A most disruptive year to schools and society proved lucrative for the education industry, particularly for those raising private capital.

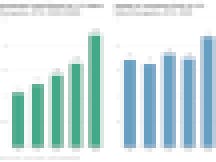

In 2020, U.S. education technology startups raised over $2.2 billion in venture and private equity capital across 130 deals, according to the EdSurge edtech funding database. That’s a nearly 30 percent increase from the $1.7 billion invested in 2019, which was spread across 105 deals.

The $2.2 billion marks the highest investment total in a single year for the U.S. edtech industry.

Many education entrepreneurs have long mused about how new technologies would usher in a “disruption” of the education market. But nothing proved to be as literally disruptive as a pandemic that closed schools, upended livelihoods and forced millions of students and educators to rely on new digital tools, many for the first time. From Zoom schooling to workforce reskilling, existing and new education funders jumped on opportunities to support products that not only serve as stopgaps, but also reimagine education for the long haul.

While big numbers are generally welcome by financiers, some investors offered a more measured reaction. “Edtech investing exploded in 2020. Unfortunately, it was on the back of the education system breaking down, especially at the K-12 level,” says Ebony Brown, a principal at Rethink Education, an education technology investment firm.

The pandemic has changed how generalist tech funds, which historically deployed capital elsewhere, viewed the education market, adds Brown. Leading some of the biggest U.S. edtech deals were blueblood firms, like Andreessen Horowitz and General Catalyst, along with new funds betting on education startups for the first time.

“For many parents who were serving as tutors and teachers for their children, it helped create a lot of empathy for solution providers. And investors saw in that market opportunities,” says Brown.

In the big picture, the surge of capital in the edtech industry is not an anomaly. A report from CB Insights showed that investments for all venture-backed U.S. companies reached a record $130 billion in 2020, or up 14 percent from 2019.

In this annual analysis, EdSurge counts all publicly disclosed investments in private U.S. edtech companies that support educators and learners across preK-12, postsecondary and workforce education. Not included are funding received as part of participating in startup accelerator programs (which are later accounted for as companies raise investment rounds after they graduate) and companies that primarily offer financial and loan services that serve education as one of many markets.

What’s the Big Deal?

Seven of the 10 largest investments went to U.S. edtech companies selling their services directly to consumers. The biggest deal, at $150 million, went to Roblox, primarily a consumer online gaming platform for kids but which has a growing educational component with resources that teach kids to code and design their own games.

Roblox is followed by Coursera and CampusLogic, which respectively offer online courses and financial management tools to colleges and universities. Handshake, which connects college students with employers, rounds out the trio of edtech companies on the list that sell to educational institutions (all in higher education).

Nontraditional alternative education providers Udacity and Lambda School also made the list, reflecting a growing appetite among investors for programs that focus solely on helping students acquire job-specific skills.

“Traditional higher education is very important, but it alone is insufficient for career advancement,” says Ashley Bittner, a co-founder of Firework Ventures, which invests in the workforce training sector. “I’m excited for alternative pathways that allow people to choose what paths work for them to build the kind of career and life that they want.”

These pathways may be in greater demand now. Even before the pandemic, analysts from the likes of Bain and McKinsey were forecasting dramatic shifts in the labor market; some 40 percent of jobs in occupations most likely to be automated could disappear by 2030. COVID-19 has only accelerated job displacement, impacting women disproportionately.

“Given the changing economy, we see a real opportunity to support companies that are training people in soft and technical skills,” says Bittner. “Our traditional education system is strained, and we do think that corporations will take on more of that role. They need to do it to stay competitive.”

Some companies are working with colleges to offer job-specific tech training programs that they normally don’t offer, including TRANSFR, which offers VR-based training and has worked with Alabama’s community colleges to prepare students for jobs at Lockheed Martin. Others, like Adjacent Academies, bring tech programs to liberal arts schools. Bittner is bullish on these partnerships that aim to help “traditional institutions adapt to the changing needs of the labor market and stay relevant.”

K-12: A Tale of Two Markets?

Notably absent from the list of biggest deals are edtech companies that primarily sell to K-12 schools.

“From a venture perspective, the K-12 institutional market was certainly not the most attractive. What were already tight [school] budgets shrunk even more due to the pandemic,” says Brown.

Following school closures, where technology was concerned, school leaders focused less on buying specific apps and software, and more on acquiring laptops and internet access for their communities. (Some orders were backlogged for months.) Providing other basic life necessities, like food, also took precedence. “District leaders were focused more on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs,” observes Brown.

Plenty of companies did raise capital to reach K-12 teachers and students where they were: in their own homes. School closures led to a rise in spending for supplemental educational services, and investment capital followed. Outschool, which offers an online marketplace of live classes for kids, raised $45 million. Juni Learning, a similar service, secured $10.5 million. These companies offer private classes, often taught by public school teachers who can make just as much, if not more, on those platforms than at their day jobs.

Also attracting capital were new, “parent-driven, next-gen school models” like Sora Schools and other services that support private homeschooling pods, observes James Kim, a principal at Reach Capital.

With most districts offering a subpar remote learning experience, such services have seen growing demand—at least from those who can afford them. But they could widen existing inequities as private educational services continue to attract students and teachers. “We are concerned about “gap-widening” behavior,” says Kim.

That sentiment is shared by his colleague and Reach Capital co-founder Jennifer Carolan, who wrote in a recent EdSurge op-ed: “We now face the risk of a parallel system—learning outside of our schools and learning inside of our schools. And we all know that when a public good is split, the most vulnerable will suffer.”

“It’s a natural response for parents to do all they can for their children. But the equity gaps are growing. When students return to school, the aftermath of this will be something that we’ll have to reckon with,” says Brown, of Rethink Education. She predicts there will be an increased demand for academic intervention programs and services to help students catch back up to speed.

Despite budgetary pressures, the K-12 institutional market still remains a focus for older education investors like Reach, which has been around for nearly a decade. “This is the spark that got districts to adopt digital products on a mass scale,” says Kim. “The question is: ‘Will they stay around?’ Our bet is yes.” He points to government relief funding earmarked specifically for programs to address learning loss as an important stimulus for the K-12 market.

It Pays to Be Known

Brand recognition goes a long way when it comes to attracting capital from existing and new investors. Just ask Duolingo and Udemy, which each closed a pair of investment rounds in 2020.

Former edtech entrepreneurs who returned for another stint were also greeted with big checks. Michael Chasen, the co-founder of learning management system Blackboard, raised $16 million for a new startup, ClassEDU, that is building classroom management tools on Zoom. Engageli, a similar effort led by the husband of Coursera co-founder Daphne Koller (who is an advisor), raised $14.5 million. Both amounts are outsized, especially for seed rounds, which averaged $2.7 million in 2020.

Deal sizes for private companies are rising across all industries, according to research from Cooley, a law firm that advises on transactions. Valuations are growing too, which is usually a signal that experienced investors watch warily. “I do feel like we’re in a bit of a bubble in terms of a fundraising environment,” says Kim.

Driving up edtech valuations are investors who are gravitating toward businesses that sell directly to consumers, a model that (theoretically) addresses a bigger market than selling to schools. Often, Kim adds, “I’m getting pinged by generalist investors who want a crash course in Consumer Edtech 101.”

Valuations by nature are optimistic projections, but they should not outpace reality. In a frothy market, Kim says Reach Capital has passed on a couple deals because it could not justify competing on valuation with other investors.

Where the Money Goes

The shift to remote work has been accompanied by companies and employees relocating to regions outside of tech hubs. But venture capital has not followed yet—at least for the edtech industry. Companies based in the San Francisco Bay Area accounted for nearly $1.2 billion raised, or more than half of all investment capital by edtech companies across the country. The New York area is second, totaling $307 million raised.

These coastal regions also account for the largest fundraising rounds. But there are exceptions. CampusLogic, a Phoenix-based provider of financial aid management tools for colleges, raised $120 million in July. Some of the highest valued companies can be found inland, too. Duolingo, the Pittsburgh-based language learning app developer, raised two rounds totalling $40 million on its way to a $2.4 billion valuation.

While the $2.2 billion raised by U.S. edtech companies set a record for the industry, the figure pales in comparison to their peers in Asia, home to “decacorns” like Byju’s and companies like Zuoyebang that raise over a billion dollars in a single round.

A report from education market research firm HolonIQ tallied over $16 billion of venture capital raised by education companies across the world in 2020, with China and India accounting for over 77 percent of that total.