Artificial intelligence is well on its way to becoming a ubiquitous element in virtually all software systems. The once novel technology behind chess- and gameshow-playing computers is all but commonplace today; it’s in everything from medical diagnostic applications to Gmail spam filters—and as some high school and college students are finding out, a new generation of online tools for foreign language learning.

Ponddy Education, for example, is a San Jose, Calif.-based startup whose flagship products rely on AI technologies to help students learn one of the most difficult languages for non-native native speakers to master: Mandarin Chinese.

Strictly speaking, AI refers to a branch of computer science that focuses on machine intelligence (as opposed to natural or human intelligence). But as the term is popularly applied today, it refers to computer programming that allows machines to learn from experience, adjust to new data inputs and perform human-like tasks. (Think Amazon’s Echo smart speaker enabled by the AI software platform Alexa.)

Language learning is something of a sweet spot for AI, thanks to the capabilities of two core types of AI tech: machine learning and natural language processing. Machine learning algorithms support adaptive, personalized and spaced learning, while natural language processing technologies help with the extremely complex challenges associated with understanding and translating human language.

A growing number of vendors are offering AI-powered language-learning apps to companies and the general public (Speexx, Busuu, Duolingo) for hundreds of languages, but Ponddy’s products were developed specifically for secondary and university teachers of Mandarin.

“Mandarin Chinese is challenging on many levels for English speakers,” says H. Yalan King, director of business development and alliances at Ponddy Education. “The spoken language is tonal, which means one word can have four different meanings. The word ma can mean ‘scold,’ ‘rough,’ ‘mother,’ and ‘horse,’ depending on how you say it. And the written language includes thousands of special characters. Teachers and students need help and resources, which we are using AI technologies to provide.”

Launched in 2015, Ponddy Education makes AI-supported language-learning products and services. Last year, the company secured $6 million in its Series A funding round, and announced its plan to focus initially on Chinese “using the power of artificial intelligence” to “improve student’s success, while removing unnecessary costs and pain points for teachers and their schools.” The online Ponddy Advanced Placement Chinese Language and Culture course has also been approved by the College Board.

King, who also serves as executive director of the Mandarin Institute, acknowledges that her company took aim at a tough subject with its initial product offering. Written Mandarin features more than 3,000 characters and the language has been ranked by the Foreign Service Institute’s (FSI) School of Language Studies as a “Category IV” language, which means it would require 88 weeks and 2,200 class hours to reach “professional working proficiency.”

To put it another way, to gain the same proficiency level in Spanish would require 24 weeks, according to the FSI, whose website includes Mandarin on its list of “super-hard languages” for native English speakers, along with Arabic, Cantonese, Japanese and Korean.

Interactive Learning

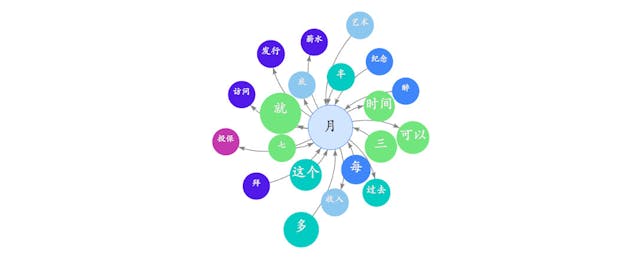

At the heart of Ponddy’s product line is its Affinity Knowledge Learning System (AKLS), an AI-based content curation engine designed to generate interactive learning modules. Interconnected with those modules are networks of relevant words, characters, and radicals (the basic graphical components of written Chinese characters.) In other words, the technology generates unique lesson plans based on teacher inputs, and helps students make sense of these concepts at levels that are right for them. The company describes the system as a “never before enabled language scaffolding” for personalized learning.

That scaffolding undergirds two AI-based products: The Ponddy Reader, which adds an online dictionary and sample sentences dynamically to any piece of content, and gives students quick access to visuals that group similar words, characters and radicals together; as well as the company’s Smart Textbooks, which automatically tailors learning to each student using the AKLS curation engine.

Those products also provide the technical backbone for a third element of the program, which employs live, online native speakers working with the Smart Textbooks and Reader.

Earlier this month, Ponddy launched “30 Days to AP,” a promotional program for students studying for the Advanced Placement Chinese Language and Culture test . The four-week intensive program includes four, two-hour sessions with a tutor, three hours of full-length practice exams administered by tutors (with personalized feedback) and a six-month Ponddy Reader subscription. (The test is scheduled for Monday, May 6, 2019, nationwide.)

Xin Chen has been teaching Mandarin at Berkeley High School in Berkeley, Calif., since she started the program 13 years ago. Currently several of her students studying for the AP Chinese exam are using the Ponddy software—21 of her 127 students (grades 9-12) are knuckling down for the test. Chen has been something of a beta tester of Ponddy’s tools; she and King are friends, and the company solicited input from Chen during the software’s development. “We got her opinion on early versions,” King says, “and she started using it in her classroom. Now it’s a resource for her students.”

Chen officially started using Ponddy Smart Textbooks in her classes last year, and recently introduced the Ponddy Reader. The Textbooks app uses AI tech to tailor learning to the level of each student’s abilities automatically. At a basic level, it translates complex writing into Chinese characters students are more familiar with. Teachers submit Chinese text, and the app transforms it into content with leveled vocabulary that aligns to world standards for Chinese language assessments, such as the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL).

She says the latter application has helped her implement a flipped classroom— where students move through units on their own and work on activities in class— by giving her a tool to organize authentic reading materials.

Chen uses the Reader to restructure contemporary newspaper and magazine articles into bite-sized “Pondlets,” highly visual interactive online learning modules. A curriculum is effectively a collection of Pondlets, which are focused on themes, such as dialogue, vocabulary, grammar, and cultural cues, at various levels of difficulty. Chen submits the materials she wants her students to study, and the AI-driven software aligns it for students and embeds the language scaffolding tools. Afterward, she can tweak the lesson to add things like comprehension questions and narration.

Those language scaffolding tools include a dictionary, which provides students with in-context definitions, pinyin (the system of writing Mandarin Chinese that uses the Latin alphabet), audio and sample sentences at various levels. As part of a lesson, a student might receive a conversation between two people written in Chinese characters with translations in pinyin and English.

“I think it’s cool that you are able to read these articles, and if there’s a character you don’t understand, you can click on a link and it takes you to an English definition,” says Leo Gordon, a senior at Berkeley High, who’s studying for the AP Chinese exam using the Ponddy tools. “I try to turn off the English translation and try to understand what the characters mean in context. It’s nice to have an opportunity to do that.”

Gordon is using traditional AP prep materials as well and says Ponddy holds up well by comparison. “The stuff on the actual exam isn’t going to be the hardest possible structure or sentence patterns,” he adds. “There’s definitely a lot of source material. But having articles that somebody studying can understand—I find that Ponddy has a similar ratio [in the reading material] of words I know and words I don’t know to some of the AP practice that we do.”

Ponddy is currently focused on Chinese, but plans to expand its tools to support other languages.

“Chinese is difficult and the field needs help and resources,” King says. “Plus, our founders are Asians and they saw the need, so we started there. But also, once we break the code, so to speak, on how to do this for Chinese, then it’ll be more easily adaptable to other languages.”

The company’s next target: English.