Across the country—and indeed the world—schools are preparing for a back-to-school season unlike any other in living memory.

Governors are signaling tentative support for schools to resume in-person classes in the fall, with careful planning and a few caveats. Colorado’s governor, Jared Polis, went so far as to describe his vision as a “hybrid environment,” allotting for altered schedules and intermittent returns to remote learning based on the predicted trajectory of COVID-19 over the coming months.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, a key member of the White House coronavirus task force, has warned of serious consequences if schools open too soon. Other workplace and public health experts say reopening plans like those proposed by Gov. Polis are realistic but that there is a lot of work to be done. “There’s going to be some real challenges here,” says Dr. Georges Benjamin, the executive director of the American Public Health Association, in an interview. “The intent is to put in place protections the best you can.”

Already, schools in Europe have been moving students back into classrooms, experimenting with half-sized classes, one-way hallways and open windows to increase airflow circulation. Earlier this month, an infectious disease specialist in Germany told the New York Times that reopened schools causing a second outbreak was his “biggest fear.”

Such concerns are not unfounded. In France, about 70 virus cases have been linked to schools, though most likely became infected before the reopenings. Germany, which is slowly getting students back to class, has already had to close a handful of schools.

It’s fair to assume that we can expect the same in the United States. “In the short term, are we going to be able to eliminate all infections? Absolutely not,” says Dr. Benjamin. “There will be outbreaks that will happen in schools and they will have to do all the usual things around contact tracing and deciding whether class is dismissed for that day, or whether or not it impacts the whole school.”

But Dr. Benjamin and others believe that as long as basic precautions are taken, the risks can be minimized—and thus worth the tradeoffs of getting kids back into class. Social distancing, at-home and in-school temperature checks, frequent hand washing, and smaller class sizes will likely help slow infection spread, though schools may need to close again as outbreaks develop.

“Unfortunately, until we get a vaccine, we’re having to make a lot of tradeoffs that we wouldn't normally make,” says Dr. Benjamin.

As a general rule, experts advise keeping schools closed until virus cases in a given region are manageable, meaning timetables could look different from one district to the next.

“Pulling the trigger on reopening schools is predicated on cases declining over a period of at least two weeks in each area,” says Dr. Dean Winslow, an infectious disease specialist at Stanford University Medical Center in California. “I would even, as a very cautious person, say it should be a few more weeks than that to see objective declines, and then you [reopen] district by district, or county by county.”

The best way for schools to make those decisions is in concert with local health departments, which can also help advise on mitigation strategies, he adds.

The New School

Enforcing the strict social distancing and hygiene measures necessary to prevent an outbreak is no small undertaking. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has released limited guidance that leaves much of the decision making up to state and local education authorities.

Already states are putting together back-to-school plans focusing on scheduling and other practical concerns. Some go into details around mask-wearing etiquette, temperature screenings and cleaning procedures.

Schools will also need to wade through a morass of individual concerns around cafeteria and classroom seating, transportation and, in some cases, retrofitting bathrooms and other facilities, says Nellie Brown, the director of workplace health and safety programs at the Worker Institute at Cornell University.

Toilets, for example, will need lids to prevent particles from becoming airborne when flushed. Hand dryers should be replaced with paper towels. “I hate to say that we have to do some of these things, but we can’t afford to move airborne particles around or make anything that’s begun to settle on the surface become airborne once again,” says Brown.

“It will be disruptive,” she adds. “I don’t see any way around it.”

Reducing airborne spread, along with frequent hand washing, are among the most important mitigation strategies for schools, says Dr. Winslow.

“The obsession with cleaning every surface is important, but the transmission by fomites is much less important” than in-person transmission, he says, using a term for objects that can transfer diseases, like door handles. “I personally don't recommend going crazy and using harsh chemicals, particularly on surfaces that can be damaged. The most important thing is to encourage very frequent hand washing. That’s probably more important than just cleaning environmental surfaces.”

For older children, and those who are able to wear them, masks may also be useful—though how much is difficult to say.

“It’s really hard to sort out when you put in a whole bunch of interventions,” says Dr. Winslow. “As you probably know from studying science, it’s not exactly a controlled experiment. My own prejudice is it’s probably a small but incremental part of reducing spread.”

Social distancing will also need to be rigorously enforced, and rearranging rooms to ensure proper spacing between people is no small task.

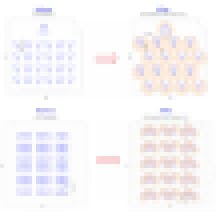

When school architecture firm STR took a stab at diagraming classrooms with about seven feet of space between students, they discovered that schools would likely need to cut class sizes by a third or more to accommodate the new layout. Under STR’s blueprints, classes of 24 students can host just 16 students. A packed cafeteria, which typically seats 215 students, would now accommodate just 45.

“People are so used to the intuitive desk and table spacing that we’re recommending our clients literally get colored duct tape and tape out the floor,” says Alan Armbrust, an architect and the executive manager at STR who helped with the plans. “It’s so unnatural.”

The limited cafeteria space may cause a particular headache for some schools. Perhaps a better solution is to convert a gym or another large space that can hold more students into an eating area, he adds.

Another pressing issue is the use of school lockers, which in some cases are stacked side by side, two rows high. “I think you have to abandon your lockers,” Armbrust says.

In areas with fair weather, schools can also shift instruction and recreational activities outdoors, as the added airflow dilutes the virus more efficiently, says Dr. Winslow.

Of course, that won’t work everywhere, adds Armbrust, who is based in Chicago. In fact, his reconfigured school plans were inspired by the fact that schools in his region will need to maximize indoor space for much of the year.

As for moving classes outdoors in the Midwest? “We could certainly do it at the start of school. We could do it at the end of school, but we’re really out of luck in the middle,” he says. “Arizona, California, you guys have more arrows in your quiver than we do.”