How are rural schools, which face logistical obstacles unheard of in more urban districts, finding ways to provide their students with technology? If one Alaska district is any indication, it’s through a combination of creative problem solving and technology.

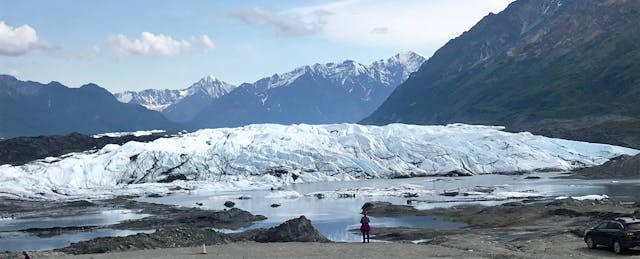

Matanuska-Susitna Borough School District is the second largest district in Alaska after the Anchorage School District. It serves approximately 19,000 students spread over an area the size of West Virginia. Its 47 K- through 12-grade schools range from the tiny 19-student Beryozova School, which serves what is known as an “Old Believer” community of families with Russian heritage to a typical 1,200-student high school.

The access to technology that students have is just as varied as the students and schools themselves. Some students live off the grid, in homes only reachable by four-wheel drive vehicles. Others live in familiar American suburbs. After conducting a survey in 2015, district leaders found that while a surprising number of students have access to broadband, the biggest obstacle to technological access rural students face is the lack of devices.

To provide better access for the students of the Mat-Su district, leaders there created the Rural Enhanced Access initiative. The program is run by Justin Ainsworth, Director of the Office of Instruction and his team of 5 at the District’s Office of Instruction, including Jeffrey Blackburn, an Educational Technologist . One unique aspect of Mat-Su’s approach to digital learning is that edtech is housed under the office of instruction. This means that decisions on education technology are being made by certified teachers with experience and that the classroom was at the forefront of every decision made. They work closely with the district’s IT department to implement the policies.

The program uses school resources to purchase Google Chromebooks for students in rural areas (as the name implies) and couples that with a blended learning strategy in the classroom. With the ultimate goal of going 1:1, the district started with a pilot program of 9 schools and 1,200 students.

The plan they devised was simple. Flipping the traditional script of starting with the “core” schools, Mat-Su leaders looked to the edges of their district. They focused on the smaller, rural schools because these were both most in need of access and had the smallest student bodies. Fewer students meant that the roll outs would be simpler and district leaders could learn from any missteps before scaling up the program at larger schools. Ainsworth and Blackburn offered training to administrators before the school year started, and provided professional development for teachers onsite at the schools, pulling them out for a couple of days for intensive instruction.

The results of the program’s first year — and community feedback—were positive. The next year, the program was extended to five more schools, and just this fall, it expanded to another three schools.

Since implementing Chromebooks and the blended learning strategy in the district, student performance metrics across the board have risen. Graduation rates this year are projected to reach an all-time high of 83 percent, and language, reading, and math scores on standardized tests are up at almost every grade level. Beyond that, the program has spawned a few incidental by-products. For example, Girls Who Code has worked with the district to start 27 coding clubs—something that would have been unthinkable before. While Ainsworth is reluctant to attribute all of the increases to the technology initiative, it is sure to have played a part.

Three Lessons Learned from the Program

Ainsworth and Blackburn shared three key takeaways from their experience of launching the program:

1. Go Where the People Are

One of the biggest challenges the district faced was logistics. How could they get the technology and training into the right hands with their schools spread over such a wide area? Something as simple as asking teachers to come in for a training session could mean many hours of driving or even an overnight trip—and all the extra expense that goes along with it. So instead, they brought the learning to teachers. The edtech team spent weeks going around to various schools to provide on-site training.

This spirit of proactive facilitation extended beyond physically coming to the teachers. The program itself was completely voluntary. This wasn’t a push from the top down. Instead, the district’s edtech team reached out to those teachers who expressed interest in the program. The result was that teachers were engaged in the process. Blackburn and Ainsworth credit this as one of the program’s strengths. By focusing on the teachers who were already on the path to personalized learning, they found willing and enthusiastic early adopters who then became evangelists within their own schools.

As the program grew, they faced a new problem: there was no budget for more IT staff to meet the growing demand that the new technology brought. To deal with the rising tech support demand, teachers began to train as “digital first responders,” providing local on-site support for other teachers and assisting them with tier-one tech support, such as resolving password and login issues, installing and uninstalling programs, and helping teachers navigate unfamiliar applications.

2. Have a Bias Toward Action

In part due to the culture of independence in Alaska and in part due to the realities of working in such a geographically spread out district, edtech leaders focused on actionable steps over meticulous planning. That’s not to say that there wasn’t planning—the scope and success of the project is proof of that—but that where actions could be taken, they were. Similar in many ways to the agile development model, the team built a minimum viable program, sought feedback from users (in this case, educators), and iterated to improve as they went along.

3. Focus on How Technology Serves the Teaching

Blackburn credits the success of their onsite training with getting teachers on board for the program.The best way he found to accomplish that was focusing on the instruction techniques that technology could support, and not on the tech itself. “This was a very intentional thing for us. This [technology] is a tool to amplify the best practices that have been proven over decades, not to replace them. Take those things that you know are good and use the technology to amplify them,” said Blackburn.

What’s Next for Mat-Su?

Ainsworth and Blackburn are looking forward to the next iteration of their program. "As we move toward the core area schools and the cost of going 1:1 rise, we are looking to focus on specific content areas,” says Blackburn, starting with math and moving on from there.”' And as the program matures, they intend to dig into what resources and tools are working best for their teachers and students. That type of analysis will allow them to make the right moves going forward and continue expanding the program to meet the needs of their district.