Raging wildfires in California and devastating hurricanes along the Atlantic seaboard have sent school officials scrambling to resolve immediate problems, such as repairing infrastructure and finding new schools for displaced students. Longer term, climate change may have a more permanent, major impact on the future of learning, according to a new report.

In “Navigating the Future of Learning,” a trio of futurists from the nonprofit KnowledgeWorks highlighted a handful of societal “drivers of change” that are likely to shape education during the next decade. Among them: demographic shifts, changes in the nature of work and climate volatility will all impact how tomorrow’s students will experience school.

These factors are a mix of what Katie King, a co-author of the report, described in an interview as inbound changes—“things that are happening to us, [where] we’re feeling the effects”—and outbound ones, which are “those actions we take [as humans] and the choices we make.”

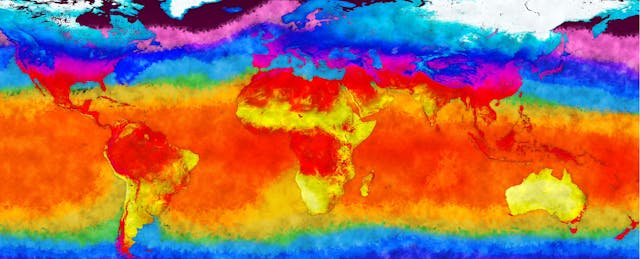

Climate shifts such as sea level rise or wildfires are presented as examples of inbound change—and they’re already a catalyst for human migration, says Jason Swanson, another co-author. “We’re seeing the very beginnings of this in the U.S. and certainly globally,” he says.

In recent years, schools in New Jersey, Florida, Puerto Rico and elsewhere have faced daunting relocation and rebuilding challenges following hurricanes and floods.

Inbound changes may also collide with outbound ones like migration caused by political instability. “How many tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of people have no country anymore and exist in refugee camps?” says Swanson, adding that population displacement is a reality we’re already facing. Predicting the number “climate migrants” over the next few decades is difficult, but the World Bank estimates roughly 140 million people globally could face displacement by 2050.

That means learning disruptions that could lead to a new concept of school. Displaced students may not have many options for school stability beyond growing options in online learning. But the authors offer examples of creative workarounds and solutions, as is the case at a new Santa Ana-Calif. high school, called Círculos.

The school has no fixed location, and “groups students in tight-knit learning circles comprised of peers, teachers and community members and embeds them in co-working spaces, mobile labs and the offices of partner organizations,” according to the report.

Change isn’t all bad for communities though. The report also notes that the future may provide cities with a chance at reinvention—especially places hard hit by declining industries and a new economy. Take Pittsburgh, a former steel capital, which is putting its focus on education through networking. There, Swanson points Remake Learning, an organization that connects various community organizations with schools and opportunities for students.

Traditional community revitalization efforts often do not translate into lasting change, the report cautions—and gentrification and investment attempts may become exclusive and actually exacerbate inequality and marginalization. By contrast, initiatives like the national Reimagining the Civic Commons are looking to revitalize public spaces through environmental sustainability and civic engagement, and may serve as ground-up alternatives.

The overall goal of these efforts are to create flexibility in the face of an uncertain future. “A major underpinning in all our work is that the future is not a fixed point,” Swanson says. To that end, the report is not so much a recipe for the future, as it is a prompt to get communities, schools and other stakeholders talking about how their visions may be shaped by social and environmental change.

“It’s meant to help people think about what’s possible and what they want,” King says of the report. “It’s an invitation to think about the future more often.”