For many U.S. cities and states, 2018 marked the wettest year on record. There was also plenty of rain in the education technology industry, where venture capitalists and private-equity investors unleashed a deluge of cash.

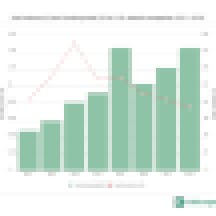

Last year, U.S. education technology companies raised $1.45 billion, matching the previous high for the single-year funding total of this decade, set in 2015. The funding total in 2018 also eclipsed the $1.2 billion raised by U.S. edtech startups in 2017.

There’s a notable difference between 2018 and 2015, however. In 2015 there were 165 deals, versus just 112 in 2018. And that dip in dealflow has been happening in recent years: Investors are pouring more money into the edtech industry, but across fewer companies. In other words, they’re cutting fewer—but bigger—checks.

One trend is clear: The dollars invested in the US edtech industry has ticked up steadily since 2011 (considering 2015 as an aberration).

On the whole, bigger but fewer deals is a trend common across all U.S. investment activity. Data from market analyst firms CB Insights and Pricewaterhouse Coopers show that total funding across all sectors increased in 2018 despite falling deal volume. Pitchbook tallied $130.9 billion in funding for U.S. venture deals, marking “the first time annual capital investment eclipsed the $100 billion watermark set at the height of the dot-com boom in 2000.” It also observed that “a high concentration of capital in mega-rounds attract the lion’s share of investment.”

This pattern is likely to continue into 2019. As the U.S. edtech industry matures, companies with demonstrable revenue growth are distinguishing themselves from the rest of the pack and attracting bigger funders higher up the investment ladder.

For edtech companies able to show consistent growth and revenue, that should be welcome news. Others may have cause for concern. According to Jason Palmer, general manager at New Markets Venture Partners: “2019 will be an important year of rebalancing in the edtech market. There will be a handful of big winners, but a large number of losers—companies either going out of business, raising money or being acquired at rational valuations that are less than what they used to get.”

Venture capital is by no means a guarantor of success. As the New York Times recently profiled, some entrepreneurs are increasingly eschewing investors and the grow-at-all-cost expectations that can come with the money—and run startups to the ground.

2018 Edtech Funding Breakdown

In this annual year-end analysis, EdSurge counts all venture investments in U.S. educational technology companies whose primary purpose is to support educators and learners across preK-12 and postsecondary education. For 2018, we tallied a total of $1.45 billion raised across 112 deals that were publicly disclosed.

Breaking down investments by rounds, the lion’s share of the $1.45 billion total is concentrated in later-stage deals. Also notable is the continuing dip in the number of angel and seed deals, which have fallen from a peak of more than 100 in 2013 to less than half that number in 2018. That decrease correlates with the decline of edtech accelerators, which once helped spawn many of the early-stage startups during the early parts of this decade.

Still, plenty of capital remains for early-stage education startups. New money continues to emerge for seed deals, including university-affiliated funds and family offices. Over the years, the average size of seed rounds has ticked upward—and so has the bar for raising them. Where a proof of concept, a talented team and a few early customers used to suffice, investors now expect to see $500,000 to $1 million in revenue before investing in a seed round.

The era of easy money, marked by pre-revenue fundraises, is likely over for edtech companies. More common in 2010 and 2011, the early days of the current edtech investment cycle, those deals were prevalent at a time that saw an abundance of new ideas, companies and investments. Today, far fewer are getting funded on the “freemium” model, a proposition that has fueled the growth of startups like ClassDojo and Remind, but proved challenging for others like Edmodo.

Over time, as investors learned which business models worked—and which didn’t—some have fled the sector. Those who stayed have become selective.

Investment Trends

Breaking down the $1.45 billion invested in 2018, U.S. edtech companies that support K-12 students and educators raised $511 million, and those that primarily serve postsecondary education raised $590 million. Companies whose products serve preschool and professional learning sectors also raised $350 million (represented as the “Other” category in the graph below).

Higher Education & Post-Secondary

Post-secondary tools altogether saw a notable bump in funding. Leading the pack were CampusLogic ($55 million round in 2018) and Commonbond ($50 million), whose tools focus on supporting students and higher-ed institutions with financial aid services and loans. As concerns over student debt persist, expect interest in alternative solutions, like income-share agreements, to grow.

Closely tied to student debt is the question of whether college graduates can land jobs. Here, plenty of investors want to help build that bridge from education to employment. Trilogy Education raised $50 million to partner with college and universities to offer short-term workforce-training bootcamp programs focused on digital skills. Another company, Handshake, raised $40 million for its service that connects college students with employers.

“The lines between human capital management, corporate training and alternative certifications are blurring,” says Palmer. Case in point: Guild Education, which raised $40 million to continue working with companies, including Chipotle and Walmart, to create educational benefit programs where their front-line employees can get a college degree.

Expect to see more entrepreneurs and funders trying to connect the dots between schools and employers, says Chian Gong, a principal at Reach Capital. And despite the talk of technology “disrupting” higher education, colleges and universities have proven more resilient and flexible than they often get credit for.

Once upon a time, she notes, “MOOCs were supposed to displace higher education. Now many MOOCs are embedded within these institutions. Bootcamps were supposed to do the same; now many are becoming a part of higher education.”

K-12

In the K-12 sector, the biggest deal went to DreamBox Learning, courtesy of a $130 million growth equity investment from The Rise Fund, the social-impact fund attached to private equity firm, TPG Capital. The Bellevue, Wash.-based provider of an online K-8 math product has been around since 2006, but last year enjoyed a 40 percent increase in district adoption, according to John Rogers, who leads education investments for Rise.

Continued improvements in school technology infrastructure, in particular the “penetration of broadband and digital devices,” says Rogers, is making it possible for “best-in-class digital solutions to win in the market.”

Adoption is one cause for celebration. But questions remain whether these digital tools are being used. A report from BrightBytes published last fall found that the majority of app licenses purchased by districts were never used. Another study by LearnTrials found that 65 percent of licenses were never or rarely used by students.

“Those are very sobering statistics, and a signal that edtech still has a ways to go before we can pat ourselves on our back and say we’re moving the needle for teachers and students,” says Rogers.

Expect more focus on this issue in 2019, adds Palmer, as states report on their progress made towards their Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) plans, which outline what they need to do to receive federal education funding. “A number of states are now building into their ESSA plans a priority for understanding the efficacy of the technology platforms their school districts use,” he notes. And if tools aren’t being used, what’s the point of purchasing them?

Dry Powder Deals

No, we’re not talking about ski conditions. That’s the metaphor for having an abundance of cash for investment on hand, and a term several investors used to explain the growing interest from private equity in the edtech industry. (Estimates for the amount of dry powder for all private equity firms hover around $1.8 trillion, a record-setting amount according to some analysts.)

As in previous years, 2018 saw an influx of private equity-backed deals with established names in the education business. Francisco Partners acquired majority stakes Discovery Education and Renaissance Learning; CIP Capital did the same with Carnegie Learning. Another big growth equity funding round came from Great Hills Partners, which put $110 million in Connexeo, a provider of school administration and payment software.

Private equity-owned companies continued to snap up edtech assets, including Frontline Education (which made its 12 acquisition this year) and Turnitin, which bought AI grading startup, Gradescope. Imagine Learning, owned by Weld North Education, an education-focused private equity firm, acquired digital math company, Reasoning Mind.

Typically, private equity firms eye companies making at least $15 million in revenue, and will buy them through a banker-organized sales bid. A hot company usually nets a high acquisition price. But some firms don’t want to pay that premium, and instead seek smaller deals that don’t go through the bidding process, notes Troy Williams, a managing director at University Ventures, an investment firm focused on the postsecondary sector. He’s seen private equity interest in companies making less than $10 million.

Private equity-backed companies are “in a race to build bigger platforms,” notes Palmer. Case in point: Insight Venture Partners merged five education data companies into one, Illuminate Education, in July 2018. Schoolmint, which was acquired by BV Investment Partners in 2017, has also publicly shared its plans to piece together different edtech assets into one platform.

“It will be an interesting fight to watch between the legacy players and the upstart conglomerates like PowerSchool and Frontline Education,” says Palmer. “There’s a moment in the market now where publishers like Pearson and McGraw-Hill—the traditional 800-pound gorillas—may be supplanted by new, digital-first technology platforms.”

With plenty of “powder” and more revenue-proven companies, many investors see potent ingredients for mega deals in 2019.

Uncertainty at Home and Abroad

When it came to raising blockbuster rounds in 2018, however, U.S. edtech companies paled in comparison to their peers in Asia, home to Byju’s ($540 million), along with VIPKID ($500 million), Zuoyebang ($350 million) and Yuanfudao ($300 million). The sum of those four deals alone exceeds the entire U.S. industry; in fact, eight of the top 10 investment rounds worth $100 million or more went to Asian companies.

Seemingly flush with capital, Asian companies appear positioned to buy U.S. edtech assets. In early 2018, NetDragon, a Chinese gaming and education company, acquired Sokikom and Edmodo. But there have been fewer such deals than some may have anticipated. “At the start of [last year], there was a lot of interest and speculation that large, well-funded Chinese edtech companies were going to be a source of exits and growth opportunities for U.S. edtech companies,” says Reach’s Gong. “But that ship has kind of sailed because of political tensions at this point.”

Uncertainty over tiffs and tariffs between the U.S. and China (and the rest of the world) could “severely undermine” global merger and acquisition deals, according to analysts. Furthermore, rising scrutiny over China’s data privacy and surveillance policies have raised questions over how foreign buyers would protect user data, especially that of children.

Still, Asian companies are on the lookout for deals. Byju’s is reportedly in talks with U.S. companies about potential acquisitions. “I feel confident in that in 2019, we’ll see acquisitions of high-profile U.S. education technology companies by Asian edtech companies,” predicts Palmer. “If that doesn’t come to pass, it’ll be because the current trade war climate persists and gets worse.”

Domestically, early-stage U.S. investors are watching the economy with caution. “If there’s an economic downturn, angels, family offices and seed funds may invest more conservatively,” says Figure Eight co-founder Diana Anthony, since seed investments are often the riskiest bets in terms of potential payoff.

In addition, “the broader backlash against the tech industry—that is going to impact education and edtech as well,” adds Gong. As evidence of questionable data-sharing practices and cybersecurity breaches mount, so too have cases of compromised data systems at school institutions and education companies surfaced. Technologies from Amazon to Uber have inspired startups to apply those models to education. Today, edtech startups may want to reconsider using those analogies in their branding. A “Facebook for education” is just no longer in vogue as it was five years ago.