ghana, has wrestled with. “Humanity has always worked, and employment is not only about earning a living. It is also a sort of social enterprise where we engage with other people,” he said. “When we educate people in AI and the technologies of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, should those engineers and scientists be designing machines specifically to replace human work?”

Awuah, a MacArthur Fellowship recipient, continued: “If humans are designing machines to replace humans, versus helping them get work done, then that will change the structure of humanity to something that we have never seen. I’ve not read any history books where whole societies were not working. This is why it’s so important to have history and philosophy as part of the curriculum for somebody who's being educated as an engineer.”

In the United States, increased interest in technology and computer-science related career has correlated with a precipitous drop in the proportion of humanities majors at colleges. For Goodman, that’s one of his biggest worries for the future. “We’re entering a time when schools are eliminating programs in humanities, and philosophy departments are becoming an endangered species.”

“We need to be educating people so they are productive and employable,” Awuah later added. “But we also need to be educating people so that they’re creating a society that is livable and social, where human interaction is important.”

Still, he recognized that local technical expertise must be nurtured so that people can tackle challenges specific to their community. He noted that the combination of climate change and population boom will raise a host of agricultural problems across Africa. “We need local people addressing problems that are relevant to Africa, problems that will not be solved by scientists in other parts of the world.”

Panelists also emphasized the need for children to be equipped with the mindset and confidence to pursue learning throughout their lives. Only then, they concurred, can future generations stay ahead of the curve of whatever changes are wrought by technological advancements.

Students “need to be able to understand and deal with the fact that change is constant. That’s the nature of the world, and that’s the nature of what technology brings,” said Goodman.

Anthony Jackson, vice president of education at Asia Society, underscored the importance of “adaptability.” For him, “there is no doubt that the ‘new’ things that we teach today will be obsolete 20 years from now, and then our students will need to be learning yet another set of new skills. If we teach people in such a way that they are able to learn throughout their lives, they will be retooling and re-learning as things are changing in the world.”