Over the summer, academics debated the impact of growth mindset, the belief that one’s intelligence can be developed with hard work and effort, and whether it can move the needle on academic performance. Even Stanford psychology professor Carol Dweck, who is often credited with the term, chimed in with additional research supporting the efficacy of mindset interventions.

An Education Week survey found that the vast majority of educators believe that a growth-oriented mindset can help improve students’ motivation, commitment and engagement in learning. But the study found that applying those ideas to practice, and helping students shift their mindset around learning, remains an elusive challenge.

Those findings largely coincide with my observations as an administrator, coach, technology implementer, and now founder of an education company. Over the summer, my team ran a series of professional learning community sessions with dozens of educators across the country, focused on instructional practices that foster and support growth mindset. At these events, almost all teachers said they get the big ideas around growth mindset, but over 80 percent said their schools don’t implement them well.

The fallacy of the one-time intervention

In her post, Dweck offered evidence of effective one-time interventions that “last about an hour and cost less than $1 per student.” These often take the form of short, teacher-led or online lessons; students learn about how the brain grows with effort, complete short writing exercises, and share what they learned with peers.

I have found that these one-time lessons are necessary, but not sufficient, to shift student mindset in a meaningful way. At my last school in San Jose, Calif., we barraged our students with growth mindset lessons during the first two weeks of school. They learned about neuroscience, shared personal examples and watched videos of famous failures. By the end of those two weeks, students could regurgitate back to me all the details: “Ms. Gupta, I get it. My brain is like a muscle and the harder I work it, the stronger it gets.” (That’s no longer considered a great metaphor, but it’s what the materials suggested at the time.)

Fast forward a couple of months, though, and those same students—in the tough moments of learning—would behave very differently. One student who had been effusive about the growth mindset lessons was struggling with two-step math equations. In his math class, I saw him get several problems wrong, push back his paper, sigh heavily and mutter, “I can’t do this.”

Skills that build a growth mindset

A comprehensive literature review from the University of Chicago Consortium offers a helpful framework that illustrates how students’ belief systems and behaviors fit together. Students with a growth mindset are more likely to demonstrate grit, show up to class and perform better academically. Furthermore, getting good grades reinforces student mindset. Students see evidence that their hard work is paying off and buy into the growth-oriented belief system.

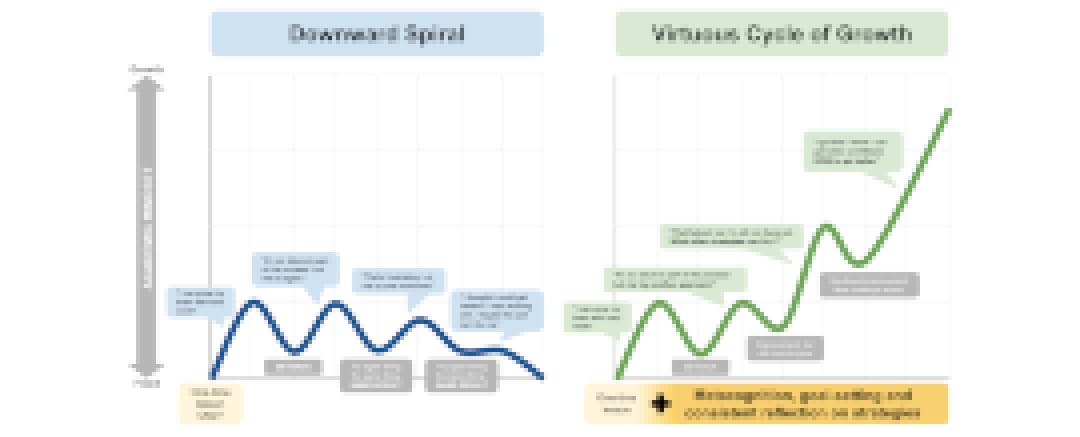

But what happens when a student doesn’t experience academic success? One can teach them growth mindset lessons all day long, but without personal proof that their effort translates to improvement, it just won’t work. I’ve seen it have the opposite effect: “I thought I could get better if I kept working at it. Maybe this just isn’t for me,” one student said.

The key to breaking this downward spiral is to insert new strategies and approaches into the picture:

One way to help students develop a growth mindset is to build the skill of reflective learning, which requires them to ask: What strategies are working best for me, and what are new ones I can try? One student may find a graphic organizer to be a helpful tool for citing evidence, while another prefers to highlight supporting points in different colors. Another might list every possible option for evidence, and cross out the weakest ones.

With consistent self-reflection, students identify and apply the right tactics in different contexts, see that new strategies and approaches can be developed, and learn how they learn best. Reflection is a skill that requires practice and feedback, just like anything else. An independent assessment of regular student reflections showed that pupils improved significantly over the course of one semester, and that improvement led to significant growth in academic GPA.

As educators, we can support this critical skill development by building a consistent routine for student reflections, giving timely feedback on them, and making sure they connect the dots between specific actions they are taking and growth. Most importantly, this needs to happen embedded in learning throughout the year (not just in first two weeks lessons or at report card time).

Growth mindset cannot be a label

In the University of Chicago Consortium study, the researchers acknowledged a gap in our collective understanding of how we improve practice around learning strategies. They wrote, “We could not find any studies of teachers’ practice in developing students’ learning strategies. This is surprising, given the important role of learning strategies in facilitating student understanding and improving students’ grades.”

We need experienced educators pushing and documenting their practice, more tools to support this skill-building (where I’m focusing my effort), and more research to evaluate and quantify impact.

I’ve also heard adults apply the language of mindset in ways that are concerning. I sometimes hear: “Those students aren’t improving because they have a fixed mindset, and they just give up.” It just so happens that “those students” are more likely to come from low-income families and underrepresented communities, per research published in the National Academy of Sciences.

We can’t use growth mindset as another label for students. We must help them build the skills that foster a growth mindset and fulfill their full potential as learners and contributors.