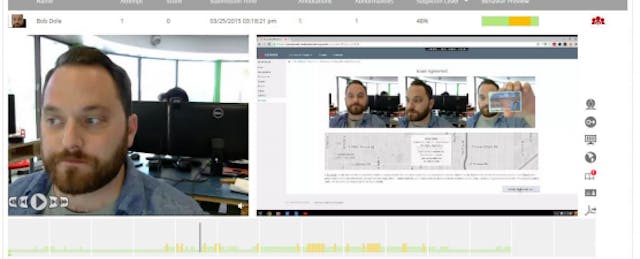

The pandemic has led to a spike in the use of automated proctoring software, which is designed to curb cheating on online quizzes and exams by recording students via their webcams and flagging suspicious activity. Increasingly, students encounter these proctoring tools in courseware required for their classes, thanks to partnerships between textbook publishers and proctoring companies.

The practice has stirred controversy, and this week a group of parents became the latest to push back against remote proctoring software. More than 2,000 parents signed a letter to one of the largest textbook publishers, McGraw-Hill, calling on it to end its partnership with Proctorio, calling its software “invasive and racially biased.”

Leaders of the parents’ petition say that automated proctoring tools are using textbooks as a kind of side door into higher education without having to be reviewed by college technology officials.

“It’s being done in a way that’s broader and more rapid without sufficient review by these institutions about doing it this way,” said Lia Holland, an activist for the nonprofit digital rights group Fight for the Future, which helped organize the letter-writing effort, in an interview with EdSurge. “These sorts of stalkerware and spyware technology do not have a place in higher education.”

“We view this as a human rights violation,” she added. “It violates the rights of these students to have privacy.”

In its release, the group cites an article from EdSurge that notes that as the result of a partnership announced in February between McGraw-Hill and Proctorio, some students now encounter automated proctoring as they work through routine assessments in the publisher’s Connect series of courseware.

Earlier this year, Luz Elena Anaya Chong, a student at Texas State University, told the EdSurge Podcast that the weekly quiz for her marketing class used Proctorio to record video of her during the test and notify her professor if she did something the system found suspicious. “It is very nerve-wracking. I don’t want to be accused of cheating when that was not even the case,” says Chong. “It makes me more nervous.”

The petition this week from parents also argues that automated proctoring tools have been reported to have more difficulty identifying students of color than white students, leading to instances where some students had to make special arrangements to take tests because the tools failed to work properly.

“The thing that makes us most concerned is the huge gaps in inclusion and the major bias against diverse students that these proctoring apps have,” said Holland. She said McGraw-Hill has invested in diversity and inclusion efforts lately, which made the partnership with the automated proctoring company “hypocritical and distasteful.”

Tyler Reed, a spokesperson for McGraw-Hill, said in a statement to EdSurge Thursday that “we take parents’ concerns and student privacy very seriously. We’re reviewing the letter internally.”

Officials from Proctorio could not be reached for comment this week. Proctorio’s CEO, Mike Olsen, told EdSurge in a previous interview that he considers remote proctoring to be a less invasive approach than having a human remotely proctor a test, as many other companies do.

Earlier this month a group of Democratic U.S. Senators sent letters to three proctoring companies, including Proctorio, asking questions about the technologies they use to monitor users, how they ensure accuracy and what steps they take to protect students’ privacy.

And this month the nonprofit Electronic Privacy Information Center filed a complaint with the DC Attorney General’s office against Proctorio and four other remote proctoring companies, alleging that the tools violate student privacy.