For a field that is dominated by women, there sure are a lot of male superintendents overseeing U.S. public schools.

It’s one of the most pressing issues facing superintendents today, according to leaders at the AASA, the School Superintendents Association, as well as one of the most glaring findings from this year’s superintendent salary survey.

That, and the fact that superintendents are overwhelmingly white.

“The lack of diversity in the superintendent role—it hasn’t changed as much as it should have,” says Deb Kerr, superintendent of Brown Deer School District in Wisconsin and president-elect of AASA. “The survey verifies we have some work to do, but we’re going in the right direction.”

The survey, distributed to AASA’s 13,000 members for the sixth year in a row, presents a picture of the gender makeup, racial and ethnic diversity and salary breakdown of education leaders in the U.S. This year’s study analyzes more than 1,400 responses.

Here are three takeaways from the survey:

Superintendents are disproportionately male

While women make up 77 percent of the teaching profession, according to the National Center for Education Statistic, they account for just 33 percent of U.S. superintendents, the AASA survey found.

Based on previous editions of the AASA study, the number of female superintendents is steadily—albeit slowly—increasing year over year.

Superintendents are overwhelmingly white

Nearly 90 percent of education leaders who responded to the survey are white, and the breakdown is fairly consistent for men and women. Ninety-two percent of male respondents were white, compared to 88 percent of female respondents.

The number of superintendents of color appears to be increasing, but the pace of change is slow. In the 2017-2018 study, 93.3 percent of respondents self-reported white, compared to 89.9 percent this year.

Beyond those who are white, another 3.3 percent (47 individuals) responded as black or African American, 2.7 percent (39) said they are Hispanic or Latino, 1.2 percent (18) said they are American Indian or Alaskan native, and 0.4 percent (6) said they are Asian. Due to the small sample size of these racial and ethnic groups, it’s difficult to say whether they accurately represent the whole of superintendents in the U.S.

These numbers are not where the AASA wants them to be, Kerr tells EdSurge, which is why the organization has developed programs to recruit and train women and people of color who will eventually become education leaders.

“I feel like we’re trying to fill a void,” Kerr says. “There’s a definite need, and we’re doing what we can.”

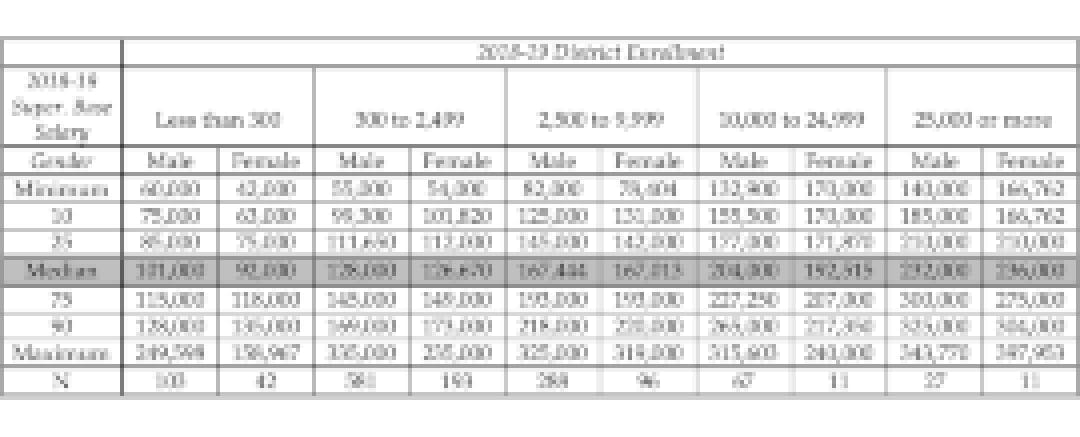

Salaries range from $42,000 to $400,000

Though the median base salary for male and female superintendents is reasonably consistent, the salary floor for women is lower and the ceiling for men tends to be higher.

For example, the lowest-paid female superintendent for a district serving fewer than 300 students reported a $42,000 base salary, while the lowest-paid male superintendent in the same district subgroup earned a $60,000 base salary. The highest-paid females in that category earned $158,967, compared to $249,598 for the males—more than a $90,000 difference.

The majority (54 percent) of superintendents work in districts that serve between 300 and 2,499 students. In that district subgroup, the lowest-paid female superintendent makes $54,000 per year, just $1,000 less than the lowest-paid male. However, the highest-paid female leader earns $235,000, exactly $100,000 less than the highest-paid male.

The highest-reported salary in the study, however, belongs to a female superintendent overseeing a district with more than 25,000 students—the largest district category. She earns a base salary of $397,953.

Kerr attributes the salary disparities to school board biases against women and the research-backed theory that women are less likely than men to negotiate their salaries.

“Depending on the school board offering the salaries, they sometimes don’t realize women can do this job just as well,” she says. “It’s a gender-equity challenge we’re dealing with.”

Kerr adds: “Women have to command a better presence in terms of negotiating contracts.”

For its part, the AASA is providing female superintendents with mentors to help negotiate their salaries, Kerr says. The hope is that it will help balance out the gender-based salary discrepancy.

Outside of the gender wage gap, she says, superintendent salaries are “lagging.” (So, too, are teacher salaries.)

“Expectations have changed dramatically. We have taken on more responsibility—certainly we care for every child that walks through the door, but making sure their mental health needs are taken care of? We’ve become like therapeutic hospitals,” she says. “I’m not complaining—someone needs to do it. But making sure kids can learn means taking care of their social and emotional needs now.”

Education leaders have gotten creative in how they delegate those responsibilities—they’ve had to, Kerr says. Some are partnering with mental health providers, hospitals and other community organizations to tap into existing resources. It’s all part of the growing awareness of and emphasis on social-emotional learning.

The survey results were made public at the AASA annual conference in Los Angeles last week. During the event, Kerr says she noticed many new sessions focused on SEL and “how schools pivot and shift their focus for taking care of kids in a different way than some were used to doing in the past. It’s a very hot topic.”

The full results from the superintendent salary survey can be viewed here.