What if you could map every book and article assigned in college courses around the world and see which authors are making the most impact?

A project run out of Columbia University is working to do just that. It’s called the Open Syllabus Project, and this week its leaders released a new version of their tool that analyzes assignment lists from more than six million syllabi.

While the collection doesn’t represent a complete picture of higher education (the U.S. is heavily overrepresented, for instance), it is the most comprehensive dataset of its kind ever assembled. Scholars can look for trends in which ideas cross disciplines, how ideas in fields change over time, and more.

“This is a representation of the complete enterprise of higher education,” says Joe Karaganis, project director of the Open Syllabus Project and vice president of a public policy institute at Columbia University.

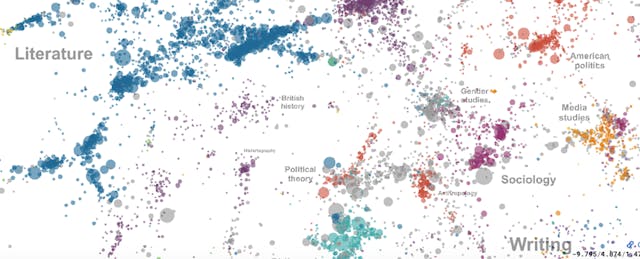

A previous version of the project was released in 2016 with about one million syllabi. But version 2.0, released this week, is not only larger, but also allows users to view an interactive visualization that shows almost every text as dots on an interconnected map of knowledge. The larger the dot on the map, the more often it is assigned in a course. “You can see the ways in which fields connect, and the way subfields emerge out of established fields,” says Karaganis.

Version 2.0 also makes an attempt to assign a score of 1 to 100 to each text that measures its influence in classrooms.

“We think of this as a new publication metric,” says Karaganis. He notes that typically scholars look to citation indexes to see how frequently their work is mentioned in other scholarly works, but there hasn’t been an equivalent for how often texts are taught. “We can now let faculty take credit for the work they’ve produced that has teaching applications,” he added.

Most-Taught Texts

The most assigned author in the collection is William Shakespeare, who appears nearly 50,000 times among the 1.4 million authors assigned in the syllabi. Second place goes to Plato with more than 27,000 mentions. In third is Diana Hacker, an author of books on how to write, whose works appear on more than 25,500 syllabi. (She’s apparently more influential than Aristotle, but not by much.)

The earlier version of the collection drew controversy when Karl Marx turned out to be the third most popular author in the first million syllabi collected (he now ranks sixth). That was flagged by some right-wing commentators as evidence of liberal bias in the academy. Karaganis, though, notes that the Communist Manifesto is most often taught in history courses.

Jon Becker, associate professor of educational leadership at Virginia Commonwealth University, says he thinks the expanded dataset could become a meaningful resource. But he also expressed concern that the presence of a score for how often texts are assigned may end up having unintended side effects.

One problem is that the system may lead to less diversity in classroom assignments as people look to the dataset for guidance. “Maybe some more marginalized texts get even more lost because a department decides not to adopt it because it doesn’t have as high a score,” he says.

Becker also notes that the tool may wind up with gaps because some professors are reluctant to share their syllabi publically. The Open Syllabus Project scans college websites, but can only see what is on publicly shared sites or is submitted directly to the collection.

Why are professors hesitant to share their syllabi? “My guess is that folks are worried that it will get critiqued in ways that they’re not comfortable,” Becker says. “Some professors aren’t as confident in their teaching as they are in their research.”

The public website of the Open Syllabus Project does not give access to individual syllabi and does not say what professors are teaching which texts. Instead, it lets users search aggregate information drawn from the collection.

Karaganis says the project hopes to allow scholars who request access to download a more complete version of the dataset to do their own number crunching, though the database will not be used for commercial purposes.

Over time, the project’s leaders also hope to let users search on more details within syllabi. One field coming soon will be the gender of the authors of assigned texts. “What that will enable us to do is look at the history of gender balance in teaching and how it’s changed over time and how it’s looked in different disciplines and departments,” says Karaganis.

Anecdotally it’s clear that what professors assign today is far different than 50 or 100 years ago. At some point, tools like the Open Syllabus Project may make it possible to track those changes in a more concrete way.