Government spending on higher education has shifted significantly over the past two decades, with federal support increasing and state support decreasing, according to a new report from Pew Charitable Trusts.

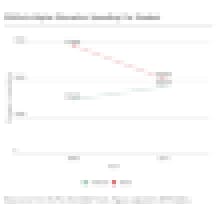

Between 2000 and 2015, federal dollars going to colleges per full-time student increased 24 percent, to $4,544, while state spending fell 31 percent, to $5,099 (adjusted to 2017 dollars).

With a third of revenue at public colleges coming from governments, these shifts matter because federal and state budgets set different priorities for spending tax dollars. Federal higher education funds primarily target research projects and individual students through financial aid, while state money mostly supports the general operating costs of public institutions and local dollars typically go to community college systems.

For students, the result may have been a higher sticker price. Some economists blame falling state support for rising tuition, while others instead blame increased institutional spending on amenities and administrators.

The report reveals disparate government reactions to the Great Recession, says Rebecca Thiess, associate manager for The Pew Charitable Trusts’ fiscal federalism initiative.

“Federal spending increased as more people were going back to school and applying for those benefits. At the state level, states were tightening their belts,” she says. “One of our takeaways about higher education funding is that the federal government and the states really don’t coordinate their approaches.”

Here’s a look at how government higher ed spending strategies have changed.

In the past 20 years, increases in federal spending stemmed partly from policy changes, such as the Post-9/11 GI Bill, which extended education benefits to a new generation of military members and veterans. Between 2007 and 2017, federal spending on veterans’ higher education benefits grew nearly 250 percent, in inflation-adjusted terms, according to the report. These benefits mostly went to private nonprofit and for-profit institutions, with a third going to public schools.

The uptick in federal spending also came from increased demand for financial aid during the recession. Pell spending increased by $18.3 billion (96 percent) between 2008 and 2010. More than two-thirds went to public colleges.

“More people were choosing to get an education with job prospects declining,” Thiess says. “It shows how federal funding really does follow students and what student needs are during different economic cycles.”

Public colleges receive varying levels of state support depending on policy decisions such as how high tuition rates may be, Thiess says. By 2018, only nine states hit pre-recession higher education spending levels, according to a report from the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association, while in another 11 states, funding remained below the low point of the recession.

But public colleges also receive different levels of federal support, too. That reflects, in part, each state’s unique level of student financial need and number of veteran students, plus disparate federal investment in academic research projects.