The closures of schools and daycare centers this spring abruptly changed life for many American parents. As almost half of those with young kids lost child care, their stress levels soared.

And their children suddenly started spending much more time watching media on screens.

A new study aims to make sense of these phenomena and draw fresh conclusions about what it really means when kids spend hours looking at cell phones, computers or televisions.

The early findings suggest that children’s “screen time” reflects parents’ stress levels and access to resources, not their philosophy or knowledge about child rearing.

“Screen time is a symptom of a family in distress,” says Joshua Hartshorne, co-author of the study and assistant professor of psychology and neuroscience at Boston College. “That’s what the COVID data seems consistent with. Take a whole bunch of parents. Take away their child care. Stress goes up and screen time goes up.”

The definition and consequences of screen time are up for debate, although concerns about it are not new. The amount of time kids spend in front of screens has stirred up anxiety at least as far back as when televisions became popular in the 1950s. Recent research and discourse has shied away from absolutes and has tried to tease out nuances about what media children are consuming and whether they’re watching alone or while interacting with their guardians.

“What matters is, what is the content on the screen and the context of the watching and the playing and what are the needs of the child?” says Lisa Guernsey, director of the teaching, learning and tech program at New America and author of the books “Screen Time” and “Tap, Click, Read: Growing Readers in a World of Screens.” “All three may be very different for every family in every household.”

Screen time has been associated with worse child developmental outcomes, but it can be difficult to discern exactly why. The kids who spend more time in front of screens also tend to be those whose families experience poverty, or racism, or inadequate social support—conditions that also correlate with worse outcomes.

Determining whether it’s screen time or low socio-economic status and the stress it causes parents (or some other factor) that is responsible for those outcomes would require randomly assigning kids to watch hours of TV and studying the results, Hartshorne says—not an experiment in which many parents want to participate.

But the pandemic offered up a natural experiment by drastically changing conditions for all kinds of families all across the country at the same time. Realizing this, Hartshorne and other researchers at Boston College and the University of Maryland who collaborate on the KidTalk study of child language development dug into data about school shutdowns, parent stress and user rates of streaming media services.

Their findings show that use of child-related media content spiked this spring, with increases that correspond with school closures. Viewership jumped right before schools officially closed in March and also in early June, at the end of the (remote) school year, according to data from Reelgood, a tool that aggregates streaming media services such as Netflix.

Such a large shift in family behavior did not come because millions of parents suddenly “changed their minds about the dangers of screen time,” the study says. Rather, it concludes that the change was spurred by a broad loss of child care and the additional stress that loss put on parents.

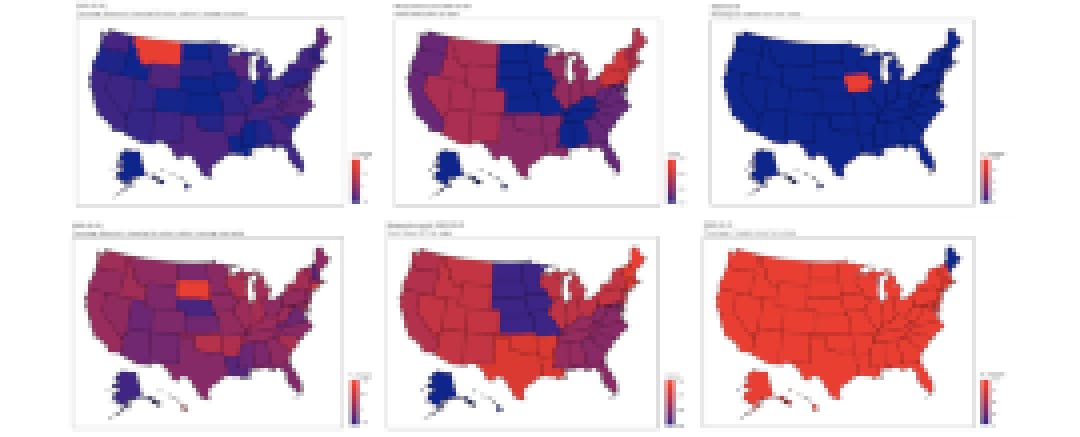

For each variable being measured, blue indicates lower levels, while red indicates higher levels.

Courtesy of Joshua Hartshorne.

Several national surveys about parent mental health as well as information gathered through the KidTalk program show parents who lost child care reported that their kids’ screen time increased more than parents who didn’t lose child care.

These results have not yet been peer reviewed and published by a scientific journal, but are available through a pre-print server in order to get feedback from the research community.

If these conclusions hold up, they may yield a couple of important insights, Hartshorne says. One is that trying to reduce screen time by coaching (or scolding) parents—currently a popular approach—might not do much other than make people feel guilty.

“This does help to advance the conversation so it’s not just about parental preference or whether parents are ignoring science or the advice of health experts,” says Guernsey, who was not involved with the study. “This is parents feeling like they have no choice but to use screen media, TV shows and games to help raise their children right now.”

And for some families, it's not just "right now." Even before the pandemic, low-income parents who lacked child care resources were “put in an almost impossible situation,” Guernsey says. “You’re put at a real disadvantage to do what science says you should be doing with your children.”

Another insight from the findings is that, as the study title suggests, child screen time levels could be used “as an index of family distress,” perhaps even a piece of information that could help diagnose whether a family or a community of families needs more resources.

Alleviating that distress may require policy solutions, Hartshorne says: “If what you really care about is screen time, what you should do is universal day care.”