Imagine you’re in the market to buy a house. You’ve heard about various great neighborhoods from friends; at some point, you start dreaming about putting down roots, maybe even growing a family. You get an email or spot a description on the internet of a place that sounds sweet. One Saturday afternoon, you drive past it, catching a glimpse out the window.

Would you buy it without an inspection?

Would you buy it without knowing if it had a foundation?

For almost a decade, selling edtech products to schools and districts has felt dangerously like selling a home over the internet. We describe edtech products with all the excitement and adjectives of a fresh listing on Zillow. School buyers have some requirements but they’re also open to persuasion. They know the stakes are high: They’re making a commitment, not just to one season but potentially to years of usage.

But when it comes to demonstrating that products “work,” too many companies fall back on testimonials. Few can offer buyers independent assessments of the value of their products, even if those same entrepreneurs have sweated and toiled to build great wares.

The problem has been wrapped up in a tricky concept called “efficacy,” namely, the ability to produce an intended result. Efficacy is the quality of being effective. Everyone, whether an educator, an entrepreneur or a parent, should want edtech products that are effective—ones that genuinely help students learn. But unfortunately over the past decade or two, educational research has gotten tangled up in how the medical industry defines and measures efficacy—standards that are as inappropriate as evaluating a headache only with an MRI machine.

The resulting snarl has frustrated everyone: educators and parents don’t know how to evaluate edtech products; entrepreneurs don’t know what metrics authentically gauge their value. As researchers and investors, we have been vexed that products that we believe deliver great value to students struggle to demonstrate that value to potential new users.

Now the good news: Over the past year, we’ve seen a broader set of research practices applied to edtech. And these approaches can validate the power of emerging edtech tools in ways that authentically resonates with educators, entrepreneurs and others. It involves a continuous approach versus the one and done“gold standard” ideas that have proven more elusive than conclusive. And it asks that edtech company leaders think about efficacy in a proactive way from the very moment they conceive of their startup. It means building what we call an “efficacy portfolio” and it may be the single most important thing that any edtech entrepreneur can do to build a successful company.

Why the ‘Gold Standard’ Isn’t a Fit (in Edtech)

Why has efficacy been such a challenge in education? Way back in 2001, the Bush administration’s No Child Left Behind policy came down strongly in favor of “evidence-based teaching practices.” That approach was codified a year later when the U.S. Department of Education established the What Works Clearinghouse (WWC), which determined the definition and standards for measuring effectiveness. The WWC narrowed the scope of relevant efficacy data to two types of studies: quasi-experimental (QED) studies and randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

The medical industry has used RCTs very effectively for generations. Here’s a simplified version of how it works: Group A gets a placebo; Group B gets the experimental drug. Both patients and those administering the tests are “blind” to who is receiving which treatment. Researchers then study the outcomes.

But using RCT in education has turned out to be tricky. The conditions of a classroom are too different from those in a medical clinic. Learning environments, for instance, have a myriad of variables that are difficult to control. In an RCT, doctors control patient medical records, monitor health conditions and ensure that patients take the prescribed drugs. By contrast, teachers use interventions in multiple class sizes, with different levels of training and varying degrees of leadership support. Students are also not “prequalified”—in other words, they frequently begin a course of study with radically different levels of knowledge.

What’s more, parents rightly object if their students are not given every opportunity to succeed—and may protest if their child receives either an education “placebo” or an “untested” intervention. Finally, RCTs take literally years to complete and are costly. And while pharmaceutical companies can recoup those costs by debuting a high-priced final product, that approach will simply not work in education.

As a result, the What Works Clearinghouse’s definition of efficacy turned out to be so constraining that educators jokingly dubbed it the “Nothing Works Clearinghouse.” Entrepreneurs, moreover, couldn’t imagine waiting until their products were “done” to do a single, huge expensive RCT program. (After all, the best products are always shipping code and improving.) That left too many entrepreneurs throwing up their arms in despair or delaying plans to assess efficacy.

Fast forward 14 years to the Obama administration’s update of the NCLB legislation. Congress redefined its support of education under a program called the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) of 2015. As a part of ESSA, the government began to expand its “burden of proof” for resources adopted by schools. This included guidelines for curriculum and edtech. The Act outlines four tiers of evidence that schools and districts must see before they can use government funds for products and services. Those tiers are defined by the California Department of Education as follows:

Tier 1: Strong Evidence: [Edtech products are] supported by one or more well-designed and well-implemented randomized control experimental studies;

Tier 2: Moderate Evidence: [Outcomes are] supported by one or more well-designed and well-implemented quasi-experimental studies;

Tier 3: Promising Evidence: [Outcomes are] supported by one or more well-designed and well-implemented correlational studies (with statistical controls for selection bias);

Tier 4: Demonstrates a Rationale: Practices associated with [the edtech product] should have a well-defined logic model or theory of action, are supported by research, and have some effort underway by an SEA [state education agency], LEA [local education agency], or outside research organization to determine their effectiveness.

Tier 1 refers to RCTs but schools and districts can apply for government funding if a product can demonstrate that it has evidence consistent with Tiers 1, 2, or 3. And that means that instead of betting on a single expensive RCT carried out before a “final” product release, companies should start to develop a “portfolio” approach to demonstrating efficacy.

What Goes Into an Efficacy Portfolio?

An efficacy portfolio is a collection of evidence gathered over time that captures different elements of whether and how a product is “working.” Some of the evidence may include a QED or RCT—but those approaches no longer bear the full weight of demonstrating efficacy.

We see efficacy portfolios including three forms of research:

1. Summative Research

This is all about outcomes and includes the classic RCT and QED research programs. Evaluating outcomes in this way takes both time and financial resources. Summative research is most useful if it is carried out after a product exhibits signs of maturity and stability. Top-notch summative efficacy studies compare predefined groups and capture outcomes associated with specified conditions for product use.

These reports should include details about the nature of the institution using the product (i.e. Title 1, district, charter, private) and characteristics of the participants (i.e. age, grade, ELL, SPED, etc). Summative efficacy studies include correlational studies, quasi-experimental studies, and randomized control studies. These studies should be considered for well-established products, can take a year or more to complete and only need to be repeated every five years or so, depending on product changes.

2. Formative Research

Just as a teacher gives students coaching throughout the semester, formative research gives actionable feedback. It includes doing quick projects that have limited risk. It gives companies real-time information about how a product is working. It can include elements such as usability studies, feasibility studies, case studies, user interviews, implementation studies, pre-post or multi-measure research, and correlational studies. Every company should do formative research on its products throughout the life of the product to inform both the organization’s business strategy and product development.

3. Foundational Efficacy

This includes a host of projects that start with creating the guiding documents that outline the logic of a product. The product’s logic should be grounded in relevant research. These documents should also frame plans for demonstrating efficacy moving forward.

Foundational research frequently begins with a literature review and a logic model. The literature review should draw on the decades of learning sciences research about how distinct features (e.g. digital formative assessments) within a product have been shown to support learning outcomes—or not. Remember that technology for learning goes back decades, long before graphing calculators and smart boards. Much research has been done to understand how technology historically has and has not achieved the outcomes that many companies are working on now.

A logic model applies that research and creates a map that explains the product features, user activities, short-term outputs and long-term outcomes. A logic-model literally captures the DNA of a company. It helps internal stakeholders understand: What sets this company apart? What is the secret sauce? What combination of features makes the magic happen? And the ultimate question: Why are we confident this has value in the world?

In the nonprofit world, logic models are sometimes referred to as a “theory of change.” In academic research, they’re called “conceptual frameworks.” In edtech, the term “logic model” took hold because the U.S. government uses that term as a burden of proof for a company to meet the ESSA tier 4 criteria. Even so, foundational research is not static. Given how rapidly products evolve and new research emerges in learning science, foundational research must be refreshed at least every two years.

Organizations including WestEd and the NewSchools Venture Fund have already embraced the trajectory between formative and summative research. We recommend adding foundational research as a precursor to formative assessment and as a practice that continues through the lifespan of a product.

Think of foundational research as the base of a house, the structure that supports all else on top. From this perspective, then, formative research is like the structural testing conducted during the building process, the tests that examine the integrity of load-bearing walls and essential elements in the home. And because edtech products are being constantly updated, remodeled and improved, that process of summative assessment evaluation needs to be ongoing.

To help companies understand how they can begin the process of efficacy early and build their portfolio over time, we have created a list of efficacy projects and aligned them to the ESSA tiers. In this, we would also like to help consumers of edtech understand what types of data and research buyers might request to better understand the efficacy of a product.

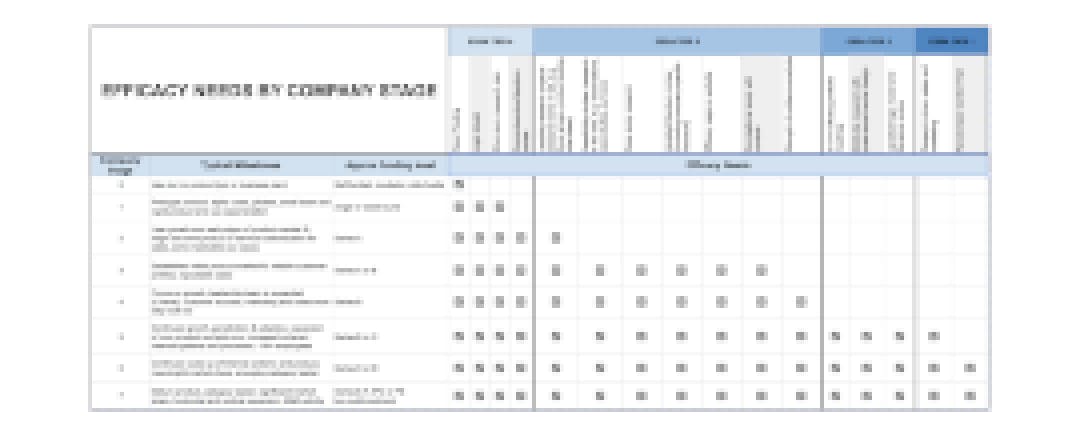

Efficacy Needs by Company Stage

Efficacy measurement ought to be a fundamental function of any startup. The concept is subtly woven into the principles of agile design: Efficacy measures help you know whether your product is doing what you set out to do. Testing early and often is the foundation of strong user-centered design. And because products are constantly growing, changing, and improving, a company’s understanding of its product’s efficacy should be updated as the product continues to develop.

But that doesn’t mean that a startup run by, say, two entrepreneurs should be undertaking an RCT. Quite the contrary: We believe that building a portfolio of efficacy means companies should undertake different projects depending on their level of maturity.

Just like people, edtech companies go through developmental stages. Those aren’t precise; just as children will learn to walk and talk at different ages, so too do companies hit milestones at different times. Even so, there should be a range of expected milestones for each organization. Based on an analysis of numerous edtech companies, we believe that edtech companies go through eight developmental stages. For each stage, MBZ Labs and Reach Capital have identified the typical growth milestones, approximate funding levels and efficacy expectations that we recommend for organizations at each stage. This chart is intended to provide companies insight into their stage of development and offer recommendations for gathering evidence at each given stage.

We’re not alone in underscoring the importance of efficacy portfolios. Investors are embracing efficacy to ensure their investments are executing on their positive missions. In fall 2018, firms such as Reach Capital, Emerson Collective, and NewSchools Venture Fund all made strides to strengthen the efficacy muscles of their portfolio companies.

In October, Reach Capital featured an efficacy talk at its Founder’s Day, highlighting strategies for impact work at various levels of growth. Later that month, the Emerson Collective hosted an event for its education companies focused exclusively on developing company roadmaps for efficacy. In November, NewSchools Venture Fund published an article aimed at increasing transparency about the cost of efficacy research, a subject that historically has been extremely opaque. NewSchools also supported its latest investment cohort by developing a literature review and logic model to help these companies build a strong efficacy foundation to carry them into the future.

It is never too early to begin building an efficacy portfolio. By thinking of efficacy as a portfolio of pieces, created at the right stage for a company, we hope that entrepreneurs will see that developing efficacy should be as fundamental to their work as raising money or ramping revenue. In fact, we’d argue that the best way to ramp and grow a company is to create a compelling portfolio of efficacy. Small investments in efficacy at crucial phases in a company’s development can reap large rewards that support continued growth and better their odds of maximum success and impact.