There are at least two truisms when it comes to education technology:

1. Teachers don’t always use what their district purchase. And 2: Many scour the web to find tools to use on their own—often without the knowledge or approval of school leaders.

That gung-ho initiative is something that Mark Racine, director of technology at Boston Public Schools, applauds. But it also gives him pause. When teachers choose their own tech, “they can disrupt security practices, and there’s no visibility at the district level into what’s being used. When there is a problem, we find out about it too late.”

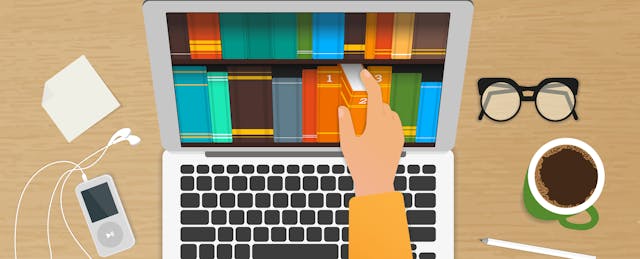

To continue encouraging teachers to find tools while still keeping tabs on what they’re using, Racine has asked them to turn to another destination: the Clever Library. Soft-launched last summer, the library currently houses more than 100 educational apps, which teachers can browse by subjects or categories (like assessment or presentation tools). And with one click, teachers can also conveniently make those resources available to students.

Provisioning apps quickly and securely has been core to Clever’s business since it was founded in 2012. The San Francisco-based company is best known for its rostering technology that provisions user accounts for software, and a single sign-on service that makes it easy for students and teachers to log into and use tools purchased by district officials.

With the Clever Library, the company aims to give teachers more agency in finding and trying new products. Often, the most popular apps “are what teachers are discovering at conferences, reading online, and across social media,” according to Dan Carroll, chief product officer of Clever. The goal is to “support teachers in finding new tools, while also making them as easy and safe to use as possible.”

The disconnect between what school leaders buy and what teachers actually use is well-documented. A report published in January suggests that most software licenses purchased go unused. Meanwhile, the number of tools in classrooms today has ballooned. Another recent survey found that, on average, districts saw more than 700 different edtech products used each month during the last school year. (Suffice to say, school leaders are not keeping tabs on all of them.)

So far, the library has since been accessed by around 250,000 teachers, who have made more than 9 million student accounts for the apps, according to the company.

This latest effort builds on an earlier attempt by Clever to help districts test new tools. In early 2016, it launched Co-Pilot to give schools free 30-day trials of edtech software built by other companies. But “the time period was too short, and these district-initiated pilots often struggled to get teacher engagement,” says Carroll. That effort wound down by the end of that year.

“While Co-Pilot wasn’t the right solution, our work on it confirmed our belief that it’s way too hard for educators to discover and select high-quality software, so we began work on the project that became the Library shortly after sunsetting Co-Pilot,” he explains.

Inside the Library

The Library is not yet open to everyone; only teachers in districts that have integrated with Clever can access it. So far, that includes educators in more than 60,000 U.S. schools.

Upon logging in to the Clever Library, teachers can see a list of the most popular web apps used in their district. Each app has a profile that includes a brief description of the product, pricing information and what technology platforms and devices it can be used on. Teachers can also see how many of their peers in the same district have tried it, along with their comments and reviews about the tool.

When teachers finds something of interest, they can click a button to create student accounts for the class. All that is required for each account is a student’s first name, last initial and grade level; no other personal information is required. To access the app, students simply navigate to the class’s Clever page.

Perhaps most importantly for district tech officials like Racine, each profile also includes links to the developer’s terms of service and privacy practices. There is also a link to Clever’s data-sharing agreement, a set of security and privacy rules that the company co-developed with education-privacy lawyers, and which every third-party company that works with Clever has agreed to follow.

“The teacher’s primary role is student learning, but student privacy isn’t always at the top of their mind,” says Racine. When teachers use tools they find online, they can inadvertently run afoul of privacy and security guidelines. Third-party software can share student data in ways that violate district or state standards. And they may be vulnerable to hackers.

“It is absolutely critical for me to know that all student information is secure,” Racine states.

School and district officials can see which apps have been installed, and how frequently they are used. They can also recommend or restrict which ones are available for teachers to try. For instance, a curriculum director may decide that one math program does not align with the district’s academic standards, while another one does. Or sometimes, an IT director may not be comfortable with an app’s privacy policy and restrict teachers from using it.

For Clare Trumble, who teaches 7th- and 8th-grade English at the Metropolitan School District of Wayne Township, in Indianapolis, the library has “saved a lot of time when I’m trying to find things that are of interest to kids, that they can use safely.” She often browses the collection at home, and if she finds something she likes, she can have students use it the next day. She estimates that she has already tried 20 different apps with her class since last summer.

Marketplace Mania

Creating a one-stop shop where educators can browse, try and buy online resources has so far been a pipe dream for the edtech industry, where many companies have tried building pieces of this vision. Success has proven elusive. Startups have ran out of money. Attempts from the likes of Amazon and publisher Houghton Mifflin Harcourt have sputtered. Other efforts, such as Common Sense’s Graphite, have required substantial support from philanthropic funders.

Last week, Google became the latest to toss its hat in the ring with the launch of an App Hub where educators can find online resources and apps to use on Chromebook devices. Like the Clever Library, the hub offers detailed profiles of educational tools that include basic descriptions and privacy policies.

While the Clever Library has the makings of a new distribution channel for education software, it is not a fully open marketplace. There is no way for educators to directly buy materials. Each app in the library is available either for free or freemium (meaning a limited set of features are free).

That might change. Racine says that Boston Public Schools has been “cautiously testing” a new feature that allows teachers to make direct purchases. Already, one teacher has paid out of pocket for a software license, which has raised concerns among administrators. In many districts, allowing teachers to make direct software purchases would require changes to established rules for procurement and reimbursements. There are no plans yet to roll out this functionality.

For companies, the Clever Library offers an opportunity to get more users to try their wares. If enough students and teachers like and use a product, that can make a strong case for the school or district to purchase a school-wide license.

Companies can track their app’s usage activity through the library, which can inform their sales efforts. For Edulastic, an online assessment provider, being on the platform helped close deals. “If we see a lot of teachers use our product, that’s a sign of a warm lead, and we can reach out to the district” to upsell them on a site license, says co-founder Aditya Agarkar.

That benefits Clever as well. The company charges developers a fee based on the number of districts that have paid for site licenses to use their tools, and which use Clever for rostering and single sign-on services. So as more districts purchase licenses, Clever can charge the developer higher fees. “It feeds into the traditional business model” of the company, says Carroll.

The ability to quickly deploy apps for students remains, for now, a distinguishing feature of the Clever Library. That could entice more districts and companies to integrate with the company’s offerings, which is key to staying competitive with potential competitors like Google, which have much deeper financial pockets.

Clever has raised more than $43 million in venture funding. Carroll did not comment on its profitability other than saying “our revenues are growing quickly.”