By most measures, Massachusetts is one of the nation’s highest-performing states when it comes to K-12 education. It ranks first in the country on lists from Education Week and U.S. News, and is singled out for its high reading and math achievement, as well as its relatively narrow equity gaps among different ethnic and socioeconomic groups in academic performance.

Yet to hear the state’s commissioner of elementary and secondary education tell it, there’s still a lot of work to be done.

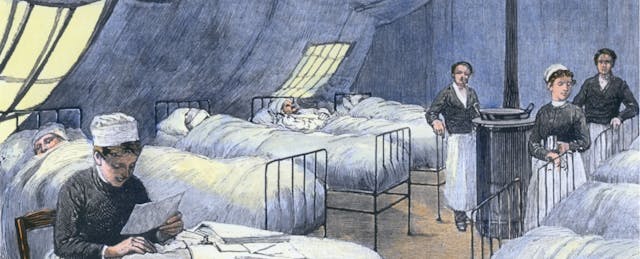

“Massachusetts has done very well,” said Commissioner Jeffrey C. Riley at the recent LearnLaunch 2019 conference in Boston. “But I think in a few years, this will start to look like 19th century medicine: Get your solder out, because the best we can do is amputate. Instead, we need scalpels.”

At LearnLaunch, Riley spoke at length about a variety of subjects, including the need for better teacher training, wraparound services and more freedom for innovation. What follows is a lightly-edited sampling of his remarks.

On Professional Development

The big secret in public education is that the variation in teacher quality is astounding. In America, it’s quite large. But in Canada the variation is much less pronounced. Why? Because they spend more time training their teachers, giving them the time and space to share lessons and take part in PLCs (professional learning communities). When I was teaching, there were all these conferences where teachers could go and share best practices. You could steal lessons and bring them back to the classroom. With the advent of No Child Left Behind, we’ve kind of lost that ability to share with each other. I think that’s a problem.

We need to do a better job of teacher prep, but mostly we have to do a better job when you start teaching on day one. Teachers are leaving within their first five years of teaching, and what that says to me is that we need a better retention approach inside the first five years to make sure people feel successful.

On Critical Thinking in Action

We talk about critical thinking, but what does that actually mean? I’ve defined it as using your skill set to encounter new and complex situations.

When I was a principal in Boston, we did a candy sale and sold chocolate bars. Along the way, I got a call from a local grandmother, who started screaming at me: “How could you do this? Are you out of your mind?” I said, “Ma’am, what are you talking about?” She said, “It’s your candy sale.” I told her that I thought every school in America did a candy sale at this point. She said, “That’s not what I’m talking about—it’s the price.” I replied that I didn’t think a dollar was too much to ask for a candy bar. She said, “A dollar? Your kids are selling them for five!” A student or two got in trouble that day—but that was very good critical thinking on their part.

On Innovation

Now more than ever we need innovation. We need to get people out in the field and get them thinking in new ways. In Massachusetts, there is a proposal to put money in a trust to do innovative practices. Harvard is very interested in creating an incubator, where educators can come in and try out their ideas and they would help do the data and study those ideas. I think we need to really push for that.

On Data

One area where I think things have been slow to move is with data. In particular, getting data systems to talk to one another so that we could have longitudinal data beyond what happens just within the K-12 space.

For example, take some of the research into early preschool projects. Kids got a preschool intervention, and it seemed like it went well initially—in elementary school those kids started to move up. But then the gains wore off as they went further along in elementary school. People thought that the preschool interventions were not that impactful. Except they tracked those same kids over time—over decades—and found those kids had higher IQs by age 15 and fewer incidents of incarceration. So what was initially seen as a failure was actually, longterm, pretty successful.

Right now, we don’t have our systems set up so we can marry that data and do those kinds of longitudinal studies. I’ve argued that there are golden needles in these haystacks of data that we don’t have access to right now, which could help us plot the way forward.

On Software

I think for a long time we we’ve been waiting for tech to be this amazing tool to help kids with instruction. It’s actually been a little slower coming than many of us would like. I think the tipping point has happened over the past five to six years. We’re starting to see things that actually work. In my old district, Lawrence Public Schools, we used ST Math. It’s all about how to teach math in a conceptual way versus a linguistic way, and that has helped a lot of our kids who are learning English.

On Advice to the Edtech Industry

If you have something of quality, it will spread like a virus. Teachers will walk over broken glass to get something that works in their classrooms. Find something that’s worthy of that. There is an incredible thirst for educators in the field to look at your products and see whether they might work for them.

On Measuring Student Potential

When I was a deputy in Boston, we did a performance of Godspell. We did three sold-out shows, three nights in a row. On the second night, we hosted a critic from New York and he looked at Michael, the kid who played Jesus, and told us after that if he keeps this up, he could be on Broadway in five years. His voice and comedic timing were beyond compare. What the critic didn’t know was that Michael was organically dyslexic. He was never going to be advanced or even proficient on an academics test. But there’s nothing wrong with Michael; it’s just that we haven’t chosen to recognize his gifts as something that is important for our children to do.

On Standardized Testing

In the ’90s the best test in America was in Maryland, the Maryland School Performance Assessment Program. It didn’t give individual results. It had kids working collaboratively on performance-based tasks, and they gave school-level results, rather than individual ones. With the advent of NCLB, every student had to have an individual score, and so Maryland completely scrapped this test, which even the teacher’s union said was good—just don’t use it in accountability measures. That was a pivotal moment in education in America. We lost something in this deeper learning.

On Wraparound Supports

Most juvenile crime happens between the hours of 2 to 6 p.m., when kids are unsupervised. We need to create more opportunities for kids to be engaged. With a few exceptions for schools that have extended learning time, we’re still on this 19th century agrarian model where our kids would go to school from eight in the morning to two in the afternoon and then have the summers off so they could go work in the fields to produce the harvest.

My kids go to Boston Public Schools; they are not producing the harvest in the summer. I think we need to start rethinking our structures. Does that mean we start to change our schools or add more wraparound services? What we need to see is both, but the need for more wraparound services is going to be more crucial now than ever before.