The following is the latest installment of the Toward Better Teaching advice column. You can pose a question for a future column here.

Dear Bonni,

You have shared often about active learning strategies and the impact they have on student learning. However, I am dubious that the approaches you describe work with large classes. What about when you have 50-60 students in a class? Or even hundreds?

—Anonymous

In my experience, it’s true that small classes provide greater opportunities for student engagement and for professor/mentor relationships to occur. However, there are certainly those who employ methods that put this perspective to the test.

As I’ve been thinking about this issue, I keep coming back to two key questions:

What can we discover about the relationship between class size and student learning?

When we teach large classes, what approaches can we employ that will have a greater opportunity to engage students and help students learn more?

A study was published by IDEA, a non-profit organization that focuses on academic success in a higher education context, which explored whether class size is a factor in perceived learning. The authors—Stephen L. Benton, Dan Li and William H. Pallett—analyzed data from 490,333 classes that were tracked by the IDEA Student Ratings of Instruction systems. Over 400 different colleges and universities were included in the research.

That study concluded that there isn’t a significant relationship between the size of the class and how well the students did in demonstrating learning outcomes. It’s worth noting, though, that the courses that were large tended to emphasize knowledge-based material. In online courses, the size of the class matters less than the reasons that students cite for enrolling.

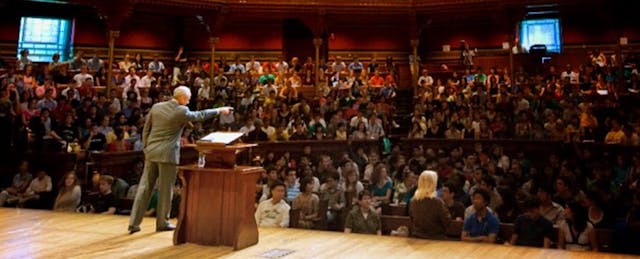

Some large classes can create a shared experience for students that will be a class that they don’t easily forget. Michael Sandel, a professor of political philosophy at Harvard, teaches one of that university’s most popular courses: Justice. It became so popular that Harvard now offers it as a free version of it on the edX platform. He is a master at the Socratic method of asking questions that get even the most passive of learners thinking. When my students watch his videos, they say they feel like they are sitting in the same Harvard classroom that is being filmed and are participating in the dialog with the other students. If you would like to see Sandel in action, the Justice videos are viewable on YouTube, without needing to enroll in the course.

Some approaches I observe Sandel using are:

- Asking open-ended questions and having all students silently reflect on their answers before anyone shares to the broader class.

- Inviting students to predict what will happen next in a story, or what they think will be the result if a specific choice is made.

- Using minimalist slide decks, and therefore not overwhelming students with lots of text to digest while he is speaking.

- Starting each class session by asking students to recall what was discussed in the previous session.

- Calling students by name, even in such a large class. He asks each student who speaks to identify themselves, and he regularly refers back to that speaker much later in the same class session.

- Painting pictures in the students’ heads through excellent storytelling.

- Exploring many different applications of the same concept. For example, what does libertarianism look like in historical events, in bioethics, in compensation, and in human rights?

Another master teacher of large classes is Michael Wesch. He is a professor of cultural anthropology at Kansas State University whose expertise as a digital storyteller has won him widespread attention for his videos, which have been translated into more than 20 languages, viewed by more than 20 million people and featured at conferences and film festivals around the world.

One of his large class projects is ANTH 101. The course is designed around ten different challenges that students wrestle with during the semester. And all students, even ones not formally enrolled but who find the free course materials online, are encouraged to share their learning with others. His teaching assistants have engaged with students in the class from places such as Ethiopia, Northern Ireland, Guatemala, Samoa and Vietnam. Rather than emphasizing the memorization of a set of definitions in the discipline of anthropology, Wesch invites us to “a new way of seeing the world that can be valuable regardless of your career path.”

He challenges us to see how the structure of his course helps us to put on these new lenses. He suggests a simple truth about learning:

“You can’t just think your way into a new way of living. You have to live your way into a new way of thinking.”

Some approaches I observe Wesch using in ANTH 101 are:

- Centering the class around 10 big ideas and linking the assignments around those same ideas.

- Referring to assignments not as traditional homework, but as “challenges,” and making sure that each one represents something that will be relevant to the students’ lives, both now and in the future.

- Encouraging students to share their learning in a radically public way. Both students who are formally enrolled in the course and those joining in because they want to are asked to share their responses to the challenges on instagram, on blog posts, and on Twitter using the #anth101 hashtag. These answers are curated on the main ANTH 101 website.

- Extending the learning from ANTH 101 out to other institutions. He offers a free set of resources for instructors who wish to use the ANTH 101 materials.

- Telling innovative digital stories through his extensive collection of videos. What he does is not technically difficult (in terms of video editing), but he has done lots of iteration and thinking differently about how to keep viewers engaged.

Way back on episode 25 of the Teaching in Higher Ed podcast, I talked to another expert at engaging large groups of students: Chrissy Spencer, who teaches at Georgia Tech. One of her big lessons is to invite her students to become active participants—in one example she invites them to play the part of a chili pepper population in a simulation designed to teach evolutionary processes.

The big challenge of large classes is keeping students engaged. But such engagement is not just an issue in big classes. Quality Matters suggests we need to consider more ways to get our students active in their learning, and to focus on the issue no matter the class size.

For Spencer, one key strategy is having students do focused group work and reinforcing their learning through means other than strictly relying on passive listening to lectures.

Some approaches I observe Spencer using in her large classes are:

- Actually having students in the class embody parts of the concepts she is trying to teach.

- Employing prediction as a means of deepening learning through a series of interrupted case studies. These structured experiences allow Spencer to identify when students misunderstand concepts early on, before they have gone too far into the case without receiving feedback.

- Offering team-based, low-stakes assignments to get students explaining what they are learning to others in the class.

- Including service learning as part of course assignments, so that students can experience how what they are learning can help the local community in some way.

- Bringing something she loves (like chili peppers) into the classroom and helping that passion spread over to the students.

- Using tools like the CATME Team Maker to carefully construct teams that consider everything from demographics, preferences and even whether or not a student has transportation to participate in the service learning opportunities into the mix of how groups get created.

I am among those who treasure what can happen in small classes. However, when I am exposed to people who are masters at engaging students in large classes and helping them succeed academically, I am reminded that class size is not as important as I might sometimes find myself thinking that it is.