The University of Maryland Global Campus has a decades-long history of educating working adults and members of the military, first by sending instructors to teach soldiers overseas and now through online programs and open educational resources. The public institution recently welcomed a new president, Gregory Fowler, who brings to the role experience as a scholar of English and as an administrator at Western Governors University, Hesser College and, most recently, online powerhouse Southern New Hampshire University.

EdSurge spoke with Fowler a few weeks into his tenure about the students he hopes to serve, his perspective on pandemic-era higher education and what kind of innovation he thinks is needed to help adults meet their academic and career goals. This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

EdSurge: What attracted you to this opportunity right now?

Gregory Fowler: One of the joys of the work here is, of course, they are in that line of innovative thinking and trying to think about how to serve their students best wherever they may be in the world. When I came in a couple of weeks ago for just a conversation, they showed me this video of the work that had been going on for decades of faculty members traveling around the world to basically meet students where they were.

And even though they were physically traveling, a lot of the work that they were doing is very much in line with where I've seen my passion, which is how do we—whether it is geographically or digitally or through academic support—meet students where they are and find out how to help them to succeed?

So that mission, that connection to that work, is really one of the things that really made me feel like this is a great opportunity.

Who are those students you currently serve? Who would you like to serve going forward?

The mission here is, first of all and foremost, to be open access for within the state of Maryland. And of course, we've also got the background of the work we've been doing with the military for decades.

A lot of it is trying to figure out how to help as many of those students—who are generally nontraditional, but not always—and certainly students who may have not been successful in other places—how might we think differently and approach them in a different way, or support them in a different way, that would allow them to be successful?

So we're certainly thinking about everything from microcredentials, partnerships with businesses, to other groups that may be trying to think about, How do we upskill all of our learners in different ways to get the skills they're going to need? The world of higher education and learning experiences is changing very quickly, and [so are] the skills that people are just going to need in the workforce. So how do we think differently about that? How do we create an agile organization that helps those students who may not be thinking about four-year degrees, two-year degrees or even sometimes graduate degrees but will still need new skills?

This is of course a difficult time in higher education, and a hard time to start a new leadership position. But on the other hand, you're at a place that has expertise in online education. What’s your perspective on this moment?

This [pandemic] has changed the way a lot of people look at online education.

Right now within the industry, there are all types of technology changes that are going on behind the scenes, and we need to be aware of those and doing what we can to leverage those and figure out how they might help more students be successful.

Two years ago, even a year ago, people might not have known what a Zoom call was. But Zoom has now become a household word. And of course, Zoom is clunky sometimes. It's a new technology. You got a whole lot of people who are trying to figure it out. The example that I think it compares best with is in the early days of MP3 players, when you were downloading music from various places, the quality of the music wasn't necessarily great but you knew that behind the scenes it was going to be getting better, and over time you ended up with MP4, and now you've got streaming services that have very high-quality music. Behind the scenes in higher education, you've got all of these various technologies and practices that are becoming more mainstream, and as a result, people are thinking differently about all types of learning experiences. That's going to play a big role in what online education looks like moving forward.

I do want to also point out that this big conversation about online versus remote learning continues to be important. I do not want to conflate what we are doing as a risk-mitigation strategy with what people have been doing for decades to make online education deliberate, intentional, complex, but also serving students who have particular types of needs.

One of the things that I will be curious to see how it happens is how more traditional institutions begin to adopt some of those technologies and policies and practices as part of their sort of normal, daily, day-to-day operations.

In the meantime, the online space, we'll be trying to think more and more about, How do we take this level and reach what's going to come next? How do we go from the iPhone 1 to the iPhone 12 or 13? What will be that new technology?

How does your background as an English scholar relate to the work that you do now, and how does it inform the innovation that you're interested in in your new role?

It’s funny, that comes up a lot. But I will also point out that my former boss and mentor Paul LeBlanc was also an English major. And ironically, a lot of people who are in the field are often English majors. So I'm always saying, what do you mean? We're everywhere!

Some of my favorite authors have taught me a lot about thinking outside of the box about human nature. … That's very, very much tied to exactly what we were trying to do in higher education. That is, understand different ways of looking at the world—different experiences—and bring to bear the technologies and tools that those people from various types of experiences need to be successful.

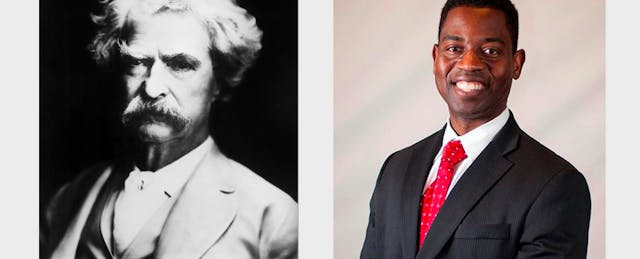

All of my favorite writers—from Shakespeare to Richard Wright to Mark Twain to so many others—are people who have really dived into looking at the world and challenging the status quo. Whether they do it through humor, like Mark Twain sometimes does, or they do it through drama, as Shakespeare does, or whether they do it through some very powerful writings, like Richard Wright—all of them do that.

Humanities as a whole, it's all about what does it mean to be human—both what we create and how we create. It in a lot of ways is very much tied to exactly what we're trying to do.

You’re at a nonprofit institution that serves “nontraditional” students. How do you think about competition with for-profit institutions for those students?

In talking to a lot of my colleagues, even in that space, they have taught the industry a lot about an approach that is much more student-centric and learner-centric that might not necessarily have been the way we approached it some time ago.

You used the word competition. It is true there's a certain level of competition to this, but I also go back to: There are 30 million Americans who have some college and no degree. There are a whole lot, I think almost an equal number, of Americans who have no degree who are looking for skill sets that go beyond what they would need to have in high school. None of us are going to get all of them. None of us, when you take a look at the numbers, have even 1 percent of them as a group right now.

I think the first thing we can do is make sure we keep in mind what our missions are. ... Even within the [Maryland] system, you've got research institutions, you've got HBCUS, and if we were trying to do everything for everyone, then it would be truly a free-for-all. Our job in this is to really think about those students who need an open-access institution and how they might be successful in that.

A lot of the work that we're doing is trying to be collaborative right now, in part because there are so many things out there that we just don't know. And being able to have that type of collaboration has been more beneficial than a truly competitive market. … I don't want to dismiss the idea of competition because that is real, but I also want to make sure, at least at this point in the industry, [that] it feels like there are enough people trying to figure out how to do this [in a way] that is more collaborative than competitive.

In your experience, what is great higher education for adults?

They aren't looking for the coming-of-age, rite-of-passage experience that you would find in SNHU in New England, where you've got 4,000 students who are 18 years old coming on a New England campus and living in dorms.

I think that the future of higher ed has to be far more transparent about and accountable to—I use this term a lot—KSADs: knowledge, skills, abilities and dispositions. We have to be much more explicit about what those are and how we help people acquire them. Because as you know, there has been this big conversation in higher ed and certainly the larger public about what is the value of college? And if we're going to pay for these things, what are we actually getting for it?

For a long period in our history, higher ed has been this sort of black box experience, where people do it because they feel like they have to do it, but they aren't quite sure what they're supposed to get out of it other than the degree at the end of it. And what you're finding, particularly with higher ed and adults, is they're asking for more.

I think we have to be clear about, if you come here, we want to understand what you're trying to accomplish and what are the skills that are going to be necessary in that field. So you're trying to move from accounting, into finance. What are the skills that you need to have? … I think adults do want that sort of explicitness about how you're going to get me there. How long is it going to take, how much is it going to cost? And at the end of this, can I clearly explain to other people what those things were?

I move away from this idea of a buffet-style general education approach, where you take two of the humanities, take two of the social sciences, you take two of the quantitative, and something magical will happen at the end of all of that. …

A lot of the things that we do will be replaced by computers and technology that can do it better. They can never replace the human element and the critical thinking [and] the effective communication skills. … We want to prepare you in a way that no matter what technology comes along, you can actually be a colleague in that work and have the skills you're going to need. That's what I think the new “gen ed” would be.