WASHINGTON, D.C. — Jerard Briscoe is away at school. Or at least, that’s what he tells his kids.

It’s a plausible story. He studies for GED math exams. He reads e-books and takes courses using a tablet computer. He even wears a uniform: an orange jumpsuit and white Velcro sneakers.

“If you’re at college, you can’t go home everyday anyway. I just put my mindset like I’m really at school,” he says. “So when I tell my kids that, I’m lying a little bit, but I’m not really lying, because I am at school.”

He thinks for a beat.

“Alternative school.”

That idea is spreading through the corridors at the D.C. Central Detention Facility, slipping past security checkpoints and into cells where incarcerated residents watch Khan Academy videos and craft their resumes. It’s a big shift from just a few years ago, when inmates say they passed long days with little to do but play cards and pick fights.

That was before Amy Lopez showed up. In 2017, the petite Texan arrived at the jail with an armada of plans and the energy to launch them. She invited college professors to teach for-credit classes inside, in person. She purchased tablets to offer short-term learning opportunities to transient inmates. And she created a residential learning bloc named for the phoenix, the mythical bird that rises from its ashes to have a second chance at life.

“Every single person I talk to—staff members or incarcerated students—will say it was a game-changer when she arrived,” says Marc M. Howard, director of the Prisons and Justice Initiative at Georgetown University. “I’ve never seen an administration, a staff, an agency so supportive of programming for its incarcerated residents. I think they’re a model of what corrections officials around the country should be.”

To Lopez, a former public school teacher, the radical changes make perfect sense. Her facility houses 1,800 people a day who have gaps in their schooling and who may one day be back out in the world.

As Lopez easily navigates the maze of cinder block hallways and hollers code numbers to an unseen elevator operator, she muses aloud in her Lone Star drawl: “What if you treated everyone as if this were an academic campus?”

From Public School to the Prison System

Lopez is now working toward a doctorate in developmental education, but as an undergrad, she majored in theater. That stage training is surprisingly relevant, she says: “I use it every day.”

She taught drama, English, reading, art and speech in Texas public schools before moving into administration as an assistant principal, and later a principal. Seeking something new, she switched to prison education, becoming principal at a juvenile detention center that sometimes housed boys as young as 10.

She didn’t get much training before making the shift.

“That probably made me incredibly good at my job,” she says. “Because I didn’t know any better, I ran it like a regular school. We had positive interventions and supports. ... Everything improved. Serious incidents went down to nothing.”

Her subsequent work with incarcerated kids and adults didn’t go unnoticed. When the Obama administration sought to reduce recidivism by building a school district within the federal prison system, Lopez got a call.

U.S. Deputy Attorney General Sally Yates asked her to leave Texas for D.C. to become the first superintendent of a new Bureau of Prisons school district. The plan was to create personalized education plans for each inmate. A pilot program would test the use of tablets in combining online education with classroom teaching in a prison setting.

Lopez’s new gig, chief education administrator for the federal BOP, was announced in November 2016.

“I was the only one of those they ever had,” she says, ruefully. “The hot minute that I was there.”

After Donald Trump began his presidency, Lopez lasted five months.

“It’s terrible to be famous for being fired,” Lopez says. “I went out with Sally Yates; I’d go out with Sally Yates any day of the week.”

She wasn’t unemployed for long. D.C. Department of Corrections Director Quincy Booth, himself a former teacher, scooped her up. Together, they crafted her a new position: deputy director of college and career readiness and professional development. If the inmates across the whole federal system couldn’t benefit from her ideas, at least those in the nation’s capital might.

It didn’t take long for guards and administrators to notice the effects her programs were having on inmates, who Lopez calls residents.

“It’s awakening the giant in them,” says correctional officer Temesghen Andemichael. “Education is the key to changing their circumstances, they believe in that.”

Testing Tablets

It turns out, people in jail love TED Talks.

The videos are inspiring, informative and—perhaps most importantly—available any time on the tablets they can borrow for hours on end.

It’s loud on the Phoenix Unit, the special learning wing where these residents live and test educational pilot programs. Large fans whirr constantly overhead. Two floors of numbered cells surround open hallways just wide enough for a row of picnic tables. Spanish-speakers cluster around one, studying English. At another, a man tackles math problems with a calculator.

The tablet computers allow inmates to drown out the din. They slip on specially designed headphones and immerse themselves in recorded lectures and digital texts, with the occasional break to listen to music from preapproved radio stations.

“It kind of takes you away from this place sometimes,” Briscoe says.

Putting this type of tech tool in a prison or jail can be a hard sell to corrections officials, though.

“They think something bad is going to happen,” Lopez says. “It takes time to build enough relationship capacity to know I wasn’t going to do something crazy.”

But within her first few months at the D.C. jail, she got support to bring in the tablets. At first, the computers primarily offered online college courses from Ashland University.

“I went through and found people who already had a high school diploma or GED to fill out their FAFSAs,” Lopez says, referring to the federal forms to apply for financial aid. “I didn’t have a team at the time. I went from cell to cell recruiting, did all the paperwork.”

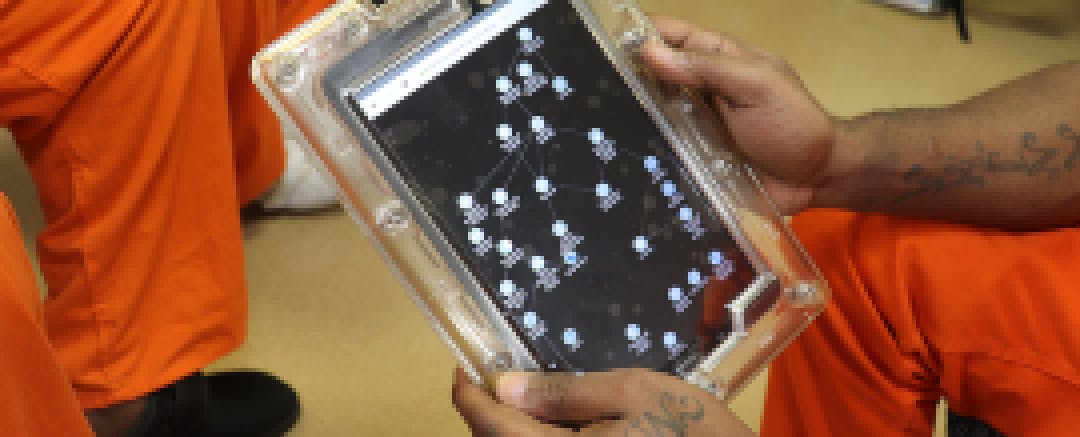

Then, Lopez got more programing for the tablets from American Prison Data Systems, a for-profit company that charges facilities, not inmates or their families, for the tools. The Samsung devices are wrapped in thick cases and loaded with education software selected to serve residents’ needs.

The computers can’t access the internet, per jail rules, but they’ve got videos and a library of books that inmates can read without having to wait weeks for their families to send them Amazon paperbacks. Favorites, residents say, include self-help books, stories about overcoming hardship and works by Malcolm Gladwell.

The tablets also come with courses that residents can take to pursue their own educational goals at their own speed. As a group, incarcerated people have less education than people on the outside, but their levels of degree attainment vary.

That makes a corrections facility like a one-room schoolhouse full of students who have different needs. With the tablets, ESL students can take classes from a company called Voxy to learn practical English at the same time that their unit mates take online college courses from Ashland.

Among the most popular tablet programs here are entrepreneurship and career readiness classes, and residents muse about their business plans for food trucks and construction companies and nonprofits designed to help fellow former prisoners.

Incarcerated people like entrepreneurial education in part because they know it’s hard to find work with a criminal record, says Chris Wilson, director of engagement for APDS and author of “The Master Plan: My Journey from Life in Prison to a Life of Purpose.”

“We have this stigma of being convicted of a crime,” he says. “Everyone wants to be their own boss.”

Residents have gotten creative with the tools. Russell Gaskins, known throughout the jail as Rock, has been learning Spanish from his five-year-old daughter. He wanted to teach her something in return.

“She has a tablet. So what we’ve been doing is downloading the same books. And we’ve been teaching each other, having conversations about the books; she’s learning how to read,” Gaskins says. “Having the tablet, having the same books, we can look at the same pictures. I’m still intimate in her life without being there.”

Teaching Through Transience

In a prison, inmates can struggle to find enough stimuli to fill their days—and years. In a jail, the challenge is to snatch fleeting chances to meaningfully change their lives.

At the D.C. jail, some residents are there to serve short misdemeanor sentences. Others are awaiting trial for more serious charges. Still others have been sentenced and may be transferred at any time to a Federal Bureau of Prisons facility hundreds of miles away. Lengths of stay range from less than a week to several years.

“It’s a limbo land, and unfortunately it’s a limbo land they’re really thriving in,” Lopez says. “There are days we go to hand out a tablet and they’ve been picked up in the middle of the night by U.S. marshals and taken off. We don’t have any warning. They’re sometimes pleading with a lawyer to ask a judge, ‘Can I stay for the end of a semester?’”

This disruption can be detrimental to earning credentials. Yet some residents say their time in jail is the first occasion they’ve had to really focus on schoolwork. Inside, they don’t have to worry about the gun violence, hunger and hustling that marked their lives on the outside.

“Even if you don’t finish and you happen to be getting transferred, say to the BOP, your mind is still on what you were trying to accomplish here, too. So this really, really do help us,” says James Johnson, a Phoenix Unit resident. “Even if I get transferred today or tomorrow, my mindset is going to be on trying to find something else to do, positive, some type of educational program. Because you ain’t going to get this everywhere.”

Lopez advises inmates who are transferring to prison elsewhere to immediately ask in their new facility, “What’s available to me?”

Despite the transience in their jail, Lopez and Booth have complemented the tablet program with traditional, for-credit college courses taught in person by Georgetown professors. Faculty bring in Georgetown students who live on campus to study alongside their incarcerated classmates. At the D.C. jail, the university offers the country’s first co-ed class for people in the system.

The welcome Howard has experienced in the facility in D.C.’s southeast corner contrasts sharply with the attitude his colleagues encounter in other parts of the country, where there’s a sense, he says, that incarcerated residents are “simply to be warehoused, held in cages, and they’re not deserving of any opportunities.”

“We feel very much wanted, partners on the same team,” he says. “That’s very unusual.”

Howard has lost students mid-semester. This week, one of the few women in the Georgetown program was sentenced to what will likely be five years in federal prison. Almost simultaneously, another student was released unexpectedly.

“We had testified on his behalf at his sentencing hearing. The judge said what he was doing in our program was so good, he would support his release,” Howard says. “On Monday, I testified. He was released 15 minutes later. On Tuesday, he was in our Georgetown class” on campus.

Among the Georgetown inmate-students is Joel Castón. He’s been in the D.C. jail for three years, waiting for a judge to revisit the life sentence he received as a teenager, when he was convicted of murder (a verdict he has appealed). He’s written a book about investing and personal finance, and he studies Mandarin in his free time. Lopez jokes that she assumes she’ll be working for him some day.

Castón uses a tablet to study other topics, like business soft skills. He’s been in the system so long that the tool has offered him otherwise rare encounters with modern technology.

“The tablet has become my companion,” he says. “Just think about the leisure of not spending idle time inside a room—you can utilize that time to actually study something of substance. That’s fabulous. Now you can actually maximize this experience.”

Measuring Change

On weekends, with her pet greyhound in the back seat, Lopez drives her blue coupe all over the D.C. area, to battlefields and museums and even way up north to see Niagara Falls.

She savors the liberty to learn that she hopes the jail’s tablets offer residents, albeit on a small scale. The freedom to read a book when they choose. To move forward in a class at their own pace.

Riding in that car on the way to a correctional officers meeting, Lopez mentions she’s never been the victim of a crime. Still, she can’t help but wonder how much punishment is enough to atone for the acts that incarcerated people are convicted of committing.

“What does more time do?” she asks.

In the long term, Lopez wants to change Americans’ attitudes toward students like hers, mostly men of color whom she views primarily as “really enthusiastic adult learners.”

“I don’t look up their offenses,” she says. “It doesn’t matter to me.”

More concretely, Lopez wants to figure out how effective her programs are, analyzing, for example, whether blended learning is more helpful than tablet-based study alone. And she wants to set clearer benchmarks for each student. She hopes to change their trajectories after they’re released, making sure the schoolwork they do in jail ultimately helps them get better jobs that pay living wages.

A watershed RAND evaluation of correctional education programs published in 2013 found that inmates who participate in such programs have 43 percent lower odds of recidivating than those who don’t. Yet it may be difficult to measure recidivism among Lopez’s students, who can be sent all over the country to carry out their sentences.

Even so, she and her colleagues are working to prove the program’s worth. The tablet system allows jail educators to track the progress that individual inmates are making in their skills and classes. APDS is collecting data from multiple facilities where its tablets are used to assess what’s working. In one jurisdiction, the company’s program helped increase GED pass rates by 57 percent, says Arti Finn, APDS co-founder.

Anecdotal evidence looks promising so far.

“We were not even a month into our pilot program when Director Booth and I had a meeting, and he told me there’s been a culture shift already. He’d never seen it before,” says Howard, the Georgetown professor. “He would hear people discussing what they’d learned in class, debating philosophy. He overheard a phone call where someone said, ‘Mom, can you believe I’m in a Georgetown class?’ with such pride.”

In addition to the hopes Lopez has for her students, they have goals of their own. Briscoe wants to earn his GED, study information technology through Ashland University and help his three daughters and two sons with their homework.

But he doesn’t think only of himself. He advocates on behalf of his peers who have less access to resources than he has on the Phoenix Unit. It would reduce rates of violence, he says, if more residents had more opportunities to study.

He also thinks it would prepare them not only to reenter the outside world, but to succeed there.

“A lot of people come to jail and just leave with nothing. They don’t know nothing but what they knew before they came,” he says. “If you had something to go out there and look forward to, there’s less chance you’ll be turned back.”